Why America Became the Great Satan

Anti-Americanism is a product of the mullahs' own ideological and strategic calculus.

This article is brought to you by American Purpose, the magazine and community founded by Francis Fukuyama in 2020, which is now proudly part of the Persuasion family.

by Ladan Boroumand

Why do Iran’s rulers call America the Great Satan and the leader of world arrogance? Why have the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran and his successors always seen America as the enemy of their regime? What has the United States done to the Islamic regime of Iran to deserve repeated unconventional attacks—at the cost of many American lives—whether direct or committed through proxies?

To ask another set of questions: Why have all the diplomatic efforts of U.S. presidents, including Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden, been unsuccessful? Why have Iranian authorities never accepted a modus vivendi with the United States, even as they have readily made alliances with Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, who consider Shi’a Muslims to be heretics, or with the atheist and communist regimes of North Korea, the old USSR, and even China (which actively persecutes its Muslim population)?

Ayatollah Khomeini openly declared the Islamic Republic’s hostility to America when he condoned the storming of the U.S. embassy on November 4, 1979. He justified this action with a litany of grievances against Iran’s former ally, branding it as the Great Satan. Among these grievances, two have been and are still persistently highlighted: the American-sponsored 1953 coup against liberal nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, who had nationalized Iran’s oil industry; and America’s hostility against the Islamic revolution in 1978-79.

The recurrent reference to the 1953 coup by Iranian diplomats serves their anti-American rhetoric, allowing them to portray their military and political intrusions in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen as part of a legitimate “axis of resistance” against American imperialism. The hostage takers believed, or so we are told, that the Shah’s arrival in New York for medical treatment on October 22, 1979 was proof of the U.S. government’s conspiracy against their revolution.

More surprising however is how large the coup looms over and shapes the American debate on the Iranian question. When Americans wonder “Why Iran Hates America” (in fact most Iranians don’t), the 1953 coup is always cited as America’s original sin. The storming of the U.S. embassy in 1979 is similarly explained as being part of the students’ and the mullahs’ desire to avert a new American-sponsored coup against the Islamic Republic.

There is a long list of the Islamic regime’s bloody attacks against the United States in the past 45 years. They are often depicted as the Islamic regime’s response to real or perceived U.S. hostilities. Rarely are they presented as the outcome of the Iranian leaders’ independent and proactive agency, driven by their own ideological and strategic calculus. Hence, past U.S. actions, especially its support for the 1953 coup and its perceived hostility toward the emerging Islamic Revolution in 1977-79, have profoundly influenced the perceptions of U.S. decision-makers and the American public regarding relations with Iran.

But what if we discover that the 1953 coup was welcomed by Ayatollah Khomeini and would not have succeeded without the active complicity of proponents of political Islam? And if we also discover that the United States not only refrained from opposing the Islamic Revolution but inadvertently supported its emergence and empowered its agents? How then could the storming of the U.S. Embassy and Ayatollah Khomeini’s virulent enmity against the United States be explained or excused? If the alleged reasons for Iran’s enmity against the Great Satan are shown to be untrue, then their presumed effects must be attributed to different causes. Before looking for these causes, we need to set the historical record straight.

The 1953 Coup

August 19, 1953, was the day Prime Minister Mosaddeq’s house was stormed by a mob and the Shah’s military forces, leading to his overthrow.

The American semi-official version of the events, leaked in a newspaper article by the CIA in 1954, revealed the CIA’s pivotal role in the coup’s success. “Another CIA-influenced triumph,” the article claimed, “was the successful overthrow, in Iran in the summer of 1953, of old, dictatorial Premier Mohammad Mossadegh and the return to power of this country’s friend, Shah Mohammed Riza Pahlevi.”

The U.S. official narrative on the 1953 coup has radically changed since the publication of the 1954 article. American officials have publicly and critically reassessed this chapter of Iranian-American relations. Their statements about the Mosaddeq era had been prompted by a desire to please the Islamist revolutionary regime of Iran and to mend relations with the country. In 2000, as a token of America’s good faith toward the Islamic Republic, U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright apologized for the 1953 coup. For the same reason, in 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama publicly acknowledged his country’s “role in the overthrow of a democratically elected Iranian government.”

