Two Cheers for the French Revolution

Americans misunderstand France’s important—and complicated—place in the history of liberalism.

Persuasion is committed to posting articles that explore the history of liberalism and its competitor ideologies. In that vein, we are delighted to publish this deep dive into the French and American revolutions by The Bulwark’s Cathy Young. In the coming months, we hope to further increase our output of accessible, ideas-driven longform pieces. We hope you enjoy!

— Yascha

Two hundred and thirty years after the start of the “Reign of Terror,” that period indelibly colors the memory of the French Revolution—and is seen as its core essence by its detractors. For American conservatives in particular, it decisively sets the French Revolution apart from the American Revolution, which began two decades earlier: the American Revolution (good) was more conservative than liberal, while the French Revolution (bad) represents liberalism accelerating into radicalism, chaos and murder.

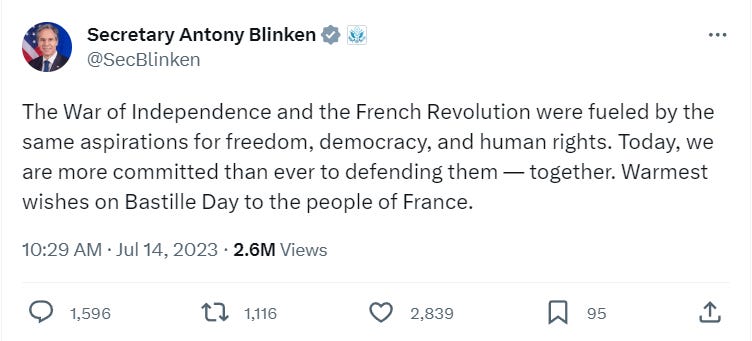

This view was on display last July, when many on the right took issue with Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s innocuous Twitter post with Bastille Day greetings to the French people:

The replies quickly filled up with detractors whose comments ranged from jeers (“This is historically moronic”) to one-line recommendations to read the anti-revolutionary 18th century writer Edmund Burke.

A more analytical piece by Yuval Levin ran in National Review. Levin posits a fundamental difference between the two revolutions, despite some commonalities. The French Revolution was essentially guided by the idea of “a complete restarting of history on novel foundations”—those of Enlightenment rationalism. By contrast, the American Revolution had both conservative and radical elements, but ultimately championed a vision of liberalism grounded in “generations of gradual political and cultural evolution in the West.” In France, the results were ruinous, and the French eventually came to realize that “a more functional free society requires precisely the sort of moderation that their revolution openly rejected.” Levin believes it’s important to understand this truth, elided in Blinken’s July 14 post, in order to avoid the modern temptations of radicalism that seeks to remake the world.

But the French Revolution’s conservative critics are themselves eliding important facts. Its moderate and even conservative side, early on, is rarely remembered because it tends to be overshadowed by later and more dramatic events. Yet it started out as a push for liberal reform. On the opposite side of the coin, the American Revolution, though it was conservative insofar as it aimed to preserve some colonial institutions, was unquestionably radical in asserting America’s right to sever its tie to the British monarchy, in proclaiming that government exists for the benefit and with the consent of the governed, and in abolishing all hereditary distinctions between (male) citizens. We need a more nuanced understanding of the two revolutions from which liberalism was born—one that acknowledges the flawed but radical potential of both.

First, some history. The taking of the Bastille prison by an angry mob on July 14, 1789 is popularly viewed as the start of the French Revolution. But its real beginning was the calling a few months earlier of the “Estates General,” an historical quasi-parliamentary body that had fallen into disuse over nearly two centuries of absolute monarchy, and whose revival was occasioned by France’s fiscal crisis and the need for new taxes. The Estates General opened on May 5, 1789 and soon found itself in conflict with the throne over reforms that King Louis XVI deemed too radical. These conflicts led to the pro-reform majority of the Third Estate (deputies who were not privileged members of the nobility or clergy) proclaiming itself a “National Assembly.”

The people’s victory on July 14 was followed by a formal concord between the Assembly and the new constitutional monarchy that masked an antagonistic push-and-pull. After three years, attempts to save the monarchy finally collapsed and the Assembly voted to proclaim a republic. Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793 by decree of the new representative body, the National Convention. Yet the Revolution continued to radicalize, partly on its own momentum and partly due to external pressures, since the French Republic was now at war with Europe’s leading monarchies. In May, the core of the Convention’s liberal bloc was ousted in a coup which brought to power the radical faction usually known as the Jacobins. In September, “Terror” was made official policy, ostensibly to protect the fragile Republic from domestic enemies. Fourteen months and at least 40,000 dead people later (much more if one counts the suppression of counter-revolutionary rebellions in the Vendée and other parts of the country), the Jacobins themselves were toppled in another coup in 1794, which is generally seen as ending the Revolution’s active phase.

