Wisdom from the Bloodlands

Zbigniew Brzezinski embodied the perspective of Central Europe–and captured a reality that the West ignores at its own peril.

Editor’s Note: The following remarks are adapted from a speech delivered for the Zbigniew Brzezinski Memorial Lecture at the College of Europe, January 22, 2024.

While we recognize Zbigniew Brzezinski and his student Madeleine Albright as leading thinkers in their field, both of whom saw the fundamental importance of democracy as the basis of security for the West and indeed the world, it is all too telling that these two giants of foreign policy, who are both from the part of Europe I come from—Central and Eastern Europe—had a broader vision, as well as a more profound effect on our continent and relations between Europe and the United States, than almost any other European of the past fifty years.

Indeed, it is more than odd that even today, more than a third of a century after the liberation of Central and Eastern Europe, it is our region—the region that gave Brzezinski and Albright their understanding of the Soviet Union, of Russia, and of the importance of human rights and democracy—that has almost no impact on our continent’s foreign policy and security thinking. But two of the giants of the primary guarantor of European security come from areas subjugated and devastated by wars between East and West, wars in which we played almost exclusively the role of the victim.

Our part of Europe—the Zwischenländer—the “lands in between,” have been the contested lands or die umkämpften Ländereien for more than a millenium. Or, to use Professor Timothy Snyder’s depressing but all too apt name, they are the Bloodlands.

Smaller than the lands to our east and our west, our part of Europe has been caught between Homer’s two great sea monsters, Scylla and Charybdis. Only careful navigation by Odysseus between the crashing rocks and the whirlpool of death allowed him to survive to reach his beloved Penelope. And so too, in this century our own various leaders has occasionally allowed us to escape death and disaster on our road to our democracy.

The Melian Archipelago

One of the few non-trivial truths of international affairs we learned already 2500 years ago, from Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War, in his conclusion on the subjugation and destruction of the people of the Greek island Melos, a small island invaded by Athens. Its inhabitants appealed to law and their treaties to say the Athenian occupation and subjugation of Melos was illegal and unjust. The Athenians would have none of it. They deported and made slaves of the women and children of Melos. Its men were slaughtered. Thucydides concludes from this: The strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must.

In Thucydidean terms, Central and Eastern Europe can be best characterized as a Melian Archipelago. We are a stretch of small and weak states that have had to submit to the more powerful, and often suffered horrific destruction from the Scylla in the west and Charybdis in the east. Indeed, we modern day Melians have had too much of suffering what we must and our neighbors doing what they will. Therefore, in the third of a century since the democracy revolutions of 1989-91, we have placed at the core of our policies the resolution that never again will we allow ourselves to suffer the fate of our mothers, our fathers, and our ancestors stretching back a thousand years.

This too is why we take what too many consider just a cliché—the rules-based international order—far more seriously than others. Yes, we know the fate of the Melians and what resulted from their having put their faith in treaties and agreements. But what else can we appeal to? For too many to the west of us, it’s a cute cliché as well, a cliché that falls victim to self-interested so-called realism or realpolitik. But it is why for us, the rules-based European Union and NATO are of such vital importance.

The Melian tragedy is repeating today right before our eyes in Ukraine. Agreements are not kept, the strong do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must. Tellingly, I think Brzezinski would point out, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (with the exception of the one country faltering in democracy) are the ones who try the most to help a fellow victim. We see this in the percentages of GDP of military assistance given by Poland and the Baltic States, as well as the percentage of our own populations of the number of Ukrainian refugees we have taken in. To say that the task Europe faces in assisting our fellow Melian islander, Ukraine, is daunting, is a massive understatement. While to our west we see Scylla dithering as Ukraine is sucked into the whirlpool, we know full well what will happen if we lose Ukraine from the swath of democracies running from Estonia down to Slovenia.

Brzezinski, in one of his most classically prescient aphorisms, captured the challenge:“Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire, but with Ukraine suborned and then subordinated, Russia automatically becomes an empire.”

Let us unpack that a bit. What is Russia if it is no longer an empire? A large but pitifully corrupt developing country, Burkina Faso with rockets (to update Xan Smiley’s characterization of the Soviet Union’s erstwhile ally, Upper Volta). Or, “a gas station masquerading as a country,” to quote the late Senator John McCain.

But as an empire Russia means a country with imperial ambitions. Thinking of itself as an empire, Russia will view the loss of its colonies not as phantom limb pain, but as prosthetics to gather up after temporarily losing them. The almost daily rhetoric of the Russian leadership extols the country as an empire, in addition to Nazi-era genocidal threats. Only last week, Putin spoke of restoring old lands. A billboard in Moscow proclaims Russia knows no borders. That poster was put up already a month ago on the Russian side of the Narva River, facing Estonia.

