Why Salman Rushdie Is Unable to Live or Die in Peace

My quiet revenge on the mediocrities who would silence genius.

Last month, I found myself reading Salman Rushdie as an act of defiance.

It had been another trying week, when every story in the news seemed to take the form of mediocrities trampling on their superiors in one form or another. RFK purging vaccine experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ABC News suspending Terry Moran for calling the sky blue. The Attorney General punishing government lawyers for telling the truth in court.

Such is populism; such are the times.

I like to think I am beyond provocation. I’ve developed the copes it takes to register each humiliation but still function. We’ve all had to, haven’t we? I’ll look away and count to ten. I’ll pet my cat. I’ll take a slow walk.

The copes work, until they don’t.

Now and again I’ll read something that overwhelms them. It’s not always the biggest stories. Some can be quite small, at least for me. Certainly, in the scheme of things, the story that ruined my day on May 14 was small.

“Salman Rushdie pulls out as commencement speaker at California college over protest threats,” the headline read.

I clicked through. It was a mistake.

Soon, I learned that the Muslim Student Association at Claremont McKenna College was displeased with the administration’s decision to invite Rushdie. In the ossified, cut-and-paste rhetoric of the woke scold, the MSA called on students to speak out against “platforming individuals who have deeply offended marginalized communities.” Student activists condemned what they characterized as his “disparaging comments about Palestinians.”

Rushdie, perhaps calculating he’s given as many eyes as it’s reasonable to give in defense of freedom of speech, withdrew his offer to speak.

I felt a hot rush of fury flashing through my body, a physical, palpable rage.

Rushdie.

These motherfuckers silenced Salman freakin’ Rushdie.

In 2025!

For the next few hours, I only saw red. None of my copes would cope. The walk around my neighborhood left me in exactly the same mood as when I started. I came home and opened a bottle of wine; that didn’t help either. Rage gave way to sadness: a disgust with the world. I didn’t know what to do.

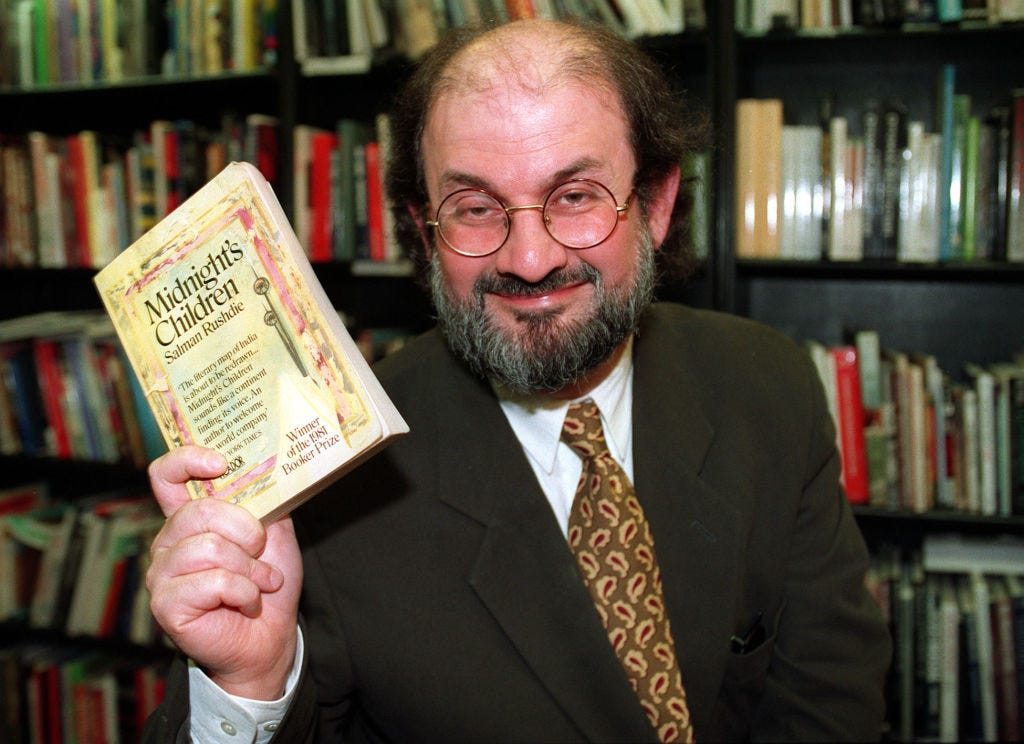

Then I noticed my old copy of Midnight’s Children sitting quietly on a high bookshelf. I reflected on how many boxes it had traveled in as I moved from house to house over the decades. I had read it long ago, in the ‘90s, when I was a teenager. Probably around the same age as the Claremont McKenna brutes now silencing its author. I remembered being dazzled by it, but I also remembered sensing I understood only a fraction of it.