On the surface, this trajectory could not be more different from that of the American Revolution. Yet the denial of commonalities flies in the face of the very real historical links between the two. For one, the Marquis de Lafayette, a key figure in the French Revolution’s early days, was a hero of the American Revolution and a close friend and protégé of George Washington’s. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1789, the foundational document of the new order that sought to replace France’s ancien régime, was drafted by Lafayette in close collaboration with Thomas Jefferson, then still the American ambassador to France.

It’s true that, as Levin points out, the American revolutionaries’ early grievances against the Crown included violations of traditional rights (“taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments”); but accounts of the French Revolution often underestimate the extent to which it, too, began with claims to validate the traditional rights and liberties of the French. That included the revival of the Estates General, which had last met in 1614. In addition, Louis XVI, who initially appeared to accept the Revolution’s demands, was even honored at one point with the title of “Restorer of French Liberty”—and was compared to Henry IV, the 16th century king who promoted religious tolerance, peace and economic development. This is a far cry from, in Levin’s words, “a complete restarting of history on novel foundations.”

Did the French Declaration of the Rights of Man (whose final draft was the work of two moderates, the Marquis de Mirabeau and the Abbé Sieyès) contain a more radical and utopian vision than America’s founding documents? It certainly contained more abstract and philosophical language than the American Bill of Rights, which was written around the same time but is much more specific and pragmatic. The French Declaration featured such vague statements as “The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society” and “The law is the expression of the general will.”

But it also enshrined many of the principles viewed as key to the success of the American experiment: the separation of powers, judicial independence, and the inviolability of individual rights, particularly protections against arbitrary prosecution and punishment. Article VIII states: “No one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.” Article IX elaborates further: “Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable, if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.”

Obviously, in a few years, these principles were less than a fiction. The separation of powers fell by the wayside when the executive—i.e. the monarchy—was literally decapitated, and an independent judiciary never developed. The Terror killed at least 40,000 people, probably many more. The authors of the Declaration of the Rights of Man themselves escaped the guillotine by fortuitously dying (Mirabeau), fleeing France (Lafayette), or lying very low (Sieyès).

Why, then, did the French Revolution, unlike its American counterpart, go so wrong?

The French Revolution began as a domestic battle against the reactionary aristocracy and the proponents of absolute monarchy; it was won with the violence of crowds, which always posed the threat of what the American Founders called “mobocracy.” Popular unrest was fueled and intensified by desperate economic conditions often bordering on famine. Eventually, revolutionary France found itself embroiled in foreign wars as well, with a very real threat of foreign invasion. To some extent, the Terror was unquestionably a response to this clear and present danger, though of course it’s neither a sufficient explanation nor a justification for the violence of that period.

By contrast, the American Revolution was essentially about independence from the British Crown; King George and his government were thousands of miles away, and the use of force to settle the conflict came primarily in the form of a war in which violence was regulated and contained by rules and discipline. By the time the United States came into existence as a nation, the war was over, and the newly formed republic faced no external threats.

French liberalism also faced the gargantuan task of dismantling a vast and elaborate system of feudal and aristocratic privileges; colonial America had nothing remotely similar, despite the existence of a local aristocracy. The early French revolutionaries’ attempts to build on existing traditions of liberty failed not because they were universalist utopians, but because France, unlike America, had no functional institutions suited to liberal governance.

Religion was another factor. Colonial America was a society based on pluralism that could accommodate the religious liberty protected by the First Amendment without much turmoil. In ancien régime France, the Catholic Church was a vastly powerful and wealthy institution, oppressive, riddled with corruption, and (despite the existence of a stratum of liberal clerics) entrenched in its opposition to intellectual freedom and religious tolerance. Much of the political conflict after 1789 had to do with the Assembly’s efforts to break or curb the power of the Church and the King’s resistance to these reforms, based on his own Catholic faith. As the war between the Church and the Revolution escalated, priests, monks and nuns were singled out for particularly savage repression, even before the “formal” start of the Terror in September 1793. It hardly needs to be said that the pre-revolutionary power and reactionary politics of the Church do not excuse any of those atrocities. However, it’s a fact that the role of the Church in France created a hotbed of intense conflict that was not present in post-independence America.

In addition, while the first cohort of French revolutionaries was no more utopian than America’s Founders, there was one way in which the American revolutionaries were much wiser: they were, from the beginning, far more concerned about “mobocracy.” The American Revolution did feature far more political violence than is often recognized, with plenty of vicious attacks and intimidation toward Crown officials and ordinary Loyalists. Yet partly because leading Patriots were fairly unambiguous in their disapproval of such tactics, they remained limited and seldom fatal.

