The Problem with “Decolonizing” Global Health

The movement's radical fringe could undermine key principles in the field and make it harder to fight global scourges like malaria.

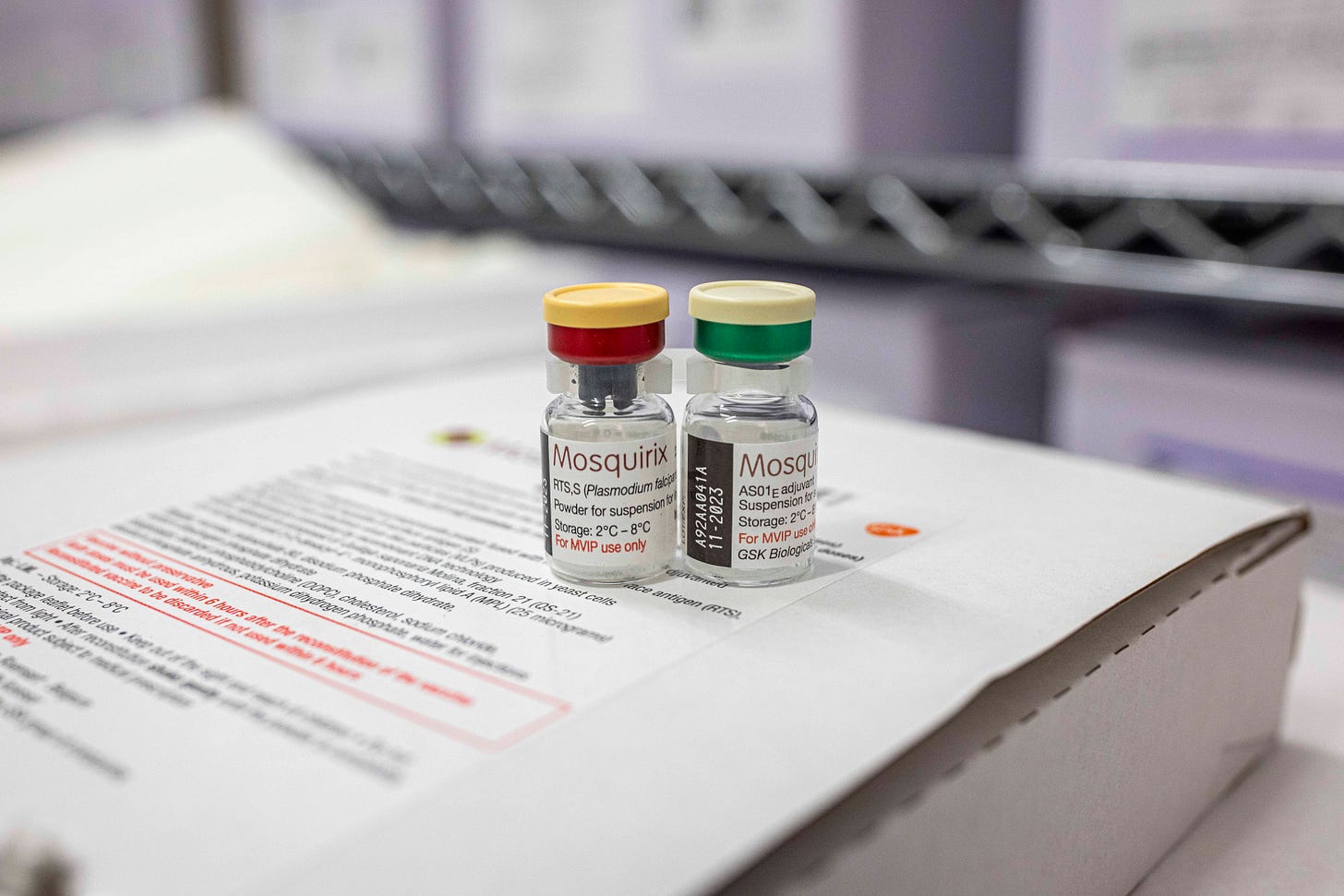

Last year, the World Health Organization made the historic decision to recommend the first malaria vaccine for use in regions with significant transmission of the disease. Earlier this month, scientists at the University of Oxford announced that they had developed another vaccine that is even more effective and could be “world-changing.” The continued development and use of the vaccine could save tens of thousands of lives every year and give millions of children in Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and South Asia the chance to grow up without the death and destruction that malaria causes.

The malaria vaccine is just one of the many achievements in global health since the mid-20th century. In the last sixty years, smallpox has been eradicated, polio has been nearly wiped out, significant advances have been made to prevent and control HIV/AIDS, and maternal and child mortality rates have dropped dramatically. Such advances are only possible when there is investment and trust in rigorous scientific processes, the benefits of which are extended to all people, irrespective of their race, ethnicity, or geographical origin.

But in the past few years, an academic and cultural movement calling to “decolonize global health” (DGH) has come to have the potential to undermine these core principles. While there is no single agreed-upon definition of DGH, the most extreme version argues that global health is a form of modern colonization, calls for an overhaul of the discipline, and seeks to limit “Western” influence on developing nations. Some advocates of this movement have gone so far as to call for the field of global health to be dismantled altogether. In doing so, and despite alleged good intentions, the radical edge of this movement may unwittingly threaten the right to health of some of the most vulnerable people in the world.

