There's No Substitute For Public Opinion

What democracy defenders can learn from the presidency of Andrew Jackson.

It was so cold that the president’s second inauguration had to be moved inside. His opponents were depressed and fearful: the president had already seized unprecedented power from Congress, ignored the judiciary, and vetoed federal funding for the home state of his rival. He looked like the politicians in Europe and elsewhere whose personalized control over all the levers of power were destroying liberties in their own countries. The president’s supporters dismissed these worries as contemptible. This was no authoritarian, they argued, but a democratically elected politician of the people who was popular in every part of the country. The powerful were just trying to hold onto the undue privileges of the Washington elite by denigrating an outsider who was the choice of most Americans.

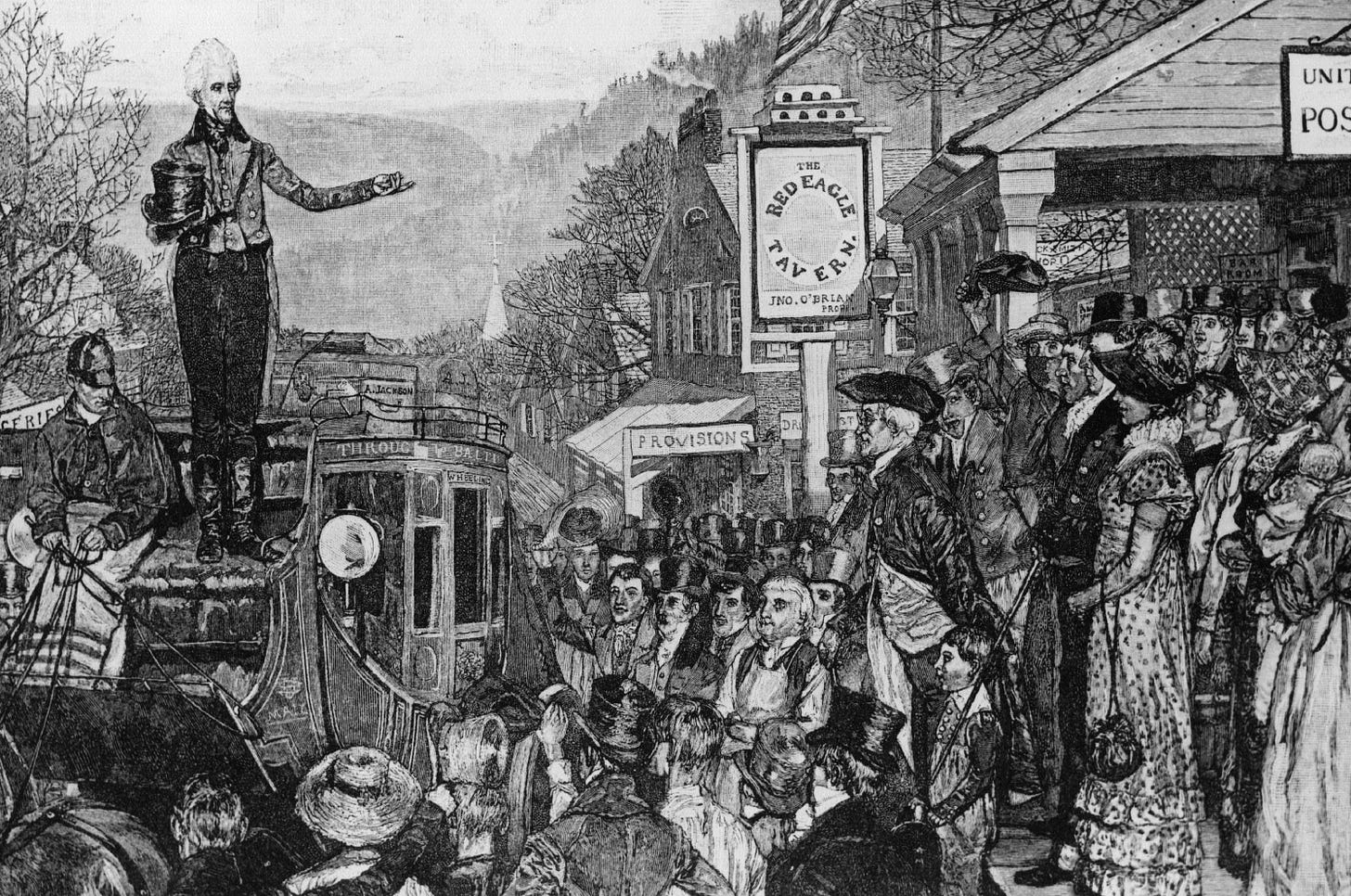

The year was 1833, and the president was Andrew Jackson, whose portrait President Trump hung in the Oval Office during his first term. As is feared today, Jackson used his public support to permanently transform how power was wielded in America. For anyone concerned about democracy in the years ahead, the presidency of the country’s first populist holds crucial lessons.

