The Wild Waltz of Democracy

If Don Camillo and Peppone could figure out how to compromise, there’s hope for the Republican Party yet.

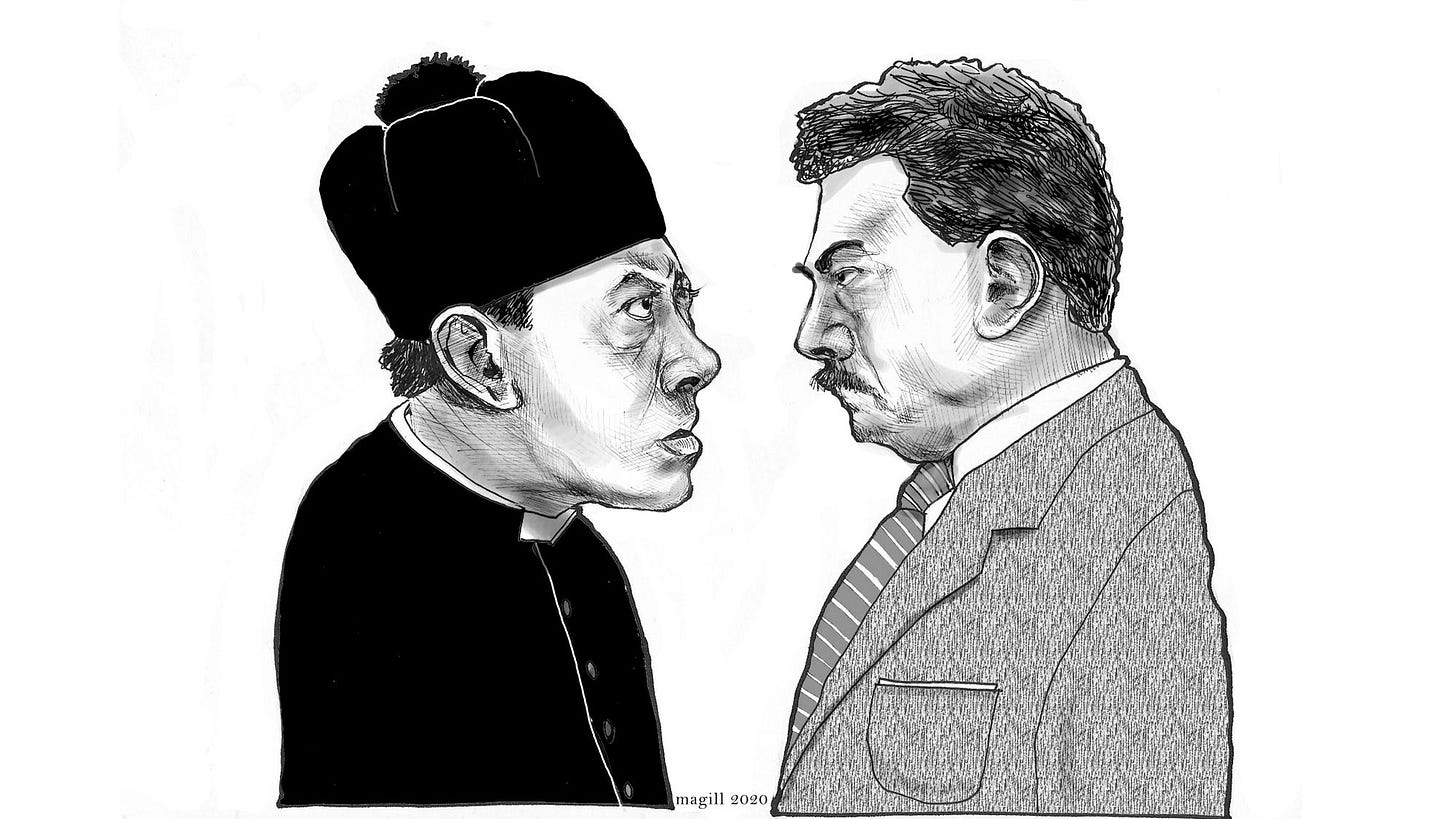

Do American children know about Don Camillo and Peppone? Probably not, so let me introduce you to my childhood heroes from a series of stories by Italian journalist Giovannino Guareschi. Don Camillo is the parish priest of Brescello, a village in the Po Valley in northern Italy. His friend and nemesis, Peppone, is the Communist mayor of the town. Both men have iron fists, both are totally irresponsible, and both are stubborn as mules. They are, naturally, official enemies, a state of affairs complicated by the fact that Don Camillo and Peppone like each other. In fact, they were partisans in World War II and fought the Germans side by side. But now, in postwar Italy, they inhabit different ideological worlds—no, different universes.

Peppone glorifies the Soviet Union and its Supreme Leader, which does not prevent him from being a devout Christian. He tries to have his newborn son baptized Lenin. Don Camillo refuses. Hilarity ensues.

But Don Camillo is no pacifist, either. Instead of loving his enemies he would like to beat them up—or open fire on them with the machine gun he keeps conveniently stored in his bell tower. Only sweet Jesus can talk him out of his worst instincts, which explains why Don Camillo has regular conversations with the crucifix that hangs on his church wall.

I devoured all the stories when I was young. Later I saw films of them, starring the French actor Fernandel—whose enormous teeth made him world-famous, or at least Europe-famous.

Little did I know about the grim reality lurking behind the funny stories. Which, of course, brings us to Greece.

The Greek Civil War has by now slipped our collective mind. It had its beginnings in 1944, then broke out in earnest in 1946 and lasted until 1949. The casus belli was the question of whether postwar Greece would become communist. During the Nazi occupation, communists and anti-communists had valiantly resisted the German occupation together. It was Greece, under the right-wing strongman Ioannis Metaxas, that scored the first military victory against an Axis power—Italy, in 1940.