These official and public mea culpas were both ineffective and ironic. They were ineffective in that they did not mitigate the Islamic Republic’s hostility toward the U.S.; they were ironic in that they were directed at the wrong addressee. American officials were expressing their regrets to a political faction (i.e., proponents of political Islam) whose support and active role had been instrumental in the overthrow of the Mosaddeq government. For in fact, the “popular insurrection” against Mosaddeq that the CIA was so proud of was the outcome of a collaboration among some Shi’a religious dignitaries, the British and American intelligence services, and pro-Shah military officers. Without the active participation of anti-Mosaddeq clerics and their ability to mobilize the mob, the operation would not have succeeded, as was noted in a top-secret British memorandum dated September 2, 1953.

CIA historian Scott Koch confirms the crucial role of these CIA-funded demonstrations, writing, “The size and fervor of the demonstrations were critical in encouraging the military to come down on the side of the Shah and [his appointed] Prime Minister Zahedi.”

Not yet an Ayatollah, the 51-year-old Khomeini favored an active role for the Shi’a clergy in politics, but he did not have the necessary prestige and religious credentials to successfully advocate for this view. He did, however, approve of the pro-coup activism of Ayatollah Behbahani, the recipient of the CIA funds, and he favored Mosaddeq’s overthrow. Back then, Khomeini was a member of the entourage of the highest-ranking spiritual leader of the Shi’a community, Ayatollah Borujerdi. Like the majority of the traditional clergy, and much to Khomeini’s chagrin, Borujerdi was a quietist, opposing the clerics’ direct involvement in politics. Borujerdi refrained from making any public statement, whether against or in favor of the coup. But his 45-minute-long meeting with the Shah on March 15, 1954, sheds retrospective light on the silent acquiescence of the uncontested spiritual leader of the Shi’a community.

When American foreign policy and intelligence decision-makers were contemplating the overthrow of the Mosaddeq government, they were thinking in terms of the control and stability of the oil market, the containment of the Soviet Union, and keeping Iran within the Western alliance. These factors were constants in their minds, whereas the Iranian social forces they either suppressed or reinforced in pursuit of their goals were the variables in the equation.

From an Iranian perspective, however, foreign meddling acted as a variable within a century-long socio-political dynamic that produced the constants of Iran’s political equation. Shi’a clergy’s hostility toward Mosaddeq is not rooted in international relations but in Iran’s long-term internal social dynamics, which traces back to the mid-nineteenth century. During this period chronic financial, commercial, religious, administrative, political, and military crises, aggravated by the fierce Anglo-Russian rivalry for control of the country, had led to a constitutional revolution (1906-11). Iran’s first written constitution transformed its tribal monarchy into a constitutional monarchy endowed with a representative government based on the sovereignty of the people, freedom of the press, and the reinvention and separation of the legislative, executive, and judicial powers. The term “people” was not entirely inclusive, as it excluded women and paupers, but the underlying shift from a traditional tribal worldview to a modern, proto-liberal, almost democratic one was truly remarkable.

During the following years, traditional and emerging social forces clashed and interacted in a chaotic nation-building process. Overall, modernizing social forces prevailed over traditional despotism and the clerical worldview. Reza Shah Pahlavi, a strong-willed, self-made colonel of the Persian Cossack Brigade, rose to power with encouragement from the British government and in 1925 founded a new dynasty, which pursued an authoritarian modernizing agenda. In the following decades, a confused clerical establishment, having lost its cultural and judicial preeminence, tried to redefine itself and its role within the new secularizing nation-state. Meanwhile, the liberal-leaning founding forces of the constitutional revolution had been sidelined, but they were waiting for a historic opportunity to revive the revolution’s liberal-nationalist agenda.

This historic opportunity arose with the occupation of Iran by the Allied forces in August 1941. Their subsequent dethroning of Reza Shah—who had declared Iran neutral in the conflict and maintained amicable relations with Germany—revived the parliament and partially restored the constitution’s authority over the country’s political life.