The most important is the hardest for today’s pro-democracy activists to stomach. Like Trump, Jackson was polarizing, but popular. He won twice, fair and square—and his chosen successor was elected afterward.

Jackson wielded power in ways that went far beyond the guardrails of democracy. His enemies railed against him as a tyrant. But his policies were desired by the majority of voters, and many of his supporters did not care about the means he used to achieve them. Notoriously, Jackson ignored Supreme Court rulings when he forced Native Americans to relocate west of the Mississippi in the Trail of Tears. Many Americans dissented—but like Trump’s campaign against illegal immigrants, there was also a great deal of support for a policy positioned as helping the majority. Feelings among Trump’s base that illegal immigrants use up local services and depress wages are little different than the emotions of Jackson’s supporters. Similarly, Jackson destroyed the independent Bank of the United States—but by painting it, with some legitimacy, as a tool of powerful interests, he ended this independent institution beloved by much of the business community with the support of the population.

These and other policies were popular. Part of that popularity was created by Jackson’s mastering of the communication landscape, which was changing then, as now. National newspapers were new and generally partisan, so Jackson asked his supporter Amos Kendall to create a newspaper from scratch, breathing it into life solely to tell his side of any story and to trumpet his person and his policies. The effect was quite similar to Trump’s use of Twitter and the role now played by X and supportive podcasters in allowing a president and his policies to speak directly to voters without any mediators to ask questions or check facts.

“Old Hickory,” as Jackson was known, also created a new political landscape. He ran the first mass election campaign and created the modern political party, which overtook the former closed-door power politicking of Washington’s elites. His polarizing personality increased voter engagement—in fact, turnout in these years was vastly higher than today, between 70 and 80 percent. Jackson (and his vice president Martin Van Buren, who masterminded the strategy) won these high-turnout contests by doing the hard work of mass organizing. His “Hickory clubs” were precursors to MAGA rallies and allowed people who were often isolated in their daily lives to join with others and proclaim their allegiance as an identity, while enjoying the camaraderie of spectacle-like speeches, parades, and lots of barbecues.

In addition to creating a mass party with genuinely broad support, Jackson and Van Buren figured out deeper, structural ways to cement allegiance. First, they purged the civil service of all those they thought were working against Jackson’s agenda, cutting what is believed to be about a tenth of all civil servants at the time. Then, he claimed that government jobs did not require particular expertise and could therefore be given to any supporter—meaning that those who helped him campaign were potentially eligible for government jobs well beyond the thin layer of political appointees at the top.

He didn’t keep the largesse for himself in Washington D.C.: Members of Congress who voted with him received favorable treatment for their legislation, an important carrot given his unprecedented use of the veto to gain power over the legislative agenda. But they were also given patronage roles they could disburse to ensure their own re-elections. These government jobs were implicitly tied to one’s party allegiance. That system continued long after Jackson—my grandfather, a police detective in the Bronx, understood that he had to take time off to campaign for the ward boss if he wanted to keep his job. This was the “spoils system.” It created a base of party control from the local to the national level. What became the Democratic Party used it for nearly a century after Jackson left office.

It would be easy to say that the country survived the Jacksonian presidency and will surely survive four more years of Trump. It will—and that should reassure us that our situation is not hopeless, nor is it existential to our democracy.

But it is crucial not to be sanguine. The damage Jackson did to U.S. democracy was real and lasting. The Founders wanted Congress to check presidential power. Jackson shifted the balance decisively and forever after towards the presidency by repeatedly vetoing the powers of Congress and ignoring the Supreme Court. The moral blot of Indian removal is a lasting stain. Mob violence grew under a leader who normalized violence in politics and was vehement in quelling the political rights of abolitionists. The spoils system led to decades of corruption in many big cities and in some states, to the extent that corrupt practices continue to be higher in former “machine” cities to this day.

Avoiding a repeat of these long-lasting harms requires pro-democracy activists and organizations to learn how to fight a fairly-elected, genuinely popular president.