The victory was short-lived: The Germans invaded Greece in 1941. And as soon as the Nazis were vanquished, the former comrades-in-arms turned on each other. Out of the country’s population of some 7.5 million, around 200,000 people died. A million Greeks were driven from their homes.

Both sides committed atrocities. Both sides tortured. Both sides slaughtered civilians.

The Greek communists were supported by Albania and Yugoslavia, the anti-communists by Great Britain—until 1947, when the British ran out of money, went to Washington, and humbly asked the Americans for support. The rest, dear reader, is history—the history of the Cold War. Let me put it this way: Greece was Korea before Korea was Korea, albeit with a slightly better outcome. In still simpler terms, Don Camillo and Peppone did not become farcical frenemies; instead, they brutally mutilated each other. No comedy here, only tragedy.

In the spring of 1948, the danger was real that Italy would go down the communist drain as well. Italy’s Communist Party was a power to be reckoned with—millions of members, grass roots activists in every city and region. The Communists were celebrated, rightly, as heroes of the anti-fascist resistance. They had just entered into a coalition with the Socialists.

The American government was in a state of high alarm, which was not hysterical but justified. Italy could have turned into a Soviet satellite or descended into civil war like the one in Greece. Instead, in the elections of 1948 the Christian Democrats (Don Camillo’s party) got 48 percent of the vote, their best result before or since. The “popular front” of Communists and Socialists got just 31 percent.

It was pure fear that brought about the 1948 election result—fear of dictatorship, fear of chaos.

Don Camillo’s party managed to hold onto power until 1980. It may have looked like stability. In fact, it was anything but. True, Italy’s first postwar prime minister, Alcide de Gaspreis, ruled for seven years; but after him, it was fairly crazy. Here is a partial list of his successors: Pella (154 days), Fanfani (23 days), Scelba (one year, 146 days), Segni (one year, 317 days), Zoli (one year, 43 days), Fanfani again (230 days) . . . you get the idea.

Italian governments were famously rickety, and Italian postwar politics were a wild dance. It was a dance around the Communist Party, which never broke down or went away and remained committed to erecting its dictatorship of the proletariat. In contrast, Don Camillo’s party was never able to rule on its own: The Christian Democrats depended on dance partners from the moderate left as well as the right. Conservatives and liberals were forced into one uneasy alliance after another.

After 1963, the dance was able to expand to cross the center of the political dance floor. The Socialists had broken with their Communist comrades over the unpleasantness in Hungary—Soviet tanks in Budapest—so the Socialists joined the dance card as partners in the wild waltz of Italian democracy.

By 1976, the transformation was complete. The Italian Communists had turned themselves into “Eurocommunists.” Peppone had stopped glorifying the Supreme Leader in Moscow. He no longer believed in the religion of Marxism-Leninism. He no longer dreamed of a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Peppone and Don Camillo had entered into a historical compromise. Put in blunt terms, within thirty years Italy’s postwar democracy had managed to democratize—to civilize—the communist enemy.

If you think this story is messy, rest assured that it is even messier than the way I tell it here. The Democrazia Cristiana, the Christian Democrats, entered into many dirty deals—with neofascists, with the mafia. True, their range of choice was limited: The only political power in Italy that was reliably anti-mafia was the Communist Party.

The whole system stank to high heaven of corruption. Although Italy, thanks to the Marshall Plan, experienced its own “economic miracle” in the 1950s and 1960s, the south remained dirt-poor and underdeveloped. But Italy remained a democracy—and a member of NATO. The country suffered during the “years of lead,” from 1960 to 1980, when terrorists on the left and right abducted, maimed, and murdered. But the country was spared the horrors of civil war; and it never descended into military dictatorship, as Greece did in 1967.

What brings all this ancient history to mind? Well, though Donald Trump has lost, Trumpism is alive and kicking. There are signs that a segment of the Republican Party has become an openly anti-democratic force, at least at the national level. For those still in a state of denial, this should have become clear in the days after the election. Faced with Trump’s lie that he won, and his moronic attempts to overturn a democratic election, most Republican senators and congressmen did not dare contradict their Dear Leader because they were afraid of his fans.

So, here we are, faced with a not insignificant minority of Americans who live in a mental universe of their own. This is a universe in which President Biden “stole the election,” the coronavirus is not real, and man-made global warming is a Chinese hoax. None of them is going anywhere. What are we—the rest of us, the silent majority, conservatives and liberals, progressives and Never Trumpers—to do?

First, hope and pray for our own coronavirus-vaccine-aided economic miracle. Second, start the democratic dance. The more extreme elements of the Republican Party must be contained—boxed in, rendered powerless—just as the Communist Party had to be contained in postwar Italy. What might help is the fact that the Democrats, not unlike the Democrazia Cristiana, are not a party but a coalition, one that in Europe would reach from the far left to the moderate right.

This coalition must hold at all costs. Let us remember the most important lesson from the years of shame, aka the Trump Administration: We have our differences, but they shrink to comical near-irrelevance when compared to that.

Perhaps it will not take a whole generation until those Republicans revert to sane conservatives, a right-wing version of the Eurocommunists of yore. Maybe it will only take twenty years.

I’ll be seventy-five then. In the meantime, I won’t spend those years re-reading the adventures of Don Camillo and Peppone.

Hannes Stein, born in Munich, Germany, in 1965, works as a cultural and political correspondent for Die Welt. He has published two novels and his third, Der Weltreporter (The World Reporter), will be published this winter by Galiani Berlin.