It has now been about 48 hours since Thomas Matthew Crooks, a socially isolated 20-year-old, attempted to assassinate Donald Trump, lightly injuring the former president, and fatally wounding an attendee at his rally.

A lot has already been said: about the danger of an escalatory spiral that will take this country ever closer to the brink, for example, and about the need to abjure all forms of political violence. A lot, for now, remains in the realm of speculation: the effect that this event—and Trump’s defiant reaction to it—may have on the upcoming election and, more pressingly, how someone like Crooks could have come within a literal inch of killing the most famous and controversial man in America. But one important question has, in the avalanche of media commentary about the assassination attempt, so far been mostly ignored.

It is in moments of tragedy or upheaval that the true state of a nation is often revealed. So what does the near-assassination of the most dominant politician in the country reveal about the state of the country, including the strengths on which it can count to get it through the next months, and the weaknesses that make it vulnerable?

Some of the news is good.

Most Americans were saddened or outraged by the attempt on Trump’s life. This included his congressional allies and his millions of supporters, of course. Notably, it also included millions of Americans who deeply disdain him. Both Trump’s predecessor and his successor unequivocally condemned the attempt on his life; so did hundreds of elected officials, progressive organizations, and other political adversaries.

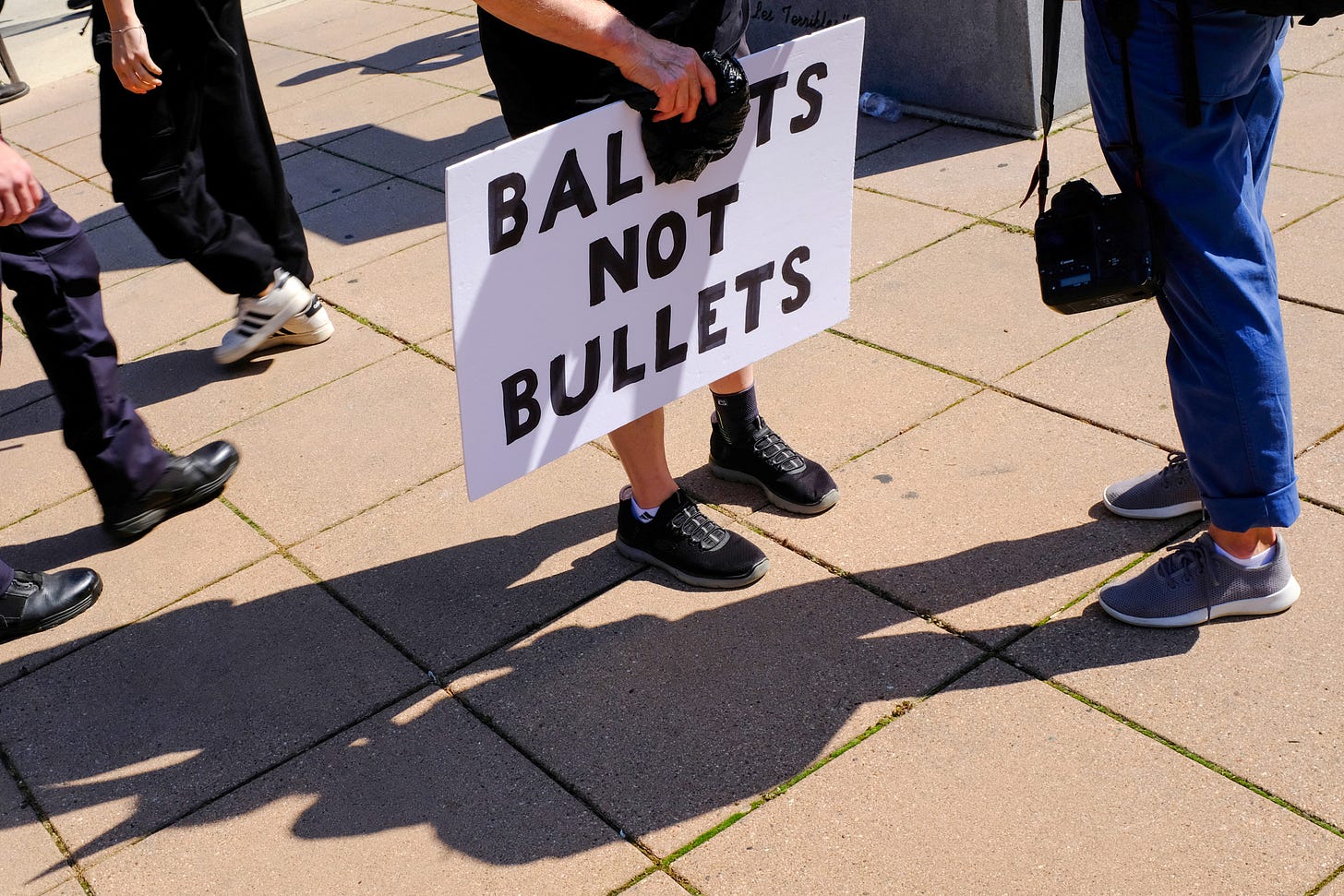

This may not seem like much: the willingness to accept that we mediate political differences at the ballot box rather than in violent clashes on the street is the minimum entrance ticket to a democratic society. But it is a minimum entrance ticket which many societies that, like the United States, are deeply polarized but, unlike the United States, are genuinely on the brink of civil war, refuse to pay.

A lot of the news, however, is bad.

The bad news includes examples of people who reacted to Saturday’s events by glorifying violence, or by mocking its victims. One popular YouTuber with hundreds of thousands of followers, for example, seemed to celebrate the death of Corey Comperatore, an attendee at Trump’s rally who heroically shielded his family with his own body. The people who celebrated violence in this way were a small minority, and they were swiftly “ratioed,” and yet the thousands of likes they attracted demonstrate that a sizable minority of Americans shares their rage.

