What's Really Wrong with the "Deep State"

Purging career civil servants will not make government more democratic.

This article is part of an ongoing project by American Purpose on “The ‘Deep State’ and Its Discontents.” The series aims to analyze the modern administrative state and critique the political right’s radical attempts to dismantle it. Click here to subscribe to Francis Fukuyama’s blog and American Purpose at Persuasion to receive future installments into your inbox!

One of the oldest and loudest conservative complaints about the way America is governed concerns the “administrative state,” or what in the Trump era came to be called the “deep state.” The term “deep state” comes from countries like Egypt and Turkey where the security services acted for many years as a shadow government. The United States has never had a deep state in this sense, except in the fevered imaginations of the MAGA right. It does have a permanent civil service that operates at federal, state, and local levels, and it is these that have become a regular conservative punching bag.

The last few months have seen the emergence of two separate salvos against the administrative state. The first was the publication of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, whose authors outlined a plan to revive Executive Order 13957 issued at the conclusion of the first Trump administration creating a new “Schedule F.” This order, which was immediately repealed by Joe Biden, would have given the president the authority to fire any federal servant at will, and replace him or her with a political loyalist. I discussed the dangers of a revival of Schedule F in a previous post originally published in American Purpose and now reprinted for Persuasion here. Many conservatives believed that Trump’s policies had been stymied by a permanent federal bureaucracy staffed by hostile liberals; Schedule F would have removed this check on executive power and threatened the jobs of tens of thousands of civil servants.

The second initiative was the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright v. Raimondo decision issued in late June that abolished the 1984 Chevron Deference precedent. Chevron Deference provided a rule under which the courts would defer to the expert opinions of executive branch agencies in situations where a Congressional mandate was ambiguous or unclear, and the agency position seemed reasonable. Chevron deference had been in the crosshairs of conservatives for decades, on the grounds that it delegated way too much discretion to federal agencies in disregard of Congress and popular will. The Loper Bright decision invalidated a rule issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service requiring Atlantic fishing boats to carry, at their own expense, inspectors judging compliance with rules against overfishing. In ruling in favor of the fishing companies, SCOTUS invalidated the Chevron precedent entirely. This decision built on the same narrative feeding the Project 2025 plan: the administrative state had grown into a monster that made decisions harming the well-being of citizens without any fundamental democratic accountability. There have been dozens of judicial decisions made over the past 40 years based on Chevron, and its overturning may open a wave of litigation seeking to reverse long-standing regulations.

Before accepting this critique, it is useful to step back and think about the nature of modern government. At the heart of the conservative critique of the administrative state lies a vision of democratic government “of the people, by the people, and for the people,” in which citizens would deliberate together on policies, and would themselves be responsible for carrying them out much as one imagines occurred in the proverbial New England town hall. The problem, however, is the extreme complexity of the tasks that modern government is expected to accomplish. While some local issues could be settled on a local level, modern government does things like manage the money supply, regulate giant international banks, certify the safety and efficacy of drugs, forecast weather, control air traffic, intercept and decrypt the communications of adversaries, perform employment surveys, and monitor fraud in the payment of hundreds of billions of dollars in the Social Security and Medicare programs. None of these functions can be performed by ordinary citizens; they must be delegated to experts whose life work centers around the complex tasks they perform.

Substantial delegation is therefore necessary. Some conservatives believe in a Constitutional “non-delegation doctrine,” but Congress has been delegating responsibility for complex tasks ever since Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton was given the job of cleaning up Revolutionary War debt by the first Congress of the United States.

Nor is it the case that the people’s elected representatives have no means of monitoring and holding accountable the bureaucracy they have created. There are both ex ante and ex post methods for doing this. Ex ante, Congress can and has established detailed rules for how the government procures goods and services, hires new employees, and regulates commercial entities. In 1946 it passed the Administrative Procedure Act, which requires rule changes by the federal bureaucracy to be publicly posted in the Federal Register, where they could be read and criticized by ordinary citizens. Political principals in any administration exert substantial control through their ability to appoint and remove subordinates. Ex post, Congress can hold hearings and inquiries into the decision-making by federal agencies. Most senior cabinet officials can expect to spend a huge amount of their time testifying before the myriad Congressional committees that oversee their work.

