Why I Didn’t Apologize For That Yale Law School Email

We must end the culture of performative repentance.

I could go back to studying for my classes. I could stop the seemingly endless meetings with Yale administrators. And I could save my legal career—a future that now seemed in jeopardy.

All I had to do was apologize.

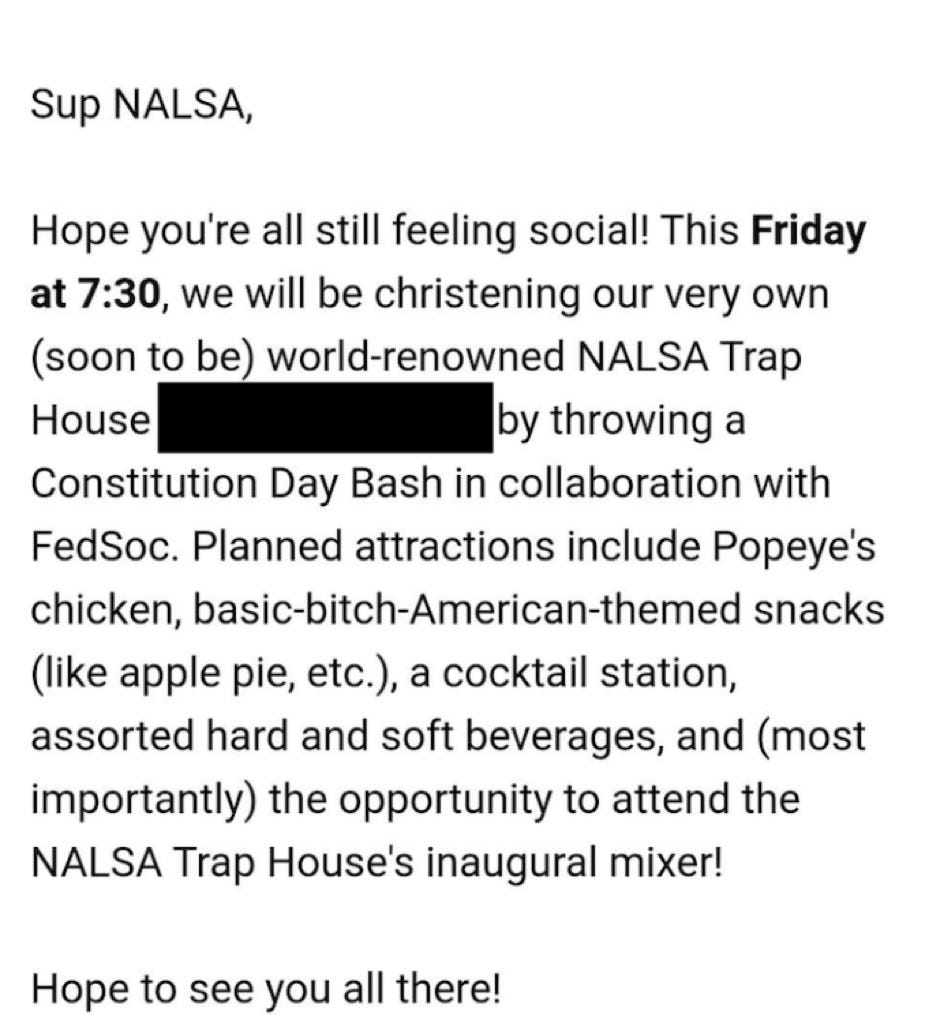

The problems began last month when I sent the following email inviting fellow members of the Native American Law Students Association to a party co-hosted with the Federalist Society, a conservative and libertarian student organization.

Within minutes, someone sent a screenshot of my email to a class-wide forum where several students denounced the message as racist. In no time, people were calling for an apology.

At first, I was unsure what I was being asked to apologize for. I became even more baffled when I was told that my use of the term “trap house” indicated “inherently anti-Black sentiment.” As a Gen-Zer, I’ve always known “trap house” to be synonymous with “party house.” The top entry for “traphouse” on Urban Dictionary matches exactly what I meant—“Originally used to describe a crack house in a shady neighborhood, the word has since been abused by high school students who like to pretend they’re cool by drinking their mom’s beer together and saying they’re part of a ‘traphouse.’”

The popular understanding of “traphouse” in no way suggests it is a racial slur. If the usage of the term alone is offensive, why have the hosts of Chapo Trap House, the incredibly popular podcast which self-identifies as radically left-wing, not been asked to apologize for the same reason?

Barely twelve hours after I sent the invitation, two discrimination and harassment resource coordinators from the Law School’s Office of Student Affairs scheduled a meeting with me. In that discussion, Ellen Cosgrove, the Associate Dean, and Yaseen Eldik, the Director of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, repeatedly urged me to issue a public apology.

I told them I did not want to send out a generic statement and would rather have individual conversations with anybody offended. I was told that things might “escalate” if I failed to apologize. I was told that an apology would be more likely to make the situation “go away,” and it was implied that there would be lingering impacts to my reputation because the “legal community is a small one.” The subtext behind the meetings that followed became increasingly clear: Apologize or risk the consequences.

