Colleges Are Surrendering to AI

Here’s a better strategy for equipping students for the age of artificial intelligence.

We are at that strange stage in the adoption curve of a revolutionary technology at which two seemingly contradictory things are true at the same time: It has become clear that artificial intelligence will transform the world. And the technology’s immediate impact is still sufficiently small that it just about remains possible to pretend that this won’t be the case.

Nowhere is that more clear than on college campuses.

The vast majority of assignments that were traditionally used to assess—and, more importantly, challenge—students can now easily be outsourced to ChatGPT. This is true for the essay, the most classic assignment students complete in humanities and social science courses. While the best students can still outperform AI models, a combination of technological progress and rampant grade inflation means that students who are content with an A- or perhaps a B+ can safely cheat their way to graduation, even at top universities.

Something similar holds true for the dominant mode of assessment in many science courses. If anything, AI models that have won top marks in math and science olympiads may be even better at answering the questions contained in problem sets in biology, chemistry, physics or computer sciences classes.

For the most part, professors have responded to this problem by ignoring it.

Some are in outright denial: Many academics and writers have convinced themselves that the real flaws from which chatbots still suffer, such as their tendency to hallucinate, make them far less competent than they actually are at fulfilling a wide range of academic tasks. Even as a significant proportion of their students are submitting AI-generated work, they proudly reassure each other that their courses are too demanding or too humanistic for any machine to understand them.

Others are well-aware of the problem but don’t really know what to do about it. When you suspect that an assignment was completed by AI, it’s very hard to prove that without a confrontation with a student that is certain to be deeply awkward, and may even inspire a formal complaint. And if somehow you do manage to prove that a student has cheated, a long and frustrating bureaucratic process awaits—at the end of which, college administrators may impose an extremely lenient punishment or instruct professors to turn a blind eye.

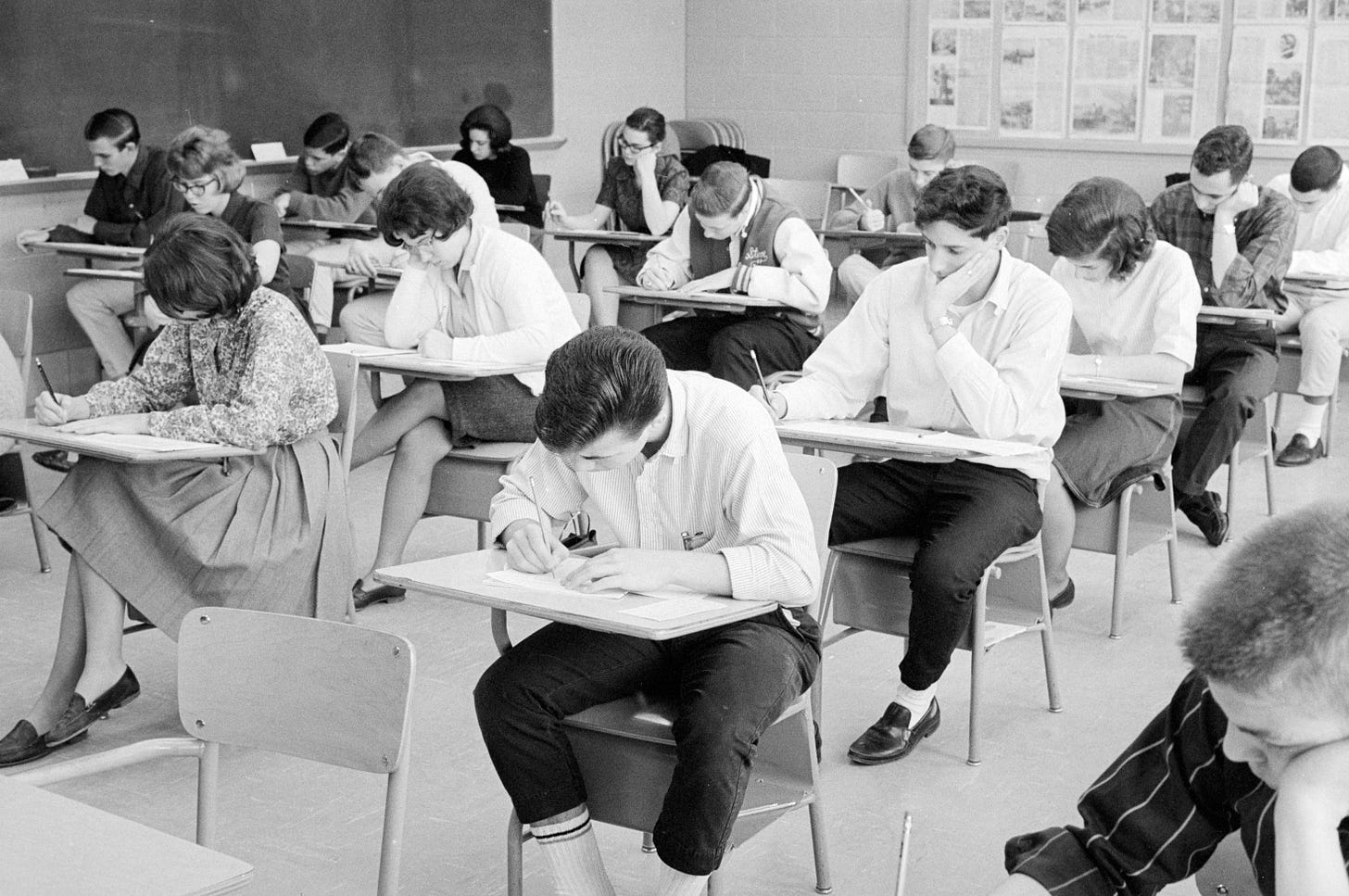

Alternative forms of assessment may be a way out. But oral interrogations and in-person exams with pen-and-paper have gone out of fashion. They are likely to inspire the ire of students—and in any case require a lot more effort to administer. So even for those who are conscious of the problem, the path of least resistance remains pretending that it doesn’t exist.