By contrast, in France, the euphoria of the Revolution’s early days caused even moderates to look the other way when the crowds at the Bastille lynched its governor and killed several other people, then paraded with severed heads on pikes. A few months later, in October 1789, a women’s march to Versailles that turned from a boisterous protest to a murderous assault became another revolutionary victory, forcing the King to sign the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The Assembly’s subsequent attempts to rein in the mob inevitably collided with the celebration of such events, found in popular pamphlets such as the journalist Camille Desmoulins’s Lamp-Post’s Speech to Parisians, and prints with satirical depictions of the victims carrying their heads. It’s indisputable that this early violence, and the willingness to condone it, paved the road to hell.

There was also, no less important, the human factor. The American Revolution was blessed with some genuinely outstanding leadership. In the French Revolution, the constitutional monarchy foundered on the weak character of Louis XVI (a half-hearted reformist whose typical modus operandi was to try to assert his authority and then cave under pressure) and was finally doomed by the royal family’s disastrous attempt to flee the country in June 1791. The moderate revolutionaries were well-intentioned but ineffective (and sometimes corrupt), and often seemed to have an unerring instinct for making the worst possible decision in a given situation. The Jacobin faction was dominated by proto-totalitarian fanatics: people like Maximilien Robespierre, who spoke of enforcing virtue through terror, and Louis-Antoine Saint-Just, who wrote that “what constitutes a republic is the total destruction of everything that stands opposed to it.”

Finally, in comparing the French Revolution and the American Revolution, one cannot forget that the American republic had its own grave flaws. If the French Revolution’s progressivism ultimately spun out of control into murderous radicalism, the American republic’s conservative tendencies manifested themselves in an ultimately untenable constitutional compromise on slavery; the result was still a national carnage, only delayed by 80 years. That’s not to mention the rise of violent “mobocracy” in American politics in the decades before the Civil War—or, of course, the violence of slavery itself.

In a sense, then, both revolutions were flawed and stumbling steps toward liberal democracy. The French Revolution stumbled far more egregiously, as its devolution into the Reign of Terror shows; but it also started out with far more insurmountable challenges. The underlying aspirations rooted in Enlightenment principles were the same—an important point to remember at a time when some conservative ideologues try to detach the American Revolution from the Enlightenment altogether.

The Reign of Terror also demonstrated that ostensible commitment to principles such as liberty, reason and universal human rights is not a sufficient safeguard against descent into barbarism or fanaticism. It stands as a crucial reminder of the dangers of utopianism and of zealotry in progressive garb. Still, the Enlightenment-based vision, tempered with humility and a realistic understanding of human possibilities remains, even today, the best foundation for a free and peaceful society.

Cathy Young is a writer at The Bulwark, a columnist for Newsday, and a contributing editor to Reason.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Well said. I find Blinken's Tweet innocuous to the point of banal. The American and French Revolutions were both manifestations of the spirit of the age, which saw political revolution not only in those two places, but in Latin America and Haiti as well, all of which were self-consciously guided by groundbreaking declarations of human rights, the great expressions of the Enlightenment era political awakening that continue to inspire, or ought to.

That age of revolution constitutes the modern invention of human rights, and that's its enduring legacy, despite the various ways revolutions of the time turned sour or failed to live up to their liberal promise. They struck a decisive blow against absolute monarchy and caste privilege, establishing liberal principles as a new normal over the long term. When Napoleon said that he was the Revolution, it was not mere self-serving grandiosity. Even as he shred democracy, he did accept the revolutionary ideals of civil equality, fair opportunity, and meritocracy.

There's a reason French patriotism to this day harkens back to the Revolution, despite the dizzying intervening regime changes. Neither France, nor Europe, nor the world was the same after the French Revolution, and France would never go all the way back. Like the American Revolution, it represented a durable assertion of (1) a national identity and character (2) grounded in universal principles of liberty and equality.

The author's point about slavery is instructive. She might have also noted that France abolished slavery in its colonies at the height of the terror (only for it to be reinstated under Napoleon). My point isn't to excuse the terror because the terrorists -- Robespierre himself -- did the right thing on slavery, any more than it is to excuse American slavery because America avoided a French-style terror, but merely to suggest that those who would condemn the French Revolution on its not insignificant specific failings sound a bit like those who argue, 1619-ishly, that America's founding is likewise little more than a massive crime scene. Both sorts of critics, I suggest, miss the forest for the trees.

I'm not sure if the writers write the headline in Persuasion, but I really hope Young is not offering two cheers for the horror show that was the French Revolution.

The fact that the preliminary stages were more moderate, or that their task was more difficult than that of their American counterparts, hardly excuses the bloodbath that followed.