There are, in other words, a huge number of mechanisms by which the political layer can control the administrative layer. There are of course specific cases of bureaucratic overreach that have become legendary, like Sackett v. EPA, where the Environmental Protection Agency declared a landlocked house to include “waters of the United States” because seabirds may choose to nest there, or the vast expansion of Title IX authority by the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights under the Obama administration.

The problem in these cases was not, however, an out-of-control bureaucracy exerting unaccountable power over citizens. The problem was a failure by plaintiffs to make use of the specific powers—the checks and balances—that the system made available to them. The failures of the early Trump administration to get its way cited in Project 2025 were largely due to the inexperience of that administration’s political appointees. Anyone who has worked in the federal government knows that a knowledgeable and experienced administrator can bend the bureaucracy to his or her will over time. If they are unable to accomplish this, they can call on Congress to provide them with adequate powers. But our currently polarized and dysfunctional Congress has been missing in action over several administrations, failing to provide clear guidance to bureaucrats. Oftentimes, passing a statute requires being deliberately vague on exactly what powers are delegated to the bureaucracy, in hopes that the agencies and the courts will clean up the mess later.

Schedule F will not fix this problem, but it will make the government less competent and vastly more politicized. To see why, we need to step back and look at the history of the American civil service.

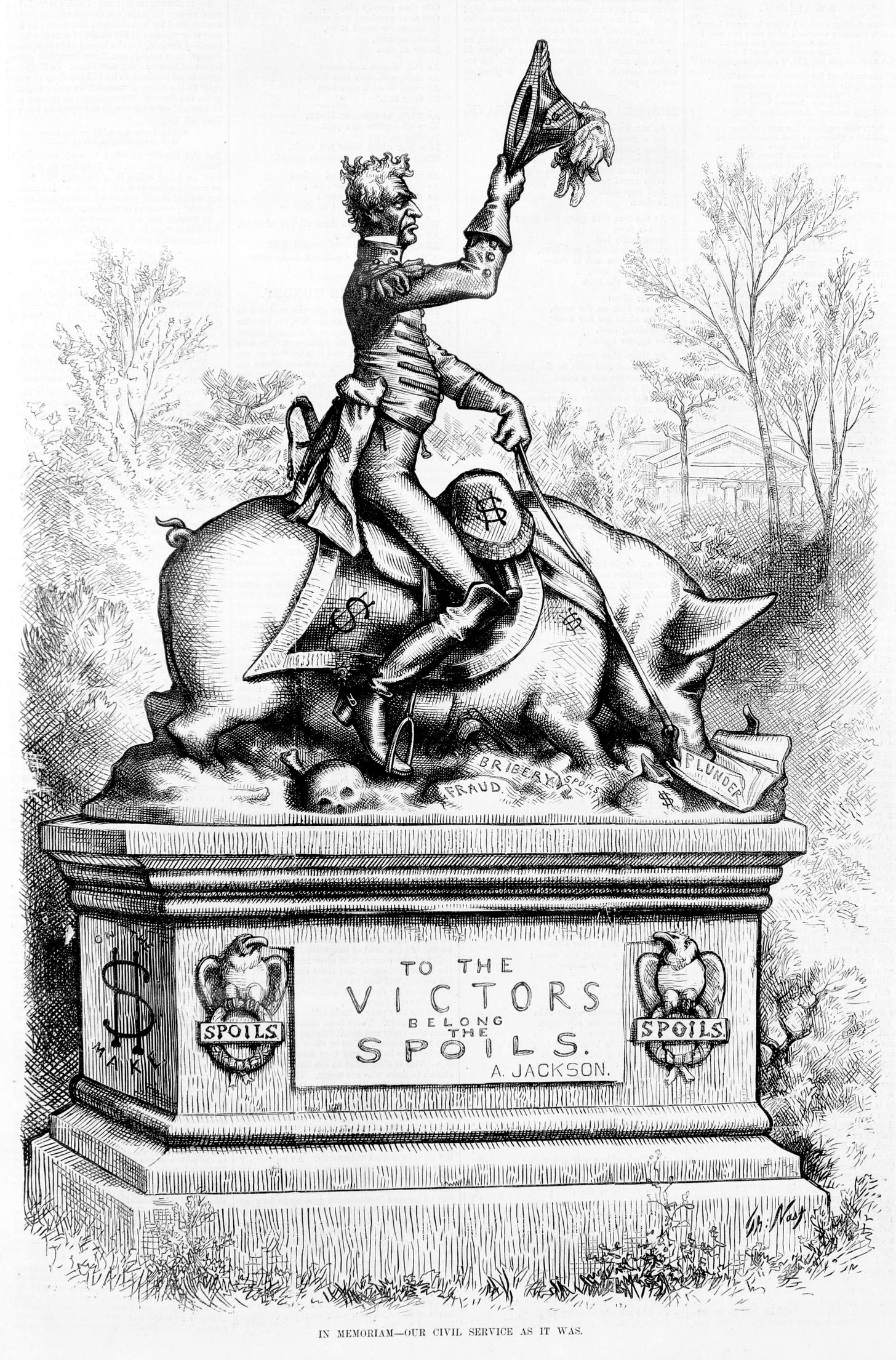

Removal of the property qualification for voting by most U.S. states in the 1820s vastly expanded the franchise to all white men. Politicians soon discovered, as they subsequently did in other new democracies, that the easiest way to get people to the polls was to bribe them—perhaps with a bottle of bourbon, a Christmas turkey, or a job in the post office. Thus began what was known as the patronage or spoils system, under which virtually every job in the civil service was given out by a politician in return for political support. The father of this system was our first populist president, Andrew Jackson, elected in 1828. Jackson declared that he won the election and should be able to appoint the people who would run the government, and also that any ordinary American was capable of doing the job.