Brzezinski’s quote on Russia as an empire if it includes Ukraine dates from 2012, twelve years ago. He could already then sense the way Russia was headed under Putin, and knew that with democracy increasingly stifled and autocracy growing stronger, how different Ukraine from Russia was becoming, even under the Yanukovych regime and already before the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Brzezinski saw where the increasingly Western and democratic country was moving.

Ukraine as a nation-state is gaining a deeper emotional commitment from a younger generation—whether primarily Ukrainian or Russian-speaking—that increasing views Ukrainian statehood as normal and as part of its identity. Hence time may not be working in favor of a voluntary submission of Kyiv to Moscow, but impatient Russian pressures to that end as well as the West’s indifference could generate a potentially explosive situation on the very edge of the European Union.

The difference between Russia as empire and Russia as just a large country is probably the most fundamental insight into the challenge facing European security since World War II. Had Ukraine been an independent country in 1945, most of Central and Eastern Europe would have been free far earlier. The Soviet Union as the reconstituted Russian Empire was the primary threat to European security until its collapse, subjugating both its inner empire of so-called republics as well as its outer empire of colonies.

Personally, I would say Brzezinski’s insight is historically even more profound. And it’s grounded in realism, if you will. It goes back to 1709 when Karl XII of Sweden, no friend of Poland I should add, lost the battle of where…? Yes, Poltava … in Ukraine. This was the beginning of the Russian Empire, formally in 1721, which inter alia resulted in the annexation of Estonia, Livonia, and Ingria, the Finnic lands around the Gulf of Finland, and, as a result of the Fredrikshamn Treaty, the incorporation of Finland itself, in 1809.

The challenge of European security since the 18th century, and since 1848 the challenge also to the idea of a liberal Europe, has been Russia as empire. The credo of Russian rule then, as it regrettably remains today under Putin as it was when formulated by Nicholas I, is “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationalism,” Pravoslávie, samoderzhávie, naródnost'. A melding of dictatorship, nationalism, and theocracy. It’s a bad mix—only look at Iran.

A Continent of Exiles

Thirty-five years ago in 1990, I began writing an essay titled A Continent of Exiles after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It turned out to be an incredibly naïve idea on how, now that Central Europe—Poland, Hungary, and the erstwhile Czechoslovakia—had regained their freedom, the West would finally learn that the exiles from those countries, from Prague in 1968, Budapest in 1956, and the dozen or so other formerly communist countries, had been right. I thought that once people heard what the victims in our countries with an immediate and contemporary experience of dictatorship said, we would find vindication for what the refugees had been warning about.

What a naïve belief. Fortunately, Estonia’s own liberation movement had become so red hot I had no time to finish that essay. Thank God. For what I soon discovered was that it was no longer merely the voices of exiles but the empirical experiences of Central and Eastern Europeans themselves that were denigrated, as if they, too, were Exiles With Their Hair On Fire.

Brzezinski knew this all too well. “Who’d trust a Pole for advice on Russia?” was how Averell Harriman (once considered the doyen of American experts on Russia) characterized Brzezinski. What Harriman was saying and what we have been hearing ever since 1989 in reality was, don’t trust what people who actually know what they are talking about and have experience of are saying. Listen to what we say, not them. Indeed, as we can attest, they did not listen to us.

I suppose it must have been especially galling for Brzezinski to be at Columbia’s Harriman Institute, a leading center for the study of Russia and Eastern and Central Europe. Frankly, I think my alma mater should change the name.

But the attitude was and remains widespread. It’s an attitude toward Eastern and Central Europe that is both arrogant and Orientalist, to use the term coined by another Columbia scholar, Edward Said, to characterize the haughty and contemptuous view of the West toward the East. Said wrote of the way Western academics treated what used to be called the Orient. Yet it applies equally to Central and Eastern Europe.

As Mary Sarotte recounts in her book about NATO’s eastward enlargement, Not One Inch, as early as March 1990—a mere four months after the fall of the Wall—a senior Austrian official told Undersecretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger why his country had suddenly reversed policy and had applied to join the European Community. “We have to get in before the Swamp,” were his words.

It’s a widespread attitude, affecting not only policymakers but the general public as well. When my bicycle was stolen in 1991 in Munich, I told my apartment house’s Hausmeister. Her answer was Kaum gestolen, Morgen in Polen. Stolen today, in Poland tomorrow.