The new political freedom brought by the Allies revitalized political rivalries and competition among social and economic forces. Political parties burgeoned and competed. Notwithstanding their divergent agendas, they all seemed united against the abusive rule of Great Britain. The new Shah, however, was not content with his limited constitutional power. Striving for more influence over the parliament and the government, he saw Prime Minister Mosaddeq as an obstacle. As for the clerics, while most of them stayed aloof from direct involvement in politics, many did not shy away from influence peddling. The liberal-leaning Mosaddeq had benefited from the backing of the main social forces for the nationalization of the oil industry, but he lost the support of Islamists when he refused their demands that he impose the veil on female state functionaries, ban the sale of alcoholic beverages, introduce Shari’a law into Iran’s modernized penal code, tamper with elections in favor of their chosen candidates, and (most crucially) persecute the Baha’i religious minority.

From the Iranian perspective, then, the constants in 1953 included the presence of illiberal nationalists, liberal nationalists, and religious reactionaries, while the variables were British, American, and Soviet policies. (Soviet influence was predominantly exerted through local communist proxies.)

In 1953, Khomeini favored the ephemeral alliance between the Shah and religious reactionaries. He viewed the coup as a providential “chastisement” well deserved by an enemy of Islam. For “had he [Mosaddeq] stayed on, Khomeini claimed, he would have harmed Islam.” Fifteen years later, he still viewed the newly revived pro-Mosaddeq National Front (NF) with suspicion:

I know their roots. This [NF] is a group that has always been staunchly against Islam and the clergy, right from the beginning of its formation. … [In] those days, he [Mosaddeq] was their leader, in whom they take pride today. He, too was not a Muslim...

Khomeini’s diatribe was incited by the National Front’s entry into dissidence in mid-1981. NF had publicly opposed the violations of civil and political liberties, the suspension of the freedom of political parties, the ongoing political assassinations, and the introduction of Shari’a law into Iran’s modern penal code. The ayatollah’s tirade concluded with an anathema: the NF was “Kafir” (infidel).

Thus, Khomeini banned the pro-Mosaddeq organization on charges of apostasy, despite many of its members being pious Muslims. Ironically, during the same period, Iran’s atheist, pro-Soviet Tudeh party faced no charges of apostasy nor was it banned. Predictably, the Islamic regime has glorified the coup’s clerical protagonists by issuing commemorative stamps bearing their effigies.

On August 19, 2019, Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif cynically tweeted, “Sixty-six years ago today, a coup instigated by the US and the UK overthrew the democratically-elected Government of Iran.” Zarif conveniently failed to inform his international audience that his government had banned any public celebration of Mosaddeq’s life or his political accomplishments; that Iranians were not even allowed to gather at his resting place; and that of the three leaders of the NF in 1978, two had been assassinated by the Islamic regime’s agents (Shapur Bakhtiar in Paris in 1991 and Darius Forouhar in Tehran in 1998), and the third had died in exile (Karim Sanjabi). Other influential members of the National Front were executed, spent time in prison or, as in the case of Abdorrahman Boroumand (the author’s father), fell victim to the Islamic Republic’s assassins abroad. To this day, the NF is still banned in Iran.

The United States and the Shah were more lenient toward the NF than was the Islamic regime, which sought to murder their leaders and politically suppress their organization. It cannot be either the undemocratic nature of the coup or its ultimate political consequences—the elimination of Mosaddeq and his followers from Iran’s political life—that Iranian officials have in mind when they blame the US for the coup. For the regime itself has pursued similar outcomes through more violent means. The Islamic regime simply has used the coup as part of its propaganda and diplomacy, with the goal of misleading American policy makers.