This system characterized the federal bureaucracy up through the 1880s, when a coalition of business and civil society groups began agitating for a more professional civil service. Most European countries had already modernized their bureaucracies by this point: the French after the Revolution with the establishment of the Grandes Écoles, the Prussians with the Stein-Hardenberg reforms of the 1820s, and Britain in mid-century with the Northcote-Trevelyan reforms.

The American patronage system was hugely corrupt, and provided opportunities for state capture by big business interests like the railroads that were spreading across the country. Congress did not want to give up its patronage powers, but eventually passed the Pendleton Act in 1883 that created a U.S. Civil Service Commission and established the principle of merit as a condition for hiring and promoting bureaucrats. This occurred only after the assassination of President James A. Garfield by a disappointed office seeker, an act that shamed Congress into acting. Even so, Congress was slow to give up its patronage powers; it was not until the time of the First World War that a majority of federal bureaucrats were appointed under the merit system.

The fundamental problem with a new Schedule F, as noted in my previous post, is that it will return the country to the period before the Pendleton Act, when political loyalty rather than merit, skill, or knowledge will be the primary criterion for government service. Indeed, some conservatives espousing theories of the “unitary executive” believe that the Pendleton Act itself was an unconstitutional intrusion by Congress on the president’s authority. It took President Trump nearly four years (and 44 cabinet secretaries) to rid his administration of seasoned professionals and replace them with loyalists like Kash Patel at Defense or Jeffrey Clark at the Justice Department. This gives us a taste for the quality of officials who are likely to come in under a revived Schedule F. The doors to patronage, incompetence, and corruption will be thrown wide open.

The Supreme Court’s invalidation of the Chevron Deference stems from the same belief that the federal bureaucracy is staffed by liberals who have been substituting their policy preferences for those of elected officials. While it is harder to predict the consequences of this decision than in the case of a revival of Schedule F, it nonetheless is fundamentally wrongheaded for reasons that I will discuss in a future Frankly Fukuyama post.

