The People Will Save the Planet, Not the Courts

The European Court of Human Rights has condemned Switzerland for its climate policy. It’s a dangerous overreach.

Thousands of our readers financially support Persuasion. That support is what allows us to staff our team, pay our authors, and keep our content free for everyone in keeping with our nonprofit mission. But we need to raise our revenue to keep paying the bills.

If you’re able to become a paying member today, we’d be grateful for the support. Or, if a one-time contribution is easier, you can donate using this link.

With thanks,

Yascha and the Persuasion team

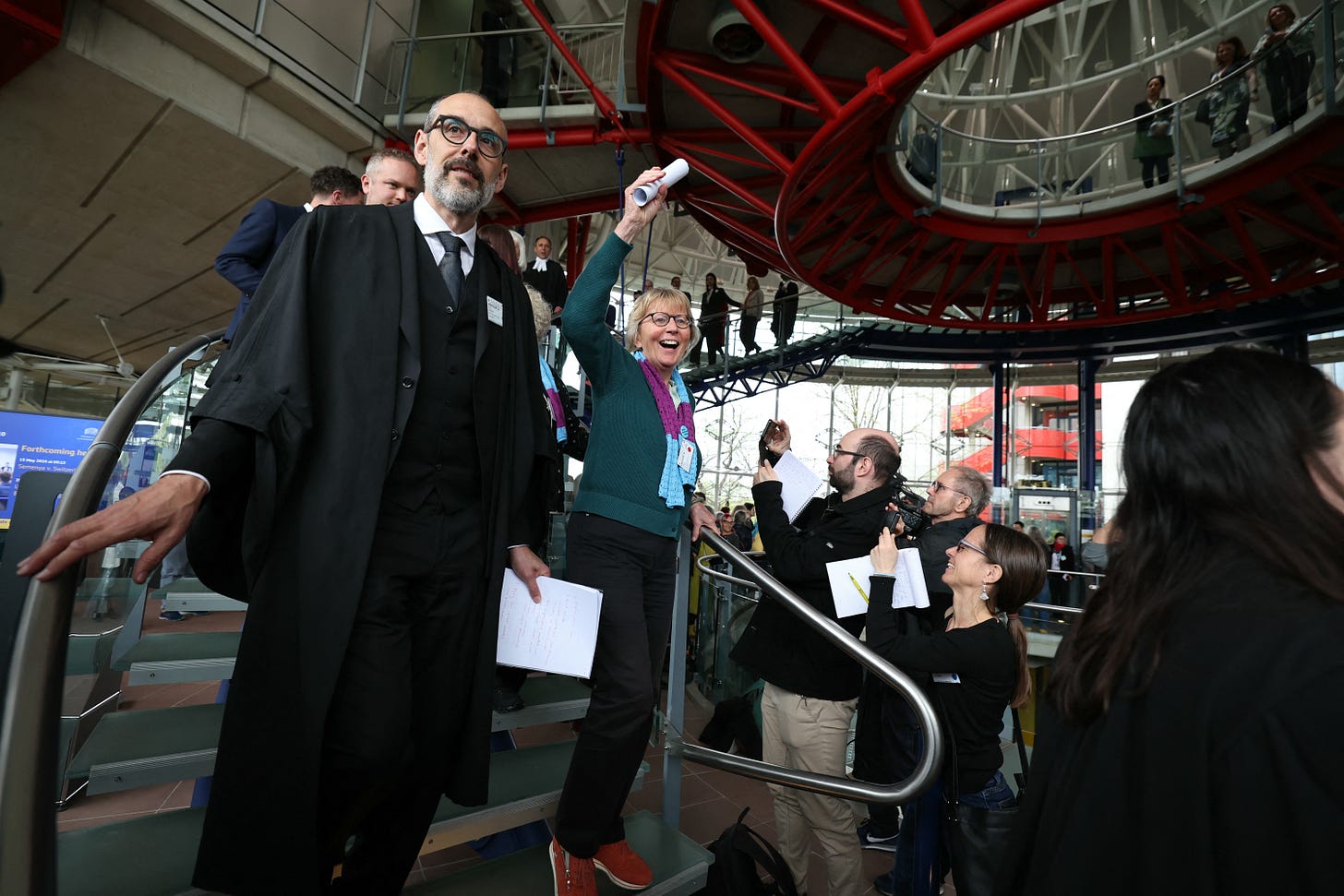

On April 9, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) published a landmark decision condemning Switzerland for its climate inaction. The court in Strasbourg ruled that Switzerland’s insufficient efforts to reduce its national greenhouse gas emissions violated the human rights of over 2,000 older Swiss women.

The stakes of climate policy are very high, and the rule of law and a strong judiciary are key ingredients for a healthy liberal democracy. We know all about the dangers of pure majoritarianism, where the will of voters is left unchecked.

But it seems that we have now overcorrected by letting courts shape public policy directly. The ECtHR decision is a dangerous overreach into a matter that should, first and foremost, be in the hands of the electorate and their representatives.