Khomeini’s animosity toward the Shah and the United States traces back to 1963-64, when the Shah initiated sweeping social reforms that included granting women the right to vote and run for office and extending religious minorities’ political rights. These reforms prompted the pro-Shah cleric of 1953 to become his vocal critic. It wasn’t the Shah’s autocratic rule that incited Khomeini’s opposition, but rather the liberal nature of his autocratically implemented social reforms. In 1953, the traditionally quietist clerical establishment had united with proponents of political Islam against Mosaddeq and in support of the Shah; in 1963, they once again united, but this time against the Shah’s reforms. Khomeini was arrested after delivering a violent denunciation of the Shah. His supporters rioted, but his following was small, and the major ayatollahs did not support the riot. It was violently suppressed by the army on June 5-6, 1963 and Khomeini was subsequently exiled. It was during his exile that, to the dismay of the majority of Grand Ayatollahs, he concocted his heterodox theory of the direct political rule of the religious jurisconsult.

America’s Alleged Hostility Toward the Islamic Revolution

Khomeini’s enmity against the United States also cannot be attributed to U.S. behavior during the Islamic Revolution. Ayatollah Khomeini understood that U.S. human rights policy was crucial for the emergence of his movement in Iran. It was America’s friendly pressure on the Shah to liberalize his regime that had prompted the Shah’s government to authorize public memorial services for the passing away of Khomeini’s eldest son Mostafa on October 23, 1977. The movement that brought political Islam to power in Iran emerged during these memorial services, as they helped Khomeini become known to an ever-increasing number of people. These events were monitored by Savak (the Shah’s political police), whose reports reveal the impact of U.S. human rights policy on the development of revolutionary political Islam:

After Mostafa Khomeini passed … the government authorized memorial services during which religious students and preachers did and said what they wanted. A great number of religious students think that this freedom is due to Carter government pressure, because he is for freedom and says all people of the world must have freedom, and this, they [clerics] allege, is proven by the consecutive series of pardons granted to political prisoners.

Khomeini capitalized on his son’s passing and his own visibility from the memorial services, turning responses of condolence into calls for mobilization and unity among the clergy. He incited them to lead the movement at the expense of secular oppositionists:

Now that a temporary opportunity has arisen, the groups that are a hundred per cent committed to Islam … should… avail themselves of it. They should not allow the opportunists, who have not taken a single step or written a single word for Islam and the noble nation of Iran, to now use this opportunity to infiltrate the ranks of the suffering people by passing themselves off as patriots and freedom-lovers in order to attain ministerial and parliamentary positions.

The “opportunity” referred to by Ayatollah Khomeini is attributed, in a lengthy footnote, to the Carter administration’s pressure on the Shah’s regime to respect the human rights of Iranian citizens.

U.S. human rights policy became part of Iran’s internal political dynamic; its impact was neither accidental nor marginal. It was the main trigger of Iran’s social movement between 1976 and 1979. When on December 7, 1977, a number of dissidents founded the “Iranian Society for the Defense of Liberty and Human Right (CDHR),” they publicly acknowledged that their initiative was the outcome of U.S. human rights policy. This was the first self-proclaimed human rights organization in Iran, and most of its members later joined the revolutionary provisional government established by Ayatollah Khomeini in February, 1979. They regularly exchanged views with US diplomats; time and again, they asked the Americans to pressure the Shah and support their cause. American diplomats were listening, and although they did not always agree with their revolutionary interlocutors, they regularly warned the Iranian government against violent repression. Most crucially, U.S. diplomats warned Iranian army generals against any temptation to mount a coup, as reported by U.S. Ambassador William H. Sullivan on October 16, 1978:

I think we got across all three points: (A) no military coups; (B) no more censorship and (C) no resort to lethal force in handling potential popular disturbances. The resort to histrionics was, I believe, justified in the interests of making the message loud and clear. Sullivan.

Given the dependence of the Iranian army on U.S. advice, training, and technology, the ambassador’s guidance could not be dismissed by the Shah, who himself was averse to bloodshed, or by his generals. Seeking to prevent a military coup during the revolutionary period remained a constant of America’s Iran policy. More than a week before the Shah left Iran, the U.S. government sent General Robert E. Huyser, deputy chief of the European Command, to advise the army leadership during the difficult transition and to prevent the army’s disintegration in the absence of its commander-in-chief. Huyser strove to dissuade the army generals from staging a coup d’etat and overthrowing the newly appointed pro-democracy Prime Minister Shapur Bakhtiar. During his one-month mission, in January-February 1979, he strongly encouraged Iranian generals to support Bakhtiar’s government but also to negotiate and find common ground with Khomeini’s representatives.

