It is, I suppose, a little random which cultural figures come to define your understanding of a country—especially if you grow up hundreds or thousands of miles away from it. It depends on what you encounter when you first visit that country, and on what shows or albums or comedians the first friends who serve as your guide to that terra incognita happen to love.

My sense of the United Kingdom is, for those kinds of random reasons, deeply shaped by the sitcoms most beloved by one of my closest college friends, Will. My understanding of the British class system was at some early stage shaped by Fawlty Towers, my sense of how Britain understands its own history by Blackadder, my sense of the basic workings of its political system by Yes, Minister. I have, I hope, somewhat expanded my sources of information and frames of reference about Britain since then—but at some foundational layer, ever-lurking, there will always be Basil Fawlty and Captain Blackadder and Sir Humphrey.

American culture was so ubiquitous when I was growing up in Germany that my most important touchstones about it are rather less distinctive. When I switched on the television, with its meagre three channels, after school—my mother was far too disdainful of TV to purchase cable, but far too busy to monitor how many hours I spent in front of “the box”—it was usually playing the Smurfs or Sesame Street, ALF or the Simpsons, The Cosby Show or Married with Children. Like just about any kid born in the West in the 1980s, I had deep fluency with American popular culture before I ever set foot in the United States.

That began to change on my first visit to America in 1994, when my mother was performing at the Spoleto music festival in Charleston, South Carolina. But my cultural memories from that first trip are limited to three things: I developed an all-consuming obsession with hash browns. When some colleague of my mother’s kindly offered to throw a pool party for my 12th birthday, my mother, not understanding the dimensions of new world foodstuffs, insisted we order one Domino’s pizza per child. And for some unlikely reason which now totally escapes me, Sandra Bullock dropped by that pool party.

So it was on my second visit to the United States, a couple of years later, that I first came into contact with a piece of comparatively obscure American culture which would go on to shape my sense of the country that has since become home. In my aunt’s living room in Morningside Heights, she and her friends were reminiscing about the late 1960s when, freshly expelled from Poland, they had first arrived in New York. Somebody put on a CD called “That Was the Year That Was” by Tom Lehrer, a singer-songwriter who died yesterday in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the age of 97.