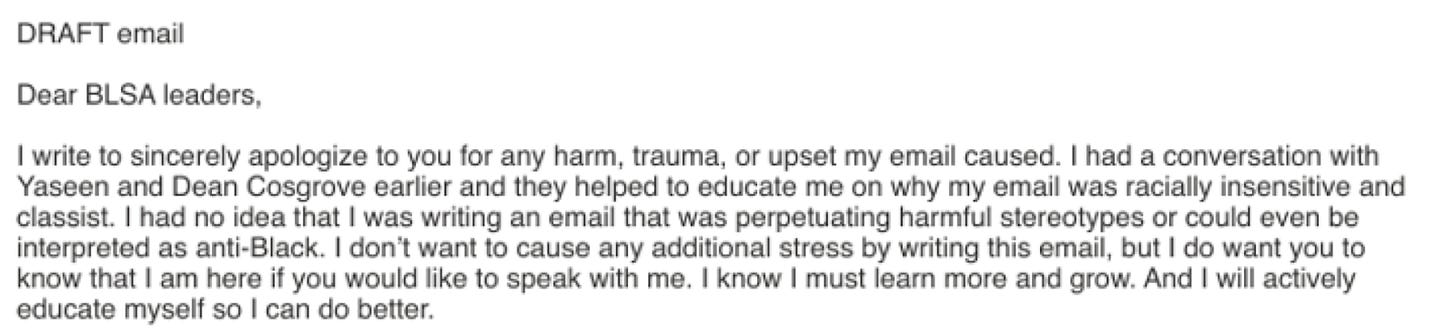

They even went so far as to draft an apology for me directed to the Black Law Students Association (see below), which I declined to use.

Cosgrove and Eldik called me later that night and yet again pressed me to sign their pre-drafted apology, despite my repeated attempts to explain that I was not comfortable doing so. I was in the middle of telling them why I was against a public statement when—while they were still on the phone with me—an email was sent to Yale Law’s entire second-year class “condemn[ing] in the strongest possible terms” the “pejorative and racist language” in the invitation.

Rather than insincerely sign on to words that weren’t even my own, I decided to return to the forum where this all began. I clarified the intent of my language and said I would welcome the opportunity to speak to anyone offended by my original email.

For the Yale administrators, this “fell short.”

I should clarify that I am not by nature someone who is against saying sorry. I have no problem apologizing for an action, even if I didn’t intend harm. But not every instance where an apology is demanded is one where it is actually warranted.

After all, a fellow student wrote in our class forum that my failure to apologize was “corny.” If I had interpreted the usage of “corny” to be a sly reference to my indigenous background (corn is a Native American crop with immense cultural significance in indigenous communities), should that student be forced to apologize to me? I believe most people, including that student, would say no. An action does not warrant a forced apology just because an individual or a group demands it.

Instead, an apology should be a sincere expression of remorse and admission of fault. The Yale administrators did not believe I had been racist by using the phrase “trap house.” But it did not matter. They urged me to placate students via public submission.

I don’t believe that the now-common ritual of compelled apology, complete with promises to “grow” and “do better” (their words, but ones I’m sure you’ve seen many times before) helps anyone, or is even intended to. If we continue to indulge this culture of performative denunciation, the very idea of an apology will lose its meaning.

It might be tempting to view my story as one about conservatives being discriminated against and prevented from sharing ideas freely in elite educational spaces. After all, Eldik explicitly identified my “association with FedSoc” as an especially “triggering” factor for students. But I believe this diminishes the full significance of what happened.

The important questions are about the wider culture that made the administration's intervention possible in the first place. Before they ever step inside a classroom to learn torts or contracts, first-year students are required to attend diversity and inclusion training which teaches us to see racism all around us in the form of microaggressions and implicit bias, prioritize lived experience, and engage in the confessional sacrament of acknowledging one’s privilege.

The Black Law Students Association President wrote in a recent email that calling someone out “is not an act of oppression; it is an act of love and compassion.” But calling people out at Yale Law School goes further than just informing others of an action that may have caused offense. Here, calling people out means relentlessly demanding the offender admit fault and beg for forgiveness—as my experience shows, this pressure comes from students and administrators alike.

Our most prominent student organizations are affinity groups defined primarily by racial identities. As a member of the Native American Law Students Association, I appreciate the importance of cultural heritage, but obsessing over race as our primary organizing principle is unhealthy and divisive. It should not infuse our perceptions of the world to the degree it does.

Yale Law School is one of the most powerful institutions in our society. Those who care about the future of the country should care about the kind of students that it and schools like it are producing. My own experience has been frustrating, but it would not be so important if not for what it reveals about our institutions more broadly. I hope this serves as a wake-up call for Yale to make a concrete commitment to the virtues of rigorous enquiry and open-mindedness it espouses.

Trent Colbert is a second-year student at Yale Law School.

Appreciate the piece and the author's steadfastness.

The part about the "two discrimination and harassment resource coordinators from the Law School’s Office of Student Affairs" swiftly stepping in and trying to justify their jobs is particularly telling of what the liberal humanist camp is up against.

In not apologizing, you acted honorably; no one should have to apologize publicly just to appease the crowd. I am baffled that this happened at a law school, of all places. Doesn't law school emphasize the principles of "innocent until proven guilty" and not having to testify against yourself?