We now know from the Helmut Kohl memos published in Der Spiegel in 2022 that in 1990 the German chancellor was opposed to the re-establishment of independence for the Baltic States. An interesting position from the leader of a country whose earlier chancellor had instigated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact dividing Eastern Europe between Germany and Russia, allowing the occupation by the Soviets of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. So much for the much-vaunted policy of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, that is the official German policy of dealing with its past. After we nonetheless declared our independence, despite his opposition, Kohl also bitterly opposed both EU and NATO membership for the Baltic States.

We all know this stance. We know how no one listened to what we said; how the frontline Baltic States were the only ones not to get contingency plans in NATO, that is, the planning needed in case we were invaded. Belgium, Canada, and Portugal all had NATO plans drawn up just in case. But not those countries most threatened. After all, it might have offended Russia.

We know how after the invasion of Georgia, the president of Finland, when asked why her country did not protest when Estonia did, replied, “Finland is the easternmost Nordic country, not the northernmost Baltic country.” She followed that up, for some reason, with saying that the Estonians protested because “they suffer from a Post-Soviet Traumatic Stress Syndrome.”

We know too, how after the Georgia invasion Nicolas Sarkozy, then president of France, pushed through the restoration of Russia’s Partnership and Co-operation Agreement even though it had not met the agreed-upon troop withdrawal as a condition for the PCA. Nor has it to this day. And we can recall how the United States in 2009 simply declared the “Reset”—and that was that as far as Georgia was concerned. Twenty percent of Georgia still remained occupied by the Russian army then, as it does to this day. And yet, all was forgiven.

Recall how in 2014 the United States refused to send Ukraine arms. This despite the 1994 Budapest agreement whereby Ukraine gave up not only the third largest nuclear arsenal in the world but also its long range bombers and missiles. Bombers and missiles that once belonged to Ukraine the Russians use today against the very country that gave them up.

We recall how after the shoot-down of MH17, the UK cabinet’s instructions were to protest, but to do nothing that would harm Russian oligarchs’ investments.

Today, we see this same attitude when German president Frank-Walter Steinmaier said that Germany owed Russia the Nordstream pipeline because of what Germany had done to Russia in WWII. But the most to suffer in fact were Poland and Ukraine, the two countries most opposed to the pipeline project.

We see it again, when, and I emphasize the timing, six months after the discovery of the horrors of Bucha in March 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron in September was still warning about the “warmongering” Central and Eastern Europeans. (Though apparently his stance has now changed.)

Most recently, we saw this attitude two months ago, when the vice president of the European Commission said that the most cogent advocate of strong security in Europe, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas of Estonia, cannot become secretary general because she comes from a country bordering Russia. This is doubly obnoxious. For one, why is that relevant? In the Cold War, NATO defended not only the border of West Germany but even West Berlin, deep in the territory of the Soviet military. But second, the longest-ever serving Secretary General of NATO for ten years already, Jens Stoltenberg, hails from Norway—a country that has had a 195-kilometer border with Russia since the founding of NATO in 1949. You’d think a senior official would know that geography. He probably does. He just doesn’t want one of those “Eastern Europeans” in the position.

Clearly we have a stitch up on the secretary general position. It can’t be an Eastern European. Instead the “Quad,”—the United States, the UK, France, and Germany—have agreed it must be Mark Rutte, who in his thirteen years as prime minister of the Netherlands has not even been able to raise his country’s defense expenditure to the 2 percent minimum agreed to by NATO. I’d like to see how he will be able cajole the other western members to raise their defense spending. We easterners did it long ago.

There are a myriad more examples of this kind of behavior and treatment of the Zwischenländer—the countries up against Charybdis in the east, the ones most at risk—being treated with disdain and as lesser countries by Scylla to our west.

Four-hundred and forty-eight million people live in the European Union. Of those, one hundred million live in the so-called “new members” that joined twenty years ago. That’s more than 20 percent of the EU’s population. Yet in the four European Commissions and European Parliaments that have served since then—and of the four most important positions in the EU—Commission president, EU Council president, the High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy, and the president of the European Parliament—only one and a half positions have been filled by anyone from the Zwischenländer: Donald Tusk was Council president for one five-year term, and Jerzy Buzek served for a half term as president of the European Parliament. One and a half positions out of a possible sixteen. I repeat, one hundred million Europeans live in those countries.