For instance, many fear that Trump will engage in undemocratic behavior to place his thumb on the scale of voting. He occasionally speaks about a possible third term, playing with the idea in his own mind and perhaps normalizing it for his supporters and Congress. After all, didn’t FDR serve more than two terms? He wouldn’t be the first. And he clearly is not troubled by laws or traditions. A lot of effort will rightfully go into blocking undemocratic moves. Block-and-tackle efforts within states will be important to ensuring free elections.

But even with that immense work, it is likely that his handpicked successor—perhaps one of his kids—could simply win another term outright because of popular policies, media mastery, and the political realignment Trump is spearheading. That realignment told African Americans they could vote on behalf of their conscience not their color, and treated Hispanics as aspirational small business owners and Christians rather than as a monolith of national origin. The campaign engaged in outreach that was often more classically liberal than the race-and-group based Democratic platform, helping him win more first-time voters, young voters, and fast growing demographics of Hispanics and Asians in 2024 than in 2020. These low-frequency voters might swing back or not vote, but if they turn out in 2026 or 2028 for the Republican Party, their allegiance could become “sticky” and last a lifetime.

Throwing a wrench into this realignment is thus crucial for democracy defenders. To do so, they cannot only play defense. Massive effort and money is going to a coordinated effort of hundreds of impact litigation firms, working together to thwart the most illegal aspects of Trump’s policies. This will be hugely important for preventing actual harm to many real human beings, and reducing the enactment and normalization of illegal policy.

However, lawsuits to stop an agenda are a defensive act. In fact, they can easily be portrayed as lawfare—attempts by liberals to use the courts to pursue their agenda. That spin will undoubtedly allow Trump to engage in quid pro quo lawsuits, claiming that it was done to him first to block a popular agenda desired by voters. While my heart wants to fight every undemocratic move in the courts, my head says that too many lawsuits may further normalize lawfare and delegitimize courts if these moves are not accompanied by a strong communications strategy, which, currently, they are not.

The main arena of the fight for democracy must be the realm of public opinion. Reaching the public requires savvy messaging, improved communications, and smarter organizing.

We will ultimately strengthen our democracy by building an electoral coalition that cares, not by cutting off one or two heads of the hydra in the courts. What will it take to make the public see Trump’s anti-democratic strategies as wrong, distasteful, and not something they want to associate themselves with?

First, pro-democracy activists must stop speaking of Trump as an autocrat or this government as autocratic. Of course, now that they are in office, they are using a playbook of tactics used by leaders in authoritarian countries. Those pesky checks, balances, and laws are what stopped previous American administrations from enacting their agendas (remember Obama’s failed attempt to close the prison on Guantanamo?).

But the way to fight undemocratic methods ultimately rests in changing the minds of those individuals who voted for this government. Calling their elected leader an authoritarian and his government illegitimate in week two is not going to work (though it might in future years).

Many in the pro-democracy community want to deride the president for his ignorance, his lack of respect for institutions like the civil service, and his policy agenda. But those who voted for him are not going to be shocked by Trump’s personality, vindictiveness, or the policies he is pursuing. He has dominated politics in America for nearly a decade. Andrew Jackson’s detractors also saw him as an uncouth despot and continually underestimated him because they could not fathom his popularity. Yet the appeal of personal strength, crushing opponents, delivering on promises, and helping the majority over “special interests” are long-standing political winners. Fighting Trump for what he is is likely to fail.

Moreover, there is majority public support for less government waste, for reducing foreign aid, and for a new immigration regime. For many people frustrated by a government that has long seemed unable to do big things, Trump’s speed and seriousness of purpose is positive: this is what government can do when people at the top mean what they say.

Yet that does not mean that Americans, including Trump supporters, will like all the unintended consequences that emanate from these policies and methods.

Pro-democracy forces should wait for moments of excess that make large groups of Americans, including Trump’s supporters, squeamish, and they should drive these moments home, hard and with repetition over time. The democracy community may well have to move outside of its comfort zone and beyond procedural issues—upset as many of us get at the firing of inspectors general or politicized witch hunts in the civil service, these norms themselves are unlikely to move low-frequency voters.

Instead, a major communications operation should seize on the kinds of issues that have an emotional punch or trigger a strong disgust reaction. The majority of Americans, for instance, do not like the pardons of violent individuals arrested after January 6, 2021. Police unions are particularly upset. Don’t let that story get lost in the general tumult. Each moment of excess should be used to peel off a constituency—law enforcement, military servicemembers, small business owners, the truly religious, those concerned about law and order—and keep it skeptical of Trump over a timespan of years, not a news cycle. More missteps will come: for instance, if National Guard or Army reserve units are used for immigration missions, what will that do to law enforcement or ambulance response times in communities where police and other first responders are also frequently in the Guard or Reserve? First responder response times are not a typical “democracy” theme—but if the time from heart attack to hospital elongates, it will become a kitchen-table issue that connects to an anti-democratic decision. Each crisis must be used to convince Trump supporters that this was not what they voted for. They must be able to embrace democracy while saving face.