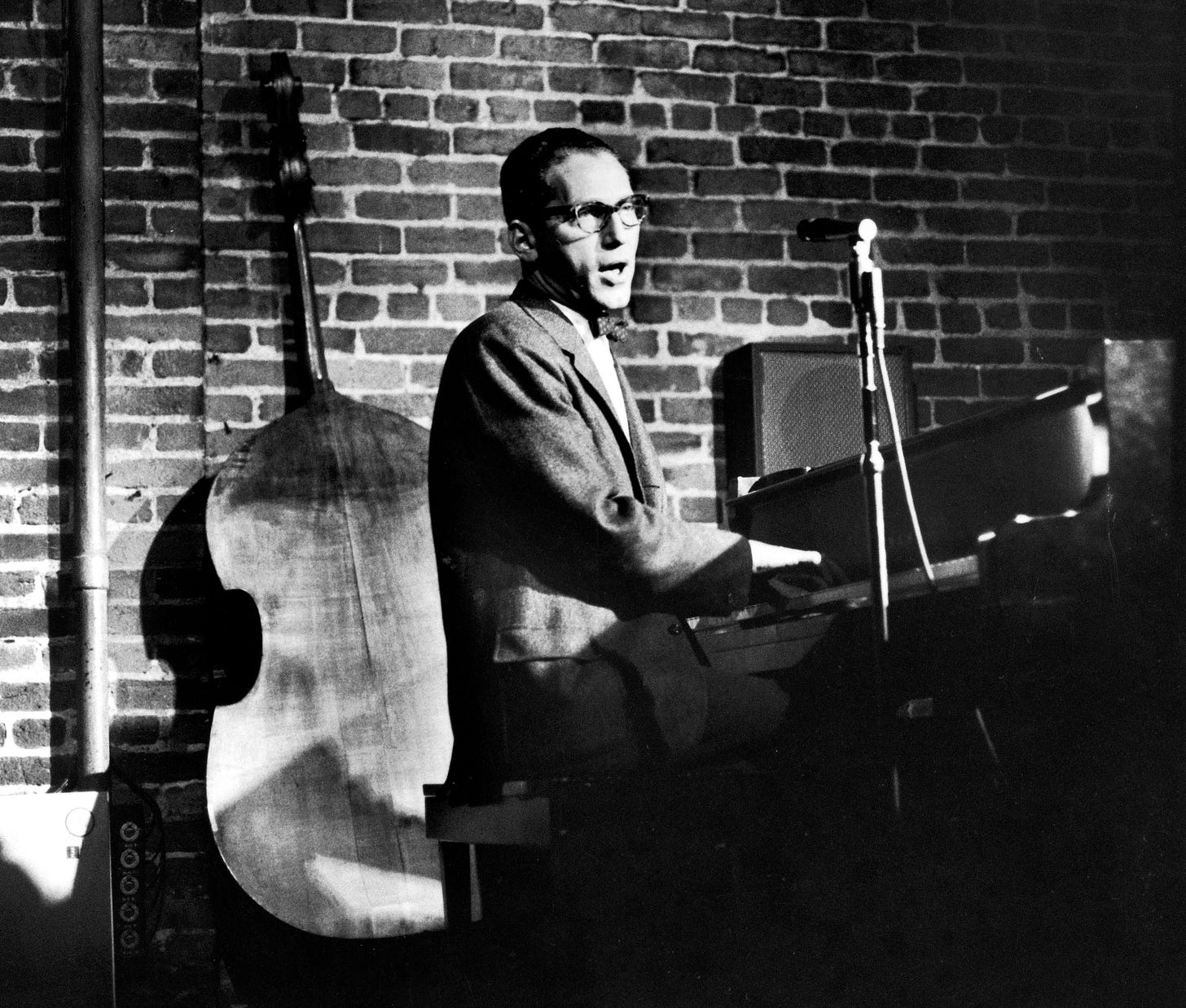

I had never before heard of Lehrer, could barely understand what words he was singing, and completely lacked the context to make sense of his many allusions to recent political events. The music was breezy and upbeat, the singer’s voice firm and friendly. But even as I struggled to fully appreciate the jokes, I could tell that they were laced with countercultural venom.

“I’m sure we all agree that we ought to love one another,” Tom Lehrer told the audience in the introduction to National Brotherhood Week, the first song on his album, “and I know that there are some people in the world who do not love their fellow human beings, and I HATE people like that.”

The song goes on:

All the Protestants hate the Catholics

and the Catholics hate the Protestants

and the Hindus hate the Moslems

and everybody hates the Jews.

But during National Brotherhood Week

It’s National Everyone Smile-at-One-Another-Hood Week

Be nice to people who are inferior to you

It’s only for a week, so have no fear

Be grateful that it doesn’t last all year!

I was spellbound.

When I listened to Lehrer’s album for the first time on that hot summer day in the mid-1990s, it was already thirty years old. Since then, another thirty years have passed. Some of the songs feel very much of that time, as when Lehrer pokes fun at the way in which the supposed necessities of the Cold War were seducing policymakers into ignoring the recent history of World War II.

Take his “lullaby” about a plan, later abandoned, to furnish “our current friends, like France, and our traditional friends, like Germany” with nuclear weapons:

Sleep baby sleep, in peace may you slumber

No danger lurks, your sleep to encumber

We’ve got the missiles, peace to determine

And one of the fingers on the button will be German.

[…]

Once all the Germans were warlike and mean

But that couldn’t happen again

We taught them a lesson in 1918

and they’ve hardly bothered us since then.