Brzezinski in a sense was an embodiment of Central and Eastern Europe—a refugee from totalitarian rule who knew more about Russia than most others, and who was denigrated for it because he was a victim. But on top of that, he was right. He was one of the most consequential thinkers of foreign and security policy in the West in the past fifty years. My question then for all of you: Do you think, given the foregoing catalogue of West European behavior toward its neighbors, that he would have been able to play any role if he had been working from Europe?

Think about it. And then think of what we need to do.

Toomas Hendrik Ilves is former president of Estonia and a guest professor at Tartu University, the national university of Estonia.

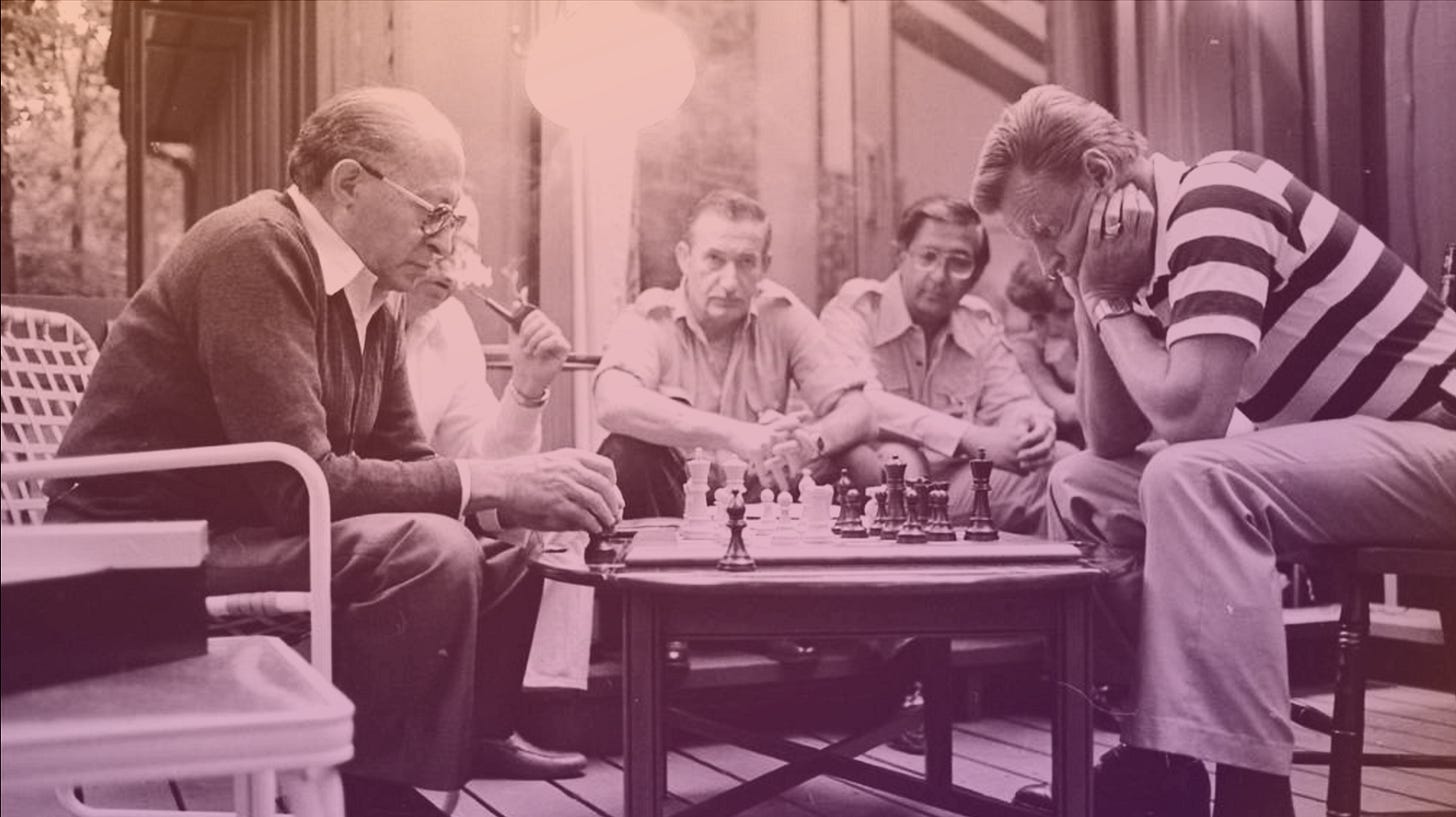

Image: Menachem Begin (L) and Zbigniew Brzezinski (R) play chess during the Camp David Summit in 1978. (adapted from a U.S. National Archives image)