The goal is twofold. First, to create a “vibe” in which disagreement and dislike can surface in socially acceptable ways. For example: “I like Trump but I wish he hadn’t done that.” Such vibes allow people to feel they won’t be pariahs for their opinions. The second goal is to impede a realignment if the Republican Party proves willing to enable widespread anti-democratic actions. While a portion of Trump voters are die-hard fans, another segment are Republicans who simply grew tired of the cognitive and emotional effort of voting against their party identity and “came home” in this election. It may be hard to sway either of those—efforts to unstick the voting patterns of identity have proven difficult. But a portion of Trump’s voters in 2024 were low-frequency and swing voters who voted against Democrats. They need a way to claim to themselves and others, “I did not vote for that.”

Communication is key. The mainstream media has shown that it is easy to cow, owing to a highly consolidated ownership structure that often overrides journalistic ethics. Owners refuse to stick with important stories over time. Thus, there is a need for direct communication with voters.

Focusing on political news is unlikely to work at scale—low-information Americans and people gravitating towards new forms of media are tuning out the news much of the time. Instead, the democracy community needs to build authentic relationships with info-tainment influencers, podcasts, and media that already reaches and has trust among smaller sub-cultures: Christians, veterans, truck drivers, and so on. The democracy community will have to learn how to use AI and other new technologies, mixed, of course, with authentic voices and trusted mediums. That will enable them to flood the information landscape when something happens that affects these communities emotionally. Over the next few years, democracy advocates need to help them understand the relationship between issues of outrage and democracy itself.

But pro-democracy efforts will also require that ancient form of information transfer: conversations between people who know each other. This will require local organization, building on existing infrastructure from NextDoor to basketball leagues and book clubs. Americans who are separated are more likely to think the worst of one another, but democracy is built on positive, engaging forms of community at the local level, including friend and family networks that cross partisan boundaries. If those formal and informal relationships are infused with messages that spread hope, joy, and connection, they create a medium through which new messages and “vibes” can pass. Local groups should not start as politically affiliative, or they risk missing the most important targets: those who are less partisan or politically engaged. But eventually, social media and sub-culture outreach will influence these vibes in a more political, pro-democracy manner. Is it amusing that people are starting to enact Nazi salutes in public to reflect their loyalty to MAGA? Or is that something that causes your friend group to shake their heads and move away with embarrassment?

It would also be unwise to ignore the more structural side of Jacksonian politics: the spoils system. Trump’s first two weeks ended remote work for government civil servants. He made tens of thousands of civil service jobs much more precarious. Millions have been offered questionable buyouts to leave their jobs voluntarily. He appears to be creating a list of civil servants he believes are disloyal and firing them without legal process. The general sense is that he is seeking a civil service loyal to him and the MAGA agenda.

A civil service loyal to a party or person, however, could have a major political impact. During the 2024 campaign, Trump promised to move 100,000 government workers out of Washington—a popular idea, and one that he tested on a smaller scale in his first term. Such a move could mean that tens of thousands of government workers who understand that their jobs are incumbent on their loyalty to a party would be added to particular Congressional districts. If this happens, it would have political ramifications reminiscent of Andrew Jackson’s spoils system.

Finally, democratic reformers should be willing to copy the best tactics of their opponents. There is no substitute for a ground game of mass organizing—and MAGA figured out how to do it at scale. One key lesson is building more fun into such work: a little less MSNBC and spinach, a little more YouTube and funnel cakes. Vote buying is illegal, but Elon Musk’s million-dollar giveaways were fun, and reminiscent of the money giveaways of Mr. Beast, the most-watched man on YouTube. If that doesn’t sound like your thing, that’s the point: a democracy movement cannot be built at scale out of upper middle-class professionals who love Bruce Springsteen and take their kids to see Taylor Swift. It must step out of its comfort zone and into the wider popular culture, embracing the celebrities and tropes that resonate with what has become a large counterculture virtually unknown to the professional class.