The poison dripped even more acidly in a song about Wernher von Braun. A member of the Nazi party, von Braun had played a key role in developing the rockets the Third Reich dropped over London during the Blitz. After World War II, he was brought to America, where he played a key role in the space race.

But Lehrer now insisted that we should let bygones be bygones:

Don’t say that he’s hypocritical

Say rather that he’s apolitical

“Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down?

That’s not my department,” says Wernher von Braun.

Some have hard words for this man of renown.

But some think our attitude should be one of gratitude.

Like the widows and cripples in Old London Town.

Who owe their large pensions to Wernher von Braun.

Some of Lehrer’s jokes speak to a particular historical moment. But others keep coming back to me decades later because of breaking news stories. When Kamala Harris was diagnosed with Covid, for example, the White House—which had until then at every turn been at pains to emphasize how strong her relationship with her boss in the “Biden-Harris administration” was—rushed to emphasize that Joe Biden was not a “close contact” of hers. My mind naturally went to Lehrer’s song about Hubert Humphrey, the vice president Lyndon Baines Johnson studiously ignored throughout their time in office:

Second fiddle’s a hard part, I know

When they don’t even give you a bow

The album also features Tom Lehrer skewering supposedly progressive educational fads which only succeed in making things unnecessarily confusing in “New Math”; him poking fun at America’s over-reliance on military might in “Send the Marines” (For might makes right, / And till they’ve seen the light, / They’ve got to be respected, / Till somebody we like can be elected); and him making light of fears about nuclear proliferation in “Who’s Next?” (Egypt’s gonna get one, too / Just to use on you know who. / So Israel’s getting tense, / Wants one in self-defense. / “The Lord’s our shepherd,” says the psalm, / “But just in case, we better get a bomb!”)

However, it is the plaintive song Lehrer wrote to commemorate World War III—in the recognition that, after the event, it would likely become impossible to do any such thing—which first came to my mind when, earlier today, I heard of his passing:

Little Johnny Jones

He was a U.S. pilot

And no shrinking violet

Was he, he was mighty proud

When World War III was declared

He wasn’t scared

No, siree!

And this is what he said on

His way to Armageddon:

So long, mom,

I’m off to drop the Bomb

So don’t wait up for me

But though I may roam

I’ll come back to my home

Although it may be

A pile of debris

[…]

I’ll look for you

When the war is over

An hour and a half from now!

So long, Tom.

For all of his fears about the future, he lived a charmed life. Born just too young to serve in World War II, he was educated at Horace Mann and Harvard University. It was when he was a graduate student in mathematics that he started performing a few songs around campus, and unexpectedly shot to national semi-stardom. His first album, self-published on an initial print run of 400 copies and only available by mail order, sold about half a million copies.

But in one sense, at least, Lehrer was decidedly of a different time: He had little interest in the limelight. Only during brief periods of his life did he perform publicly, or even write songs. And while his songs make clear his left-leaning political views, he could never quite get comfortable with the self-consciously politically engaged comedy which eventually took over big parts of American culture. Long before recent complaints about the rise of “clapter comedians,” he insisted that “my purpose was to make people laugh and not applaud. If the audience applauds, they’re just showing they agree with me.”

For the most part, Lehrer therefore focused on his work as a mathematician, which included stints teaching at leading universities like MIT and working at Los Alamos. In the last decades of his professional life, he was at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he split his teaching duties between the math department and the department of performance studies.

Lehrer was not a builder of legacies. His style of musical comedy has mostly died out. He does not appear to have been interested in family; asked whether he had ever married or had children, he quipped that he was “not guilty on both counts.” Nor did he ever aim to maximize the financial profit he would draw from his fame; a few years ago, he declared that all of his lyrics and melodies would henceforth be in the public domain (which is one reason why I’ve been able to quote so liberally from his songs.)

But, perhaps despite himself, Tom Lehrer did leave a lasting legacy: He deeply shaped the way I—and many others—see the country he skewered so lovingly in his unforgettable songs.