Francis Fukuyama is Senior Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. He writes the “Frankly Fukuyama” column, carried forward from American Purpose, at Persuasion.

Do you know anyone else who would like to receive Francis Fukuyama’s regular writing straight into their inbox? Please spread the word by sharing this post.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I agree with you on Trump's Schedule F proposal, and its necessarily erosive effect on the civil service. But I think you're reading more into the Supreme Court's Loper Bright decision than is there.

The majority made clear that the proper expertise of the administrative state was not at issue in the case. Experts in the innumerable fields covered by our enormous regulatory bureaucracy are needed and relied on every day. But what they are not expert in is interpreting the law. That is what courts do under the Constitution, and that is what the Supreme Court said.

Deference under Chevron was to agency interpretations of the statutes that govern them, not to their expert opinions about the subject matter they have demonstrated in order to be hired into their positions. Scientists, oceanographers, nuclear physicists, epidemiologists and so many more valuable government employees are not well qualified to do what judges do -- especially appellate court and Supreme Court judges) every day in interpreting complex or ambiguous or poorly drafted laws.

Nevertheless, even under Loper Bright, and agency's considered thoughts about the scope of the law will still be considered -- as they have always been -- as part of the record judges will rely on in interpreting the scope of the law governing the agency. Courts may in fact agree with the agency interpretation if it seems to accord with principles of legal interpretation, something that does tend to get left out of criticisms of Loper Bright.

Chevron deference was both unusual and discordant with the ordinary way courts act in legal interpretation, which is why it has been so roundly ignored in recent years. There are serious doubts about whether Loper Bright will change much of anything in the end. I am a natural born skeptic and doubt all predictions and speculation, which seems to be 80 percent of all public opinion these days. Maybe the doomsayers are right, but time and experience suggest to me that the saying of doom is seldom doom's precursor.

One of the concerns of the Founders was that a republic would only work in a relatively small state. And they were dealing with one in which the voting population was far more selective and homogeneous than it is today. There is an argument to be made that we’ve become simply too large and diverse for our blueprint (The Constitution) to function effectively. I would not like to try to make that argument, but the gradual but increasing level of polarization we’ve been experiencing since the fifties, particularly because of the repeated shocks to large segments of the conservative Christian right of the Supreme Court’s decisions in Brown v Board (repealing the obscenity of Plessy v Ferguson), Engel v Vitale (school prayer), Roe v Wade (abortion rights) , Virginia v Loving (interracial marriage), and Obergefell v Hodges (same sex marriage), much of which today’s court seems intent on rolling back really is resulting in at least two very distinct national visions.

To me, an old white guy of 79, a veteran, and one who taught elementary school American history for over 40 years, the major difference emerging in all this is pretty straight forward. One vision seeks to increase human rights and the other seeks to restrict those rights. One vision seeks to enlarge the definition of what it means to be an American and the other seeks to narrow that definition.

I know I seem to have wandered a bit far from the topic of Dr. Fukuyama’s piece, yet I can’t help thinking that the larger question is one of an increasing sense of loss of control on the right. The concept of a bunch of liberals (read socialists, communists, Marxists, etc) taking control of the nation from the hands of those who seek that restriction and that narrowing is not far from a feeling of loss of control over the ‘administrative state'. That is certainly clear in the right’s attempts to trash 'the experts’. One can almost imagine a bunch of Jefferson’s yeoman farmers (one of which he certainly was not!) refusing to take suggestions, advice, or worse yet regulation from some agricultural ‘expert’ come from that den of elitism in the ‘big ciies’ or worse yet, the central government in Washington DC. I mean what the hell do they know?!

But of course, as Dr Fukuyama points out, we are no longer Jefferson’s nation of yeoman farmers, and we haven’t been at least since the latter part of the nineteenth century. I am reminded of Socrates who, perhaps with a bit of disingenuousness remarked in effect, “The wisest among us is the man who knows that he may indeed NOT know everything”. It is a lesson the current right wing expert trashes might remember, but likely will not.