There also has to be somewhere for disillusioned voters to go. Jackson’s Democratic Party was eventually foiled by the upstart Whig party, which drew support from disaffected Democrats and former members of the other major parties. While they never organized much of a positive agenda, their nomination of a war hero for the presidency, combined with a great depression that could be blamed on Jackson’s destruction of the Second National Bank, led them to victory. They won four presidential contests.

Today, while some low-frequency voters may switch parties, the vast majority of frustrated Republicans are not going to vote for Democrats. It’s simply too hard an identity shift in a country as polarized as the United States. Moreover, the Democratic brand is in free-fall. Like most American voters, moderate-to-conservative Democrats (who compose the majority of the party), think the party’s prime concerns are issues such as abortion and transgender rights, which are not their top priorities. At the same time, the left who compose most of the activist groups claim that voters stayed home because the party was not progressive enough. And no part of the party leadership is willing to confront the fact that misrepresenting the state of Biden’s health in 2024 opened Democrats, just like Trump, to accusations of lying.

This is combined with the fact that third party bids always fail, serving merely as spoilers in the U.S. duopoly, while ranked-choice voting structures that would have let different factions of the same party run against one another failed dismally in the last election.

It is therefore going to be tough, but necessary, to ensure that a realignment does not continue simply for lack of alternatives. If minds are changed, voters need some way to express those feelings where it matters: on the ballot. Perhaps fusion voting—allowing more than one party to nominate the same candidate—could help. A single candidate could garner votes from those who supported a conservative but pro-democratic party, Independents, and frustrated Democrats who want a more moderate alternative.

As Abraham Lincoln said, “public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; against it, nothing can succeed.” If history is any guide, the democracy field needs a vast increase in its communications infrastructure and acumen, from AI and influencers to local connections and camaraderie. And it needs it now.

Dr. Rachel Kleinfeld is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I'd add one tangential but I think important point: in order to persuade you need to have a point of agreement that can be built upon. As the group More In Common continually observes in its reports, Americans do have more in common than we think, and in particular, many disagreements arise from poor understandings of what people in "the other party" believe. sAs a whole, Democrats believe Republicans are worse than they are on issue after issue, and Republicans believe the same about Democrats.

The starting points for these necessary conversations need to start with agreement. Illegal immigration has benefits and it has problems. Can we agree that illegal immigrants who have been convicted of crimes can reasonably be deported, and then discuss whether just crossing the border without going through legal channels is -- maybe -- also a cause for deportation? Or if not that, then maybe more proof for asylum seekers is needed than a statement of some specified fears? These are where conversation can happen, and maybe minds changed -- in either direction, I'd add.

Same with gender and sex. Can we agree that today's understanding of gender is quite divorced from biological sex, and its subjective nature causes problems? And can we also agree that sex is biological. From there, maybe that it is true that some very small number of people really do experience distress because of their sex, and have changed what can be changed so that they can present themselves in accordance with that interior experience. They have not changed those things that biology has bestowed on them (which many transsexuals would not argue with), but that they are living a better life in which they are more comfortable, having given up many important aspects of an ordinary life to do so. And from there, that maybe it is reasonable to acknowledge what puberty does as a boy becomes a man, and place some limits on such things as sports competition or bathroom access if someone has only begun the process of changing their sex, or has little or no intention of doing so, but claims to be the other sex? Or can we come to some agreement that medical interventions for minor children are still scientifically unproven with adequate confidence, and that extreme caution is required to make sure a child's mental health is fully understood by professionals, and parents are well-advised of the gray areas and the risks, as well as the potential benefits?

It's hard to have these conversations if we can't find some common ground first. But in our advocacy-saturated world, we keep giving in to the temptation to assume worse opinions about others than they deserve, and too often neglect interest, first, in what they rationally believe, and trying to find those small points of commonality where a real conversation can begin.

I'd put more credence in a legal strategy, especially when used to counter politically-motivated prosecutions. The standards for evidence in our courtrooms and the power of juries are the best mechanisms to defend and affirm the rule of law. This will take individuals willing to stand their ground, not resign and retreat, and others to engage in civil disobedience, for example by refusing to turn over their workplaces to Musk's lieutenants. It will require the courageous engagement of the civil rights protesters of the 1950s and 1960s. But, when their cases get to the courts, the issues to be resolved will not be abstruse ones of constitutional exegesis, but real world tests of laws that apply equally to both individuals and oligarchs. Juries will be the final arbiters in these cases, and I continue to have confidence in their abilities to see clearly and rebuff the excesses of the moment. More importantly, though, courtroom dramas will help to shape the court of public opinion.