General Huyser did not favor a revolutionary takeover by Khomeini; in this, he disagreed with Ambassador Sullivan, who had been advocating for a new anti-communist alliance that included the United States, the Iranian army, and proponents of Khomeini’s revolutionary Islam. In this alliance, there would be no room for an Iranian constitutional monarchy and, more generally, for liberal democracy. On February 4, 1979, a day before Ayatollah Khomeini appointed a revolutionary government in defiance of Bakhtiar’s constitutional government, Huyser’s mission was terminated at the insistence of Ambassador Sullivan.

Khomeini’s chosen Prime Minister, Mehdi Bazargan, had been one of the leading interlocutors of American diplomats during the revolutionary period (May 1978-February 1979). He and his friends had persistently advocated for U.S. support of revolutionary Islam against the communist threat. His appointment by Ayatollah Khomeini was reassuring to Ambassador Sullivan, who had been encouraging the army leaders to rally to the revolution, which they did on February 11, 1979.

The crucial role of the United States in the Iran crisis and the impact of its “advice” on the Iranian army command were best summarized by General Amir Hossein Rabii, Iran’s Imperial Air Force commander in chief, who played a determining role in the February 10th armed uprising that led to the fall of the constitutional government and later spoke at his trial:

He [General Huyser] … said ‘the Iranian people and the world don’t approve of autocracies anymore, and my government won’t support the Shah, he must go.’… We were dumbfounded, we said nothing.… his words, when he [Huyser] said the Shah must go, were a shock for me: how was it possible that an American general could say “the Shah must go … as if they were taking a mouse by its tail and throwing it out.… In the third meeting [with Huyser, after the Shah’s departure] he sat there and said, well the Shah is gone…; [General Philip C. Gast, chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) for Iran, who attended the meeting] left the room and came back with a paper with the phone numbers of the Imam’s representatives, and he gave it to us…. Then Huyser said: I think it is in the army’s interest to contact the Imam’s representatives…. What I understood was that Huyser had two objectives: either he wanted to lead the army toward the Imam’s delegates so that the army would rally to the revolution, or he wanted to use the army to bring Bakhtiar closer to the Imam’s delegates…

That is why Rabii had rallied to the revolution. What General Rabii was saying in his own defense before the revolutionary court (April 1979) is corroborated by General Huyser’s and Ambassador Sullivan’s reports to Washington.

There is no doubt that in 1979 the United States played a decisive role in preventing the army from launching a violent reaction against the revolutionary movement, just as it had played a determining role in 1953 in instigating the army’s action against Mosaddeq. Ayatollah Khomeini and his allies were well aware that they had benefited from U.S. influence. Ebrahim Yazdi, Khomeini’s personal emissary during his secret negotiations with the Carter administration in Paris, had, on January 15, 1979, asked the U.S. government to prevent a coup. He was assured by the American envoy, Warren Zimmerman, that the U.S. government opposed a military coup and had “no aspiration to dictate the policies of the Iranian government.” The empowering impact of such a candid revelation on the revolutionaries was fateful.

In the wake of the Shah’s departure, Amir Entezam, one of the embassy’s revolutionary contacts, thanked his American interlocutor “graciously and extensively for working with the military to prevent a blowup.” This was neither the first nor the last time that one of Khomeini’s followers thanked the U.S. government for restraining the Iranian army.

It is not accidental that on February 11 Ebrahim Yazdi was the man who came to the rescue of American military personnel assailed by a revolutionary mob in the Army’s headquarters. This is not how the enemies of the revolution were treated. If Ayatollah Khomeini and his lieutenants viewed the U.S. and its military advisers as enemies of the revolution, they would have arrested and expelled them from the country. In fact, as late as October 6, 1979, the Revolutionary authorities were still negotiating with their American counterparts for downscaled military assistance.