One of the background conditions that has fueled the rage of the past decade—and has in turn been fueled by it—is a widespread sense that American institutions are failing. Even before we know the outcomes of the multiple investigations into the Secret Service which are now, for very good reasons, underway, it is clear that Saturday constituted an especially worrisome example of that kind of failing.

The Secret Service allowed a gunman to crawl onto a roof that was positioned fewer than 165 yards from the stage and have a clear line of sight to Donald Trump. Spectators spotted the gunman minutes before he was able to take his shot and tried to alert nearby security forces, but these failed to stop Crooks or to lead Trump to safety. A local cop did finally confront the shooter but reportedly retreated when Crooks threatened him with a gun, allowing him to take his shot. Some of the Secret Service agents shielding Trump after the attack appeared panicked and disoriented, with one struggling to put her gun into its holster.

The abject tactical failures of the Secret Service pose structural questions that urgently need to be answered. Why, even in the lead-up to Saturday, has the Service allowed a long series of comparatively minor infractions to accumulate? Did the Secret Service lack the necessary resources to protect Trump? And was the team on the ground sufficiently competent or experienced to handle the incredibly important task to which it was assigned?

As the old saying goes, one should never ascribe to malice what can fully be explained by incompetence. This motto seems especially apt as the dysfunction and incompetence of key American institutions mounts. But it also seems inevitable that, the more aptly this motto describes American society, the more often it will be disregarded. Massive failures of mission like that which occurred on Saturday practically invite wild conspiracism—and, boy, have wild conspiracies had a field day since the assassination attempt.

The first conspiracies came from Trump’s detractors. As soon as the first pictures of his injury emerged, some influential Democratic activists and advisors suggested that this was a false flag operation, designed to strengthen his appeal. Even after that, “Blue MAGA” accounts on X and other social networks suggested that Trump had been hit by shrapnel rather than a bullet, or grasped at straws to deny that the shooter had once made a small donation to a progressive organization.

But the extent of conspiracism was much worse on the right. Elon Musk raised the possibility that the Secret Service’s failure may have been “deliberate” within hours of the attack. Jesse Watters, a prominent Fox News host, admonished his viewers to “be skeptical about what they hear,” preemptively declaring that “we don’t trust the FBI.” Marjorie Taylor-Greene predictably went even further: “this reeks of something a lot more sinister and bitter,” she posted on Sunday. “There are too many things that do not make sense.”