Then it hit me. I can just read it again. Nobody can stop me.

I took it down from the shelf, paged through it, taking in that characteristic smell of a neglected paperback. Then I cracked it open: “I was born in the city of Bombay … once upon a time. No, that won’t do, there’s no getting away from the date…”

It was the only good decision I made that day.

Midnight’s Children is a hard book to summarize, categorize, or even describe. It’s a mad riot of the imagination, a book so full of life it seems to spill out in all directions. The narrator, Saleem Sinai, is born in what was not yet Mumbai at the precise instant when India and Pakistan became both independent and separate. As a boy, Saleem discovers he has mysterious powers that link him metacosmically with the nation of his birth, and with all the other children born in that first hour after independence, children who also have powers they can’t explain. Saleem gradually realizes his birth left him “handcuffed to history.” He’s doomed to run, Forrest Gump-style, through every significant event in his young nation’s life: its purpose becoming his purpose, its crimes his crimes.

To pull off this narrative feat, Rushdie cribs liberally from everything and everyone, Proust and Bollywood, García Márquez and cheap radio soap operas, Tristram Shandy and Superman comics, throwing it all together in a mad literary jumble that’s sexy and sensuous and funny and smelly and bonkers and really, really shouldn’t work but holy shit does it work.

You could say all that and plenty more, but you’d still be nowhere near doing Midnight’s Children justice. Because it’s a masterpiece. And the only way to do justice to a masterpiece is by reading it.

The Rushdie who comes through those pages is in every way different from the Grand Old Man of Letters we’ve come to think of him as: “a young, unsuccessful writer wrestling with an enormous and still intractable story.” Not yet 30 and living in obscurity in a flat in a rough part of London, the Rushdie of Midnight’s Children is Rushdie before the Booker Prizes, before the fatwa, before life in hiding, before knife-wielding maniacs: a straight-up genius nobody had ever heard of.

As I waded deeper and deeper into Saleem Sinai’s life, as I gave in to the trance Rushdie weaves for us, my rage subsided. There is too much going on in these pages to stay angry at some clueless college kids in California.

Gradually, my rage at the SJWs of that Muslim Student Association gave way to something like… pity? A sort of sorrow that they don’t know Saleem Sinai, that they live in ignorance of his nose and his pickles. That their tiny little closed minds have no space in them for the explosion of life on Salman Rushdie’s pages. That the desiccated certainties of their cheerless ideology have no place for Mary Pereira’s chutneys, that their constricted little imaginations can’t conceive of the grand imperative Saleem ultimately accepts as his duty in life: the pickling (yes, the pickling) of all of India. Unable to see an inch beyond their claustrophobic ideological blinders, they do violence to themselves, missing the genius entirely and treating Rushdie as a sort of walking position paper, a bundle of problematic views about Palestinians and Islam, nothing more.

Still and all, they did silence him. In 2025, mediocrity will never miss a chance to humiliate genius.

But genius is still genius. And just as it’s in the nature of mediocrity to stare straight at genius without noticing it, it’s in the nature of genius to labor under that invisibility every single day.

But then, none of this will be news to Salman Rushdie.

He’s known it all along. In a premonitory vision at the very end of a book stuffed to the gills with premonitory visions, Rushdie closes Midnight’s Children with a road map to the second half of his own life:

“Yes, they will trample me underfoot,” Saleem says,

the numbers marching one two three, four hundred million five hundred six, reducing me to specks of voiceless dust … because it is the privilege and the curse of midnight’s children to be both masters and victims of their times, to forsake privacy and be sucked into the annihilating whirlpool of the multitudes, and to be unable to live or die in peace.

Quico Toro is Director of Climate Repair at the Anthropocene Institute, a contributing editor at Persuasion, and writes the Substack One Percent Brighter.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Thank you for this tribute to a great man and a great writer. Midnight’s Children is important, not least for perspective of Indian Muslims who opposed partition and trusted in secular democracy of Congress party which Modi is now betraying. I was appalled by cowardice of Nobel Committee who chose to honor an unremarkable French feminist the year following attempted assassination of Rushdie

> Rushdie, perhaps calculating he’s given as many eyes as it’s reasonable to give in defense of freedom of speech, withdrew his offer to speak.

Yes. Heroism has it's limits. But how do we cancel the cancelers without resorting to their tactics?