In the last few years, this issue has garnered significant attention—over 50 academic papers on the topic were published in 2020 alone, several grey literature reports circulated, and countless webinars and conferences were conducted. While criticism of global health is not new, this increasingly popular iteration is more radical than earlier versions of the critique and can be intolerant of discussion and constructive dissent.

The DGH critique rests on two main arguments, which can be evaluated independently.

The first asserts that global health has been designed to maintain established power asymmetries, since it is rooted in an extension of “Western knowledge” which, the argument goes, is inherently colonial in nature. According to this argument, global health’s emphasis on research-based evidence over “lived experience” is unjust and also serves to entrench power hierarchy.

This argument contradicts the widely accepted and long-standing scientific principles and social rules which emphatically hold that a claim must be judged on merit—independent of the status and identity of the person making the claim. Furthermore, there is nothing exclusively Western about reason, humanism, and the scientific method. Arguing that the scientific method is white and Western demeans researchers from other backgrounds and dismisses their contributions to modern science.

This assertion is also dangerous because when valid claims to scientific knowledge are denied, doubted, or dismissed based on identity, the door opens for political demagoguery and opportunism. Humanity has a long history of politicizing science with devastating consequences. For example, South African President Thabo Mbeki invoked anti-colonial sentiment to justify his denial of the viral causes of AIDS and the efficacy of antiretroviral drugs. While there is some validity to the claim that pharmaceutical companies were capitalizing on the illness of the people living in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Mbeki government’s opposition contributed to more than 330,000 people dying prematurely from HIV/AIDS over five years and at least 35,000 babies being born with preventable HIV infections. More recently, in an attempt to generate support for expedient but ineffective policies, some governments made similar anti-colonial claims as a way to undermine COVID-19 knowledge arising from high-income countries.

The second DGH argument frames global health as a Manichean struggle between groups of people that are broadly and vaguely defined. Generally, the DGH literature would have us believe that in global health today there is a “good” side (the oppressed) and a “bad” side (the oppressor), with some advocates going so far as to describe these groups as “morally unrelated.” In practice, DGH uses this framing to divide the world between groups like the “global north” versus the “global south,” “white people” versus “BIPOC people,” and “majority world” versus “minority world.”

But it is not at all clear that the underlying cause of global health inequities are exclusively, or even primarily, due to such historical and pervasive power systems. This is not a trivial mistake on the part of DGH proponents, because oversimplifying the multi-faceted causes of complex problems leads to misdiagnoses and ineffective solutions. This analysis can also lead to a sense of paralysis and nihilism, which we see when DGH experts call for the field to be dismantled to rid ourselves of these intractable historical origins.

The radical fringe of the DGH movement has the potential to undermine key principles in global health and deter future progress. By threatening the foundations of global health—knowledge, universalism, and purpose—it inadvertently advocates for cuts to overseas aid and development budgets and withdrawal from peace and state-building initiatives.

To be sure, the global health field is imperfect. Evolving from public health to tropical medicine and international health, the field worked to aid the advancement of colonialism and empire. Just like other areas of international cooperation, global health continues to face its own hurdles. For instance, the provision of essential health services by international organizations can undermine the legitimacy of national governments. Similarly, many donor-led programs are badly designed and poorly integrated with local health systems. These are problems that professionals in the field should recognize and seek to limit or avoid.

But “coloniality” is not the sole cause of these and other failures, as the DGH argument would claim. While the moral ground upon which DGH is premised may be honorable, any progress towards decentralizing authority and decision-making power requires a properly formulated diagnosis of the problem, an evidence-based theory of change, and a clear and feasible plan of action. Good intentions do not necessarily translate into beneficial outcomes. Ultimately, our potential to collectively build on the global health achievements of the past decades—and to fight global scourges like malaria—rests on our ability to uphold rigorous scientific standards while promoting universal human rights.

Trish Nayna Schwerdtle is a senior global public health researcher at the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health focusing on climate change and health. She is also a Heterodox Academy writing fellow.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

tI don't understand why the Global Health experts even need to say "the field worked to aid the advancement of colonialism and empire." So did the railroad system in India, but India would have been nuts to dismantle that system when it won independence instead of building on what was there. Even China under Mao wasn't defensive about saving the beautiful wharfs (like the Bund in Shanghai) and cultural artifacts (temples, the Great Wall, etc) by colonizers or hated feudal warlords. The Chinese recognized these cultural stand-outs wouldn't be there today without the hard labor of the Chinese underclasses. They built on their troubled past. I don't believe the people who play 'lived experience' against scientific discoveries are 'well--intentioned'. Many discoveries in science, art or manufacturing happened under regimes that the narrow-minded would hate. Don't not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Build on the past and weed out inequality instead of assuming colonialism is somehow baked into everything modern.

First of all, with the globalization of travel, there are very good reasons to ensure the health and safety of travelers/traders/business people to other countries, and to do that, it makes sense to extend those concerns to the citizens of those countries, and assist them with those health issues.

Continuing to delegate people into "oppressed" vs "oppressor" categories will only serve to generate ill feelings and hatred between those groups. It is one thing to act as a colonizer to exploit or enslave the local populace, it is quite another to offer help and solutions to serious problems in those populations.