Even the news about violence in the United States is a little less good than it might appear at first sight. It is true, as Rachel Kleinfeld explains in an emergency podcast Persuasion is publishing tomorrow morning, that an overwhelming majority of Americans reject political violence. But it is also true, as she goes on to point out, that most people who engage in violence do so because they claim, whether sincerely or strategically, that they are merely defending themselves against the violent intentions of the other side. And while some extremists on both the left and the right have advocated violence in the last years, and even much more mainstream figures have made mealy-mouthed excuses for such violence in an unforgivable dereliction of civic duty, the extent to which they have done so is now routinely overstated on each side of the political aisle.

Parts of the left have justified some forms of violence in the last years. Movements like Antifa explicitly glorify political violence, reserving for themselves both the right to take action against anyone they consider fascist, and the right to determine who should be included in that category. Even politicians and media outlets that didn’t go so far as to explicitly endorse Antifa made excuses for real forms of political violence in the summer of 2020, when mass protests against racism whose participants really were mostly peaceful persistently devolved into highly destructive orgies of violence fueled by a sizable fringe of activists who really were anything but. Some actively encouraged it, such as when NPR ran an article glorifying looting as a legitimate form of political protest.

All of this is shameful. It must be called out and condemned without hedging or special pleading. But it also shouldn’t be inflated to imply that the Democratic establishment or the mainstream media has in general started to glorify violence. None of it justifies the hyperbole and hysteria to which Taylor Greene succumbs when she tweets that “The Democrats are the party of pedophiles, murdering the innocent unborn, violence, and bloody, meaningless, endless wars. … The Democrat party is flat out evil, and yesterday they tried to murder President Trump.” Nor does it justify the comparatively mild claim by J. D. Vance, whom Trump has today picked as his running mate, that it was Joe Biden’s rhetoric which “led directly to President Trump’s attempted assassination.”

Conversely, there is no doubt that parts of the Republican Party and the conservative movement have glorified political violence in the last years. A succession of campaign ads showed high-profile candidates for office firing heavy-duty machine guns and promising, in the words of one early innovator in the art of gun-toting electioneering, to go “RINO hunting.” And, yes, Trump himself has persistently toyed with endorsements of political violence—whether it be in the form of joking that cops making arrests should not be afraid to bump the head of suspects when throwing them in the back of police cars back in 2017, or more recently by portraying those who took part in the violent assault on Congress on January 6, 2021 as patriots.

All of this is shameful, all the more so for coming from the most senior officials within the Republican Party. All of this must be called out and condemned without hedging or special pleading, something that the conservative media ecosystem have notably failed to do. But here too, a kernel of truth, even one that is worryingly large, is no excuse for overstating the extent to which the other side embraces political violence. And that is something that the most senior Democrats, from Joe Biden on down, have consistently done.

Biden has, for example, repeatedly claimed that he decided to enter the 2020 presidential race after hearing Trump referring to the neo-Nazis and white supremacists who assembled for a deadly rally in Charlottesville in 2017 as “very fine people.” But while Trump was characteristically meandering and irresponsible in his remarks after that rally, he explicitly stated that “I'm not talking about the neo-Nazis and the white nationalists, because they should be condemned totally.”

A charge that senior Democrats have more recently laid at Trump’s feet is even more plainly misleading. Biden has repeatedly claimed that Trump threatened a “bloodbath” if he should not be re-elected. The clear implication is that Trump is threatening that he would incite large-scale political violence if he should lose. But the context of the speech makes it clear that Trump was talking about the economy. He promised to protect American car manufacturing by massive tariffs, and implausibly predicted “a massive bloodbath for the country” if these tariffs were not to be instituted.

The incentives of the mainstream media and the dynamics of social media manage to squeeze any important or nuanced question into a contest between two simplistic sides, a depressing distortion of reality even if one side happens to be much closer to the truth than the other. And so the question of the day has come to be whether it is appropriate to portray Trump as an existential threat to democracy.

Republicans are taking exception to the overheated rhetoric on the left. When The New Republic calls Trump an American fascist, and even puts a visual hybrid of Donald Trump and Adolf Hitler on its cover, they argue, not implausibly, that this runs the danger of inciting violence against him. If it was appropriate to resist Hitler by violent means, and Trump is his modern-day equivalent, then (so goes the tacit implication of the New Republic’s cover), why shouldn’t it be legitimate to resist Trump by violent means?