The case against America based on the 1953 coup and its efforts to hamper the victory of the Islamic Revolution unravels upon close scrutiny. Iran’s revolutionary authorities had been repeatedly assured that the U.S. government was seeking good relations with their new regime and that Iran’s “independence,” “stability,” “territorial integrity,” and “economic progress” were of “significant interest to the United States.” The revolutionary authorities had taken note of this American goodwill. They had even asked for American help in gathering intelligence about Afghanistan, Iraq, and Iran’s internal security situation. U.S. diplomats were doing their best to establish friendly relations with the revolutionary regime, and their efforts had not escaped Khomeini’s attention. As he was readying Iranians for a major confrontation with the United States, he ridiculed America’s new pro-Islamic Revolution stance.

Similarly, while the dying Shah’s short stay in a New York hospital may have worried uninformed young Islamist militants, it certainly did not seriously concern the Ayatollah and his government. On October 28, Khomeini publicly acknowledged that the hardly breathing monarch was no longer a danger.

Yet the official pretext for storming the U.S. Embassy, on November 4, 1979, was the American government’s authorization for the Shah to travel to New York. In reality, neither the dying Shah nor his wealth was the real cause of Khomeini’s ire. That is why the Shah’s departure from the U.S. and his death in July 1980 didn’t end the embassy occupation. Nor was the U.S. government’s inability to return the Shah’s personal wealth a serious enough obstacle to prevent Iran’s release of the American hostages in January 1981.

The Real Cause of the Storming of the U.S. Embassy

The history of the Islamic Revolution and the Islamic Republic is infused with disinformation. The momentous assault on the American embassy, which marked Iran’s exit from the Western alliance, is no exception. Initially, it appeared that the students who invaded the embassy had acted without the Ayatollah’s knowledge. But we now know that, on October 27, Khomeini’s representative to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) met with the young leftist cleric Musavi Khoeiniha, leader of the hostage takers, and the two men agreed on the embassy takeover. That same day the Commanding Council of the IRGC was instructed to provide logistical support for the operation. Although it was presented as a spontaneous initiative of the students, the hostage-taking had been pre-approved by Iran’s Supreme Leader and supported by the IRGC. On November 1, Khomeini publicly called on students to “demonstrate their power against America and Israel and force them to expel and handover the ousted criminal Shah.”

Khomeini wanted a confrontation with the United States, but his motive was neither to avenge the 1953 coup nor to preempt a non-existent hostile conspiracy in favor of the Shah. The occupation of the embassy had little to do with America’s deeds and much to do with the revolution’s needs.

The embassy takeover occurred at a time when Khomeini had not yet consolidated his totalitarian regime. Through a heavily rigged election he had convened an “Assembly of Experts” to draft a constitution. He had suspended press freedom, and was facing increasing social unrest. The united front that had brought him to power was unraveling. Outright rebellions were erupting in border regions populated with ethnic minorities. More crucially, the majority of Shi’a Grand Ayatollahs were strongly opposing the unorthodox and despotic constitution to which his Assembly of Experts was adding the finishing touches.