An old Soviet joke held that “we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us.” At many colleges today, students merely pretend to do their academic work. For now, most professors still diligently read and comment upon the efforts of ChatGPT; but I suspect that some of them will increasingly decide to outsource their grading to artificial intelligence as well. Campuses will then have reached a new stage of AI decadence: the students pretend to do their assignments, and the professors pretend to grade them.

Denial won’t, however, be an option forever.

Over the next years, the technology will continue to advance. Students who have used AI tools throughout their high school careers will start to arrive on campus. They will be much more skilled at using those tools to complete traditional assignments. They may even become adept at accomplishing genuinely impressive things with the aid of these new tools. The pretense that current forms of assignment are meaningful, or that a college GPA gives employers a meaningful signal about candidate quality, will become untenable. At the same time, some of the basic skills students need to master to truly understand their chosen disciplines—or merely become fully-formed citizens capable of reasoning carefully about the world—will rapidly atrophy.

What should colleges do in response? Is the right path a full embrace of AI tools or a much more radical set of precautions against their widespread use?

The answer, I have increasingly come to think, is: Both.

Anybody who wants to make a genuine contribution in the future, whether in the workplace or even in academic research, will likely need to be fluent in exploiting AI tools. It is thus the task of universities to teach students how to make the most full and creative use of these tools, something many of them currently fail to do.

But even in a world in which AI tools become ever more powerful and widespread, basic skills like clear thinking and strong writing will remain extremely important. And this means that the ease with which AI tools can help students evade ever having to do the hard work that is required to pick up these skills is a genuine threat to their intellectual growth.

Writing essays may feel like a deeply artificial exercise. And of course we are entering a world in which many of the writing tasks that were once involved in white-collar work, from email to business plans to PowerPoint presentations, can be outsourced to AI just as easily as college assignments. Some will be tempted to conclude that academic skills that were once very important, like the ability to write, have lost their significance.

But this ignores a point I have stressed to my students since long before the release of capable AI models: Writing is thinking. When we talk, it is easy to be vague about ideas we don’t fully comprehend, or to skip a few logical steps. The moment you try to commit an argument to paper, such weaknesses are mercilessly exposed. (Indeed, that is why I don’t really believe that people are being honest with themselves when they claim that they are merely bad writers: for the most part, people who are bad writers are bad at writing because they haven’t taken the effort to think through their own ideas.)

If you want to be a successful artist today, you will probably spend little of your time etching still lifes or producing work that involves challenging problems of perspective; but for the most part, art schools still recognize that mastering those skills is a necessary part of your education. Something similar holds for skills, like writing, that could in theory be outsourced to ChatGPT: While you may not need to call on them directly once you graduate, mastering them will give you the skills and habits that will make you much better able to understand the world and act in it.

This is why universities need to put more emphasis than we currently do on both basic skills and on the use of new technologies. The students best able to make a contribution in the future are those who have both been forced to write plenty of traditional essays without the use of digital tools and who are skilled in using AI to push the boundaries of human knowledge

At the moment, universities are choosing a dangerous middle path: they are persisting with old forms of assessment as though they remained meaningful, without leaning into the potential that comes from calling upon the prodigious powers of AI. Instead, they should bifurcate different forms of assessment: In some courses and contexts, students must be forced to prove their intellectual mettle without the use of digital tools. In other courses and contexts, they should be given the knowledge and the knowhow to use these tools to the best effect.

This is what I myself hope to experiment with when I teach two undergraduate seminars at my university, Johns Hopkins, next term. For the first time since I started teaching at the university, I will administer an in-person exam that students need to complete on pen-and-paper. They will have three hours to write three essays about the broad themes of the course, demonstrating their mastery of the material and their ability to make a compelling argument without any outside assistance. But for their final research paper that is the capstone of any demanding undergraduate seminar, I will encourage them to use AI liberally. While they will need to acknowledge and document the exact ways in which they use AI to assist them with that project, I will assess the final product exclusively on whether it makes a meaningful intellectual contribution.

The most skilled pilots are both capable of flying a simple Cessna that contains little technology and of handling the myriad gadgets contained in a Boeing 787. Similarly, the best-prepared workers and scholars and citizens of the future will both be capable of thinking for themselves without the help of ChatGPT and of expertlyly calling upon the help of such magician’s apprentices when appropriate. Our task as their teachers is to help them accomplish both.

This essay grew out of a short contribution to a forum on AI and education in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Yascha - it occurred to me while reading your piece that one way to assess students' thinking in the age of AI might be to assess a transcript of their interrogation of ChatGPT's responses on a topic, following a kind of Socratic method. I wonder if there is a way to do this that prevents the students using another AI to represent "their half" of the discussion? Perhaps not. But I imagine it would require your students to argue from multiple perspectives in order to sustain the 'debate' and expose flaws and assumptions in the GPT response. You could require students to enter a specific, standardised set of prompts that set up not only the question or topic for discussion, but what the objective of the exchange is, what the role of the student and of the AI will be, whether either or both can cite research, etc. Just an idea.