Democrats are pushing back against this. Trump, they argue, not implausibly, really is a danger to America’s democratic institutions. He really did refuse to accept the outcome of the 2020 elections. He really did incite the mob that ended up storming the Capitol on January 6th. To blame Trump’s critics for inflaming the public mood when they are merely criticizing his inflammatory actions, they charge, is a form of gaslighting.

Depressingly often, in American politics, both sides are badly wrong. In this particular case, it seems to me that both sides are mostly right.

As I have long argued, Trump is a populist who lacks respect for the basic rules of the democratic game. This put America’s democratic institutions under severe strain in his first stint in office, and it is likely to weaken them further if—as seems more likely by the day—he wins re-election in November. Democracy survives on respect for certain rules and institutions, such as the smooth transfer of power and a separation of powers. Trump has been consistently willing to ignore and undermine these fundamental norms when they clashed with his claim to be the sole legitimate representative of the people’s will.

At the same time, it is overly simplifying to insinuate that any politician with authoritarian tendencies is an all-out fascist, or that the process of democratic deconsolidation, which is depressingly common in the world, leads straight to the erection of gas chambers. It is perfectly appropriate—even in the aftermath of Saturday’s unconscionable attack on Trump—to warn about what his presidency may mean for America’s democracy. But there is never an excuse—even and especially when the stakes are truly high—for fear-mongering that distorts the exact nature of that threat.

America is a resilient country. It has many strengths, cultural and institutional, that its own citizens, blind to the even greater extent of dysfunction in many other parts of the world, tend to overlook. It is unlikely that the country will experience a genuine civil war anytime soon, and it has been heartening to see that the attempted assassination of Donald Trump has not, so far, led to any immediate outpouring of retaliatory violence. Some of the most dire predictions made in the last 48 hours have so far failed to come true and may, with the benefit of hindsight, turn out to be overly bleak.

But if moments of tragedy and upheaval reveal the true state of a country, the first draft of America’s report card puts it in danger of failing. Most Americans continue to abhor violence. Our mutual hatred still knows limits. And yet the mix of institutional failure, conspiracist thinking, and partisan fear-mongering is very potent. The risk that it may yet set in motion dynamics which overwhelm the decent instincts of most ordinary Americans remains very real.

Yascha Mounk is the editor-in-chief of Persuasion.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Unsurprisingly, I agree with everything in Mounk’s essay — by 1968, I was a pacifist and conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. That was the most revolutionary year since the Civil War. So, I just want to help people keep things in proportion.

In Feb., the US suffered 2,293 military deaths; about 700 were draftees. This tended to legitimize violence against the government. Also, in Feb., police killed 3 Jackson State student civil rights protesters. In March, the My Lai massacre, which killed about 500 Vietnamese civilians, further delegitimized the federal gov. In April, MLK was assassinated, which led to dozens of urban riots (all political), 43 deaths, 3,000 injuries, and 20,000 arrests. In June, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated.

There were eight more riots in May, June and July.

At the Dem Chicago convention, about 10,000 almost entirely peaceful (though disruptive) demonstrators were confronted, over about 5 days, by 12,000 Chicago police, 6,000 members of the National Guard, and 6,000 US Army troops. A National Commission later described it as a police riot. About 500+ demonstrators were injured. There was also considerable violence against reporters.

So what did our year of revolution lead to? #1 Richard Nixon. But ...

In 1969, the Weather Underground formed and did a lot of bombing, only killing themselves. In 1970, the National Guard shot and killed 4 Kent State students who were dispersing peacefully. Also, the Hard-Hat riot in NY beat up anti-war protesters, and Angela Davis supplied 4 guns used to kidnap a judge, the D.A., and three jurors.

In 1972, the East Coast Panther underground (BLA) started assassinating cops and killed upwards of 10. And the academic left turned very pro-Panther and excused a lot of violence.

And then?

Well, it all began to seem ridiculous, and the women in the movement decided it was too damn macho, and radical feminism took over.

And then?

We got identity politics (1977) and CRT, and the radicals decided it was more effective to claim to be nicey nicey while being sneaky and taking over academia.

And it was much more effective. And it still is.

I find the current far-left politics far scarier than all that political violence, horrible as it was.

Of course, this is a terribly compressed history lesson. But I think it’s a good cautionary tale. Remember the proverb: "Better the devil you know than the devil you don't."