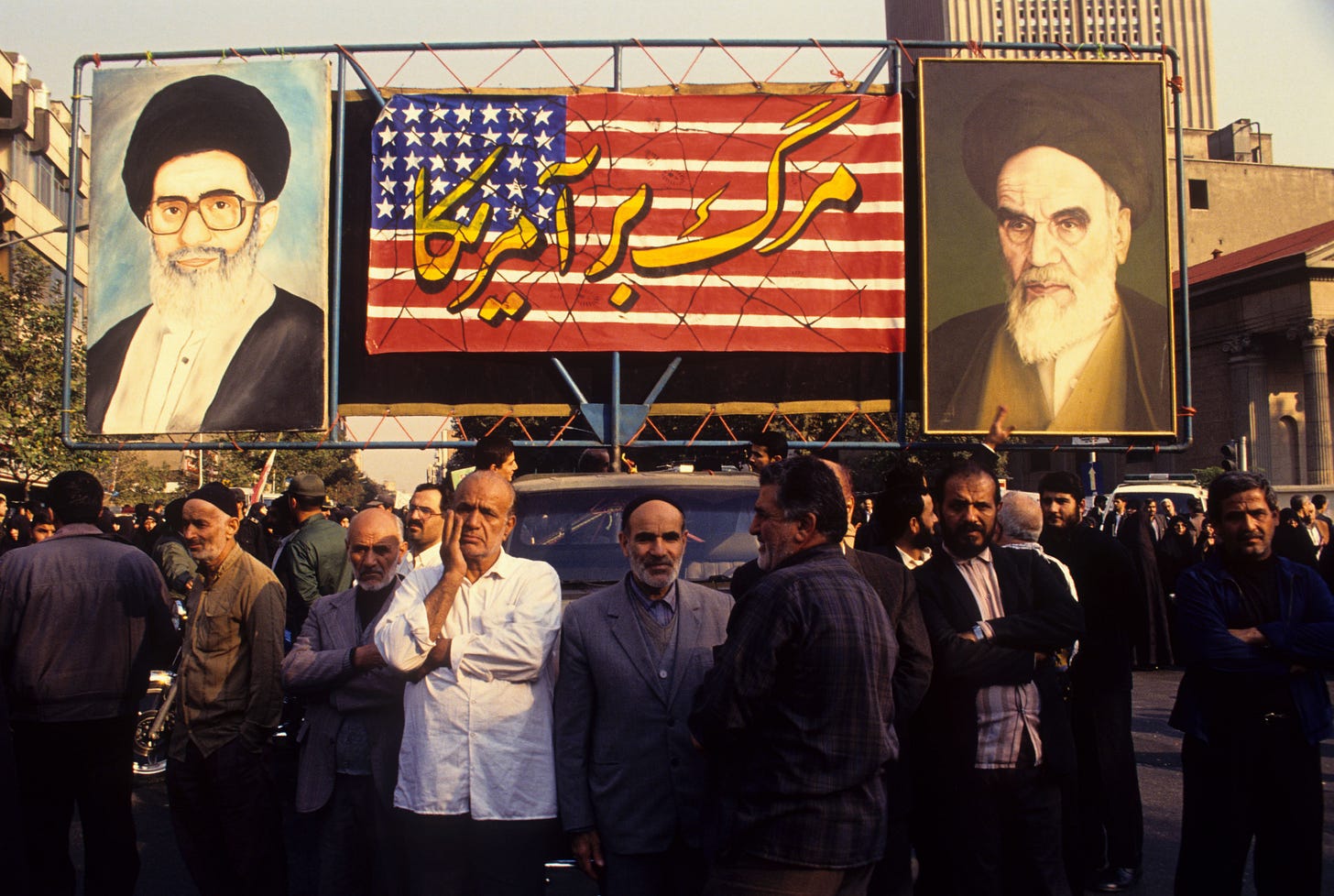

During September and October, as internal dissent was gaining momentum, Khomeini persistently stigmatized his critics as pro-Western and pro-American. “Your country will not be independent,” he told Iranians, “as long as your thoughts are not free…We must purge from our administration these rotten brains enamored with America and the West…” Khomeini also constantly spoke out against freedom of the press and freedom of expression. On November 5, in the wake of the assault on the US Embassy, he gave a decisive speech in which he described the United States as the Great Satan who had mustered “small Satans inside and outside Iran” against the Revolution. For the first time, adopting a formulation used by the Soviet press, he alluded to the US Embassy as a nest of spies.

In this critically important speech Khomeini declared that the storming of the embassy was the dawn of a greater revolution in Iran. The revolution, he said, will not “stand still and let them conspire… [only for us to discover] … the country is lost and we have been duped by nonsense such as democracy and the right of conspiring.” To delegitimize human rights, he branded them as the “right to conspire.” He defended all the summary executions that had been condemned by Western governments and media for their violation of due process and denial of defendants’ rights. He concluded by ordering the young people to continue their occupation without fear.

There is no need for particular interpretive skill to comprehend the substance of Khomeini’s message: as Satan, America embodies the temptation that seduces Iranian citizens into sin and falsehood. “Human rights” and “democracy” are America’s tools for luring sinful and deviant citizens into conspiring against the Government of God established by the Ayatollah. As a superpower embodying liberal democracy and promoting human rights, America becomes the Great Satan irrespective of its concrete policies toward Iran. The problem as viewed by Iran’s Islamist rulers is not what America does, but what America is.