The 18th century French philosopher Montesquieu argued that judges should be the “mouth of the law”—that is, they should stick to the law as it is written. Judges are unelected, and they draw the legitimacy of their decisions from laws and constitutions voted for by the people and their representatives. There is of course room for courts to act on climate policy, and they regularly do. But this must be based on laws and constitutional amendments previously approved by parliaments. In the case of the ECtHR, we are witnessing a mission creep without direct textual backing.

So let us look at the logic of the Strasbourg Court. The ECtHR found that in the Swiss case there had been a violation of Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights. You would be forgiven for assuming that said article is about climate policy. Instead, the article states that “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.” Drawing on this, the Court argues that senior citizens are most impacted by climate change, especially heatwaves, and have had their lives upended as a result. (Never mind that since 1990 the annual probability of dying among 80+ Swiss women has halved.)

There are several problems with this reasoning. The link with the climate seems at best extremely tenuous, and would have likely been laughed out by the original signatories of the Convention. One should keep in mind that the Convention was explicitly set up to defend individual rights, whereas the decision pushes policy change on de facto common good grounds. One may of course argue that common goods are important—including the good that comes from living in a world without climate change. But the fact remains that this is not what the Convention was written for.

In fact, the ECtHR decision reflects a growing aristocratic temptation within democracies to side-step the tricky and messy process of electoral democracy by putting policy as far away from the electorate as possible and into the hands of experts. Its reasoning derives from the idea that legal documents are “living instruments” that need to be reinterpreted by judges to reflect changing times.

But the ECtHR draws its legitimacy from the Convention, ratified by the national parliaments of the members of the Council of Europe. Pushing the living instrument doctrine too far weakens this legitimacy at a time when some countries ignore its decisions while others are debating leaving it. The temptation to continuously tighten the policy scope of electoral democracy risks encouraging authoritarian voices on the political fringes who want a strongman to ignore parliaments or courts altogether.

The Swiss case provides a nearly perfect case study of the clash between non-elected bodies and the will of the electorate. Jessica Simor KC—a British lawyer instructed to represent the Swiss women—noted this tension explicitly: “This is something that comes up all the time, the conflict between this idea of democracy as just what the people choose, and democracy as entailing fundamental and universal rights which matter irrespective of what the majority decides.”

But the Swiss model actually shows that the people can be trusted to grapple with complex bills. The Swiss take climate policy seriously, as they have voted in not one but two referenda on the topic in the last three years, in 2021 and 2023.

The first climate bill—which aimed for net zero emissions by 2050 and included a car fuel levy as well as a tax on air tickets—was narrowly rejected by the electorate in 2021, with many citizens worried they would have to foot the bill for net zero policies.

Rather than pouting and name-calling the Swiss electorate, the Swiss parliament went back to the drawing board and put forward a new bill that still aimed for net zero emissions by 2050, but this time without any new taxes or bans, preferring instead various incentives. This new bill, which puts Switzerland on track with the pledges it took under the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, was overwhelmingly approved by the Swiss last summer.

Switzerland, with its many referenda, is a strange and idiosyncratic political model, but it serves as a reminder to environmentally-concerned lawmakers and activists across the world that when treated like adults, the electorate can seriously grapple with important policy matters.

As for the ECtHR, it risks severely damaging its reputation and the strong ideals that the European Convention of Human Rights stands for. The lone dissident ECtHR judge, Tim Eicke KC, expresses this fear best: “While I understand and share the very real sense of and need for urgency in relation to the fight against anthropogenic climate change, I fear that in this judgment the majority has gone beyond what it is legitimate and permissible for this Court to do and, unfortunately, in doing so, may well have achieved exactly the opposite effect to what was intended.”

François Valentin is a Senior Researcher at the Westminster-based think-tank Onward and the host of the Uncommon Decency Podcast on European affairs.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

This contribution of Mr. Valentin is very intelligent und very smart … but as a Swiss citizen I must ask myself (and you, Mr. Valentin) if you really know politics of Switzerland (and tactics of bourgeois political partys, especially the right wing swiss peoples party SVP). In a political discussion on TV two days after the decision of the ECtHR the two representatives of bourgeois partys argued quite the same manner like Mr. Valentin - but meaning that every thing in Switzerland is oK (including climate problems) and that Switzerland is doing its best and NATURALLY that no „foreign“ court has the right to decide over Swiss climate policies. Two other politicians from green liberal and socialdemocratic parties said: We have to admit that Switzerland is doing much to less to achieve the goals oft the 2050-Paris-treaty which was signed also by Switzerland. As I understood the ECtHR did NOT interfere in Swiss politics. So - unfortunately - your contribution, Mr. Valentin, may have a certain intellectual value, but climate change needs action, not intellectual doddles. Sorry to say that (because I usualy like the contribuations of PERSUASION very much!).

If I know any country on Earth that doesn't mind telling anybody where the dog died, it's Switzerland. The honorable judges better fasten their seatbelts if they have any enforcement actions in mind: it's going to be a bumpy ride.