Not surprisingly, the first casualty of the assault on the US embassy was the proto-liberal provisional government led by Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan who tried to promote the rule of law and defend due process. Bazargan’s transitional government resigned in the wake of the hostage-taking, and its resignation was accepted by Khomeini. For the hostage takers this resignation was the main victory of the embassy occupation.

During the 444 days of the hostage drama, Iranian authorities put forward many demands, most of which were not met. Their main goal was to gain time to checkmate their liberal (or rather proto-liberal) opposition. Forty years later a repentant hostage taker reflecting on the political meaning of their action confessed: “The embassy takeover… was the consequence of a leftist trend which spread the idea… that whoever is liberal and defends freedom and democracy is a gate opener for economic and political imperialism.”

With the hostage crisis, the Islamist regime was able to make anti-Americanism a central theme of the revolution. This induced Iranian Marxists to rally to its support and Moscow to extend its tacit protection to the new theocracy. Using the pretext of a vast American conspiracy, supposedly revealed by documents found in the American embassy, revolutionary cadres purged the government administration and the army, suppressed liberal democratic forces, and eliminated the Great Satan’s “democracy” and “human rights” from Iran’s public debate. Once they had strengthened their grip on their own society and felt secure in their new alliance with the Soviet Union, the Islamic revolutionaries let the hostages go and claimed victory over the Great Satan.

The release of the hostages did not change the Islamic regime’s hostile attitude toward the United States, as it did not alter the nature of the American polity, which still embodies liberalism in the eyes of Iranian leaders. When the new constitution was challenged in the name of the people’s sovereignty by Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari, Khomeini accused him of promoting “an American Islam,” defrocked him, and kept him under house arrest. Years later, when clerics opposing political Islam and favoring religious freedom and tolerance dubbed their viewpoint “merciful Islam,” Khomeini’s successor Ayatollah Khamenei tried to discredit this movement by associating it with America. For Iran’s Supreme Leader, “merciful Islam” is imbued with “American values,” notions rooted in liberalism, and ideas consecrated in the “Declaration of Independence” and promoted by “George Washington, his acolytes, and successors.” Ever since November 1979, any protest, dissidence, uprising, armed rebellion, peaceful protest, or civil disobedience has been denounced as a product of American conspiracy.

Over the last forty-five years, the histories of the United States and Iran have been intertwined in a strange way. The story of Iranian civil society’s fight for freedom is also the story of how America has been inadvertently drawn into this struggle. An ever-growing number of Iranian citizens are being tempted by the Great Satan’s seductive concepts of “democracy” and “human rights,” as recently and spectacularly demonstrated by the Woman Life Freedom movement. Nothing illustrates this entanglement better than the two clashing slogans. One is “Death to America,” chanted at government rallies and echoed in Parliament during the inauguration of Masud Pezeshkian, the new President of the Islamic Republic. The other, responding to it and chanted by anti-government protesters since December 2017, is: “Our enemy is here; they lie when they say it is America.”

In January 1981, the American hostages were released, but America remained—and still remains—a hostage in the Islamic regime’s war on its own people and their democratic aspirations. This was the initial battle in a broader conflict with liberal democracy. It is not a military or economic struggle; its essence is ideological.

When deciding on new economic sanctions or military strategies, American decision-makers remain in their cultural and intellectual comfort zone. This is what they know how to do, and they continue to do it regardless of the nature of the enemies they have faced over the years. The failure of their 45-year efforts to change the Islamic regime’s behavior is a testament to the inadequacy of this approach. America and the liberal West, in general, cannot evade the challenges posed by Islamist ideology, for it is subverting democracy even within their own societies. Crafting an ideological counter-offensive, which requires a deep understanding of Islamist ideology, is where their creative focus should lie.

Dr. Ladan Boroumand, a former Reagan-Fascell Fellow at the International Forum for Democratic Studies, is the co-founder of Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for the Promotion of Human Rights and Democracy in Iran (ABC).

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below: