Yes, You Do Have to Tolerate the Intolerant

It has become fashionable to invoke Karl Popper’s “paradox of tolerance” to justify restrictions on free speech. That’s just plain wrong.

Free speech is under attack.

In the United States, government officials are increasingly telling social media companies which forms of damaging “misinformation” they should censor, and now have the Supreme Court’s implicit blessing to do so. In Europe, overly broad restrictions on hate speech have been used to threaten people making unpopular statements with jail time. According to a government-sponsored draft bill in Canada, political opinions that could be construed as supporting genocide would be punished with life imprisonment.

Plenty of arguments against free speech lack any credible pretense of sophistication. They simply jump from the undoubted fact that many people say dumb or disgusting things on the internet to the understandable, if wrong-headed, wish that anybody who says such things should be made to shut up. But those who argue for restrictions on free speech with an ounce of sophistication have increasingly begun to invoke an idea by a philosopher whose work they otherwise studiously ignore: Karl Popper and his “paradox of tolerance.”

Invocations of Popper’s Paradox of Tolerance started to gain currency in the early 2010s, when some progressives felt disappointed with what they perceived as the ineffectual high-mindedness of Barack Obama’s administration. As Sally Kohn argued in the Washington Post at the time, liberals are wrong to see tolerance as a virtue: “Tolerance plays by the rules, while intolerance fights dirty. The result is round after round of knockouts against liberals who think they’re high and mighty for being open-minded but who, politically and ideologically, are simply suckers.” Kohn adapted a quote she drew from Popper—that “unlimited tolerance leads to the disappearance of tolerance”—to lend her desire for Democrats to take the low road a halo of authority: “To put the current political climate in Popper’s terms,” she wrote, “liberals are neutered by their own tolerance.”

Invocations of Popper became even more common after Donald Trump took office half a decade later, especially in the wake of the infamous Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Commentators now turned to the Paradox of Tolerance to suggest that it was legitimate to ban the rallies of those who hold extreme political views. An article in Quartz, published in the wake of the deadly protests, is the genre’s gold standard: “White supremacists are really, really hoping that you don’t keep reading this article. They don’t want you to learn about the Paradox of Tolerance, because then they’d lose a powerful weapon in their fight to make society more racist.” After providing a characteristically simplistic account of Popper’s thought, the article closed with the most forthright articulation of the underlying motivation: “Your heart knows when unlimited tolerance is the wrong answer. Listen to your heart. And then memorize the Paradox of Tolerance, so your head and your heart can act in concert.”

This rationalization for censorship has since entered the political bloodstream, and even gone global. Over the course of the last years, German writers have invoked it to advocate for outlawing the Alternative for Germany, a populist party that is polling at nearly 20 percent of the vote. French public radio invoked it to argue that far-right protests should be banned. A Brazilian magazine invoked it to argue that people who deny the Holocaust should suffer criminal penalties.

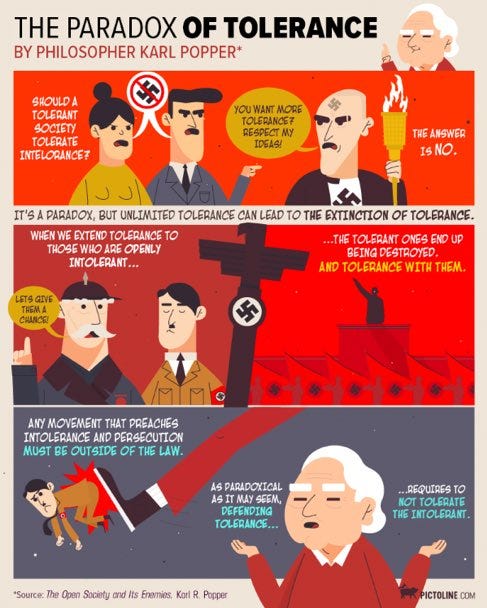

But it was a simple cartoon which really brought a suitably dumbed down version of Popper’s Paradox of Tolerance to mainstream attention. Mixing genuine quotes from Popper with misleading paraphrases, the cartoon suggests that, in a society that tolerates the expression of intolerant views, the “tolerant ones end up being destroyed, and tolerance with them.” That is why any movement that “preaches intolerance and persecution must be against the law.” For, as Popper said, “defending tolerance requires [us] to not tolerate the intolerant.”

In its original version, the cartoon’s villains are literal Nazis. But arguments against free speech are always liable to be hijacked by political movements that have identified villains of their own. And so other writers and intellectuals soon started to invoke Popper’s logic to justify tight limits on speech that happened to displease their own sensibilities. Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Philip Johnston argued that “fundamentalist Islam cannot be reasoned with because it considers itself to be an absolute truth,” making Popper’s justification of censorship especially pertinent. British academic Matt Goodwin has invoked the same logic in reference to Muslim immigrants from Pakistan: “the era of Britain being tolerant of people who are not tolerant of us needs to end.” Indeed, while the original cartoon popularized the idea that liberal societies should be intolerant towards Nazis, a later modification used the same logic to argue that we should not allow any member of Western societies to preach intolerant forms of Islam.

People of vastly differing political persuasions, fighting for vastly different political purposes, now press into their service the work of a philosopher whose books they have likely never read. But for all of their differences, they have two things in common: First, they distort the nature of Popper’s thought. And second, they have created a deep and dangerous confusion about what freedoms liberal democracies should grant their members—including those whose views may rightly be perceived as less than tolerant.

Popper did not advocate for censorship

(If you are more interested in the substantive case against censorship than in what Popper actually said, feel free to skip this section.)

Karl Popper introduced the Paradox of Tolerance in footnote 4 to Chapter 7 of his 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, and then barely returned to the topic for the rest of his life. Here is the sum total of what he had to say:

Less well known is the paradox of tolerance: Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.—In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.

This footnote is, frankly, less clear than it could be. The quotes recycled by those who invoke Popper for the purposes of censorship are contained within this passage. But so are many qualifications and reservations that go in the opposite direction—qualifications and reservations such as Popper’s insistence that we should not in general “suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies,” which his supposed devotees sweep under the carpet. So does Popper really believe that the Paradox of Tolerance requires us to shut down the speech of anyone who preaches intolerance?

To understand what Popper was saying, we need to understand who he was and what he was trying to accomplish. Popper was born to an upper-middle-class Jewish family in Vienna in 1902. As a teenager, he embraced revolutionary socialism, and was apprenticed as a furniture maker. But he gradually grew disenchanted with the orthodox Marxism of his peers, belatedly graduated from high school, and devoted himself to studying the philosophy of science. Blessed with political foresight that many of his contemporaries tragically lacked, he desperately sought to leave Austria after Hitler took power in neighboring Germany, and finally secured a job at a university in New Zealand in 1937. After the war, he moved to the recently founded London School of Economics, where he spent the rest of his distinguished career.

Popper’s most famous philosophical contribution was about how to think about science. Even today, many people think of science as a fixed set of methods for proving the truth of particular claims. When people on social media insist that we “believe the science,” for example, they tacitly assume that there are settled findings that scientifically minded people would never doubt. But Popper argued that the core of the scientific approach is not some set of methods which gives us certainty about the world, but rather a mindset which scrutinizes each and every assumption. To him, science is a process of proposing conjectures and trying to disprove them. What makes something a scientific theory is its falsifiability—the fact that it can be disproven by empirical evidence. And the reason why we should lend provisional credence to our current store of scientific beliefs is that, despite trying, we have not yet succeeded in falsifying them.

The emphasis on skepticism and free inquiry that stood at the core of Popper’s views on science also shaped his political thought. He was deeply concerned about the fact that, even after World War II, many of his contemporaries continued to believe that there was something anachronistic about liberalism. These thinkers argued that liberal democracies would likely be outcompeted by other political systems, including both fascism and communism, that gave vastly more power to its rulers. Only an embrace of totalitarian methods—whether in the form of propaganda and censorship or of state control over the means of production—could, they argued, keep its competitors at bay. But these thinkers, Popper warned in the introduction to The Open Society and Its Enemies, are wrong to “argue that democracy, in order to fight totalitarianism, is forced to copy its methods, and thus to become totalitarian itself.”

According to Popper, the fashionable “historicists” of his day, who drew from their reading of the supposed laws of history predictions about the imminent doom of democracy, overlooked the strength of liberal institutions: “Only democracy allows an institutional framework that permits reform without violence, and so the use of reason in political matters,” he argued in Open Society. To keep totalitarian systems like fascism or communism at bay, we need to sustain institutions that allow for open inquiry and grant all citizens extensive rights against their governments.

Fears about placing too much power in the hands of a society’s rulers were also front of mind for Popper throughout the chapter of Open Society in which he went on to discuss the Paradox of Tolerance. Ever since Plato, he lamented, political philosophers have focused on the question of who should rule. Once the question is posed in that way, it is inevitable that people will give such answers as “the wise,” the “faithful,” or “the proletariat.” But in Popper’s mind, even the best ruler is likely to do terrible things if his power goes unchecked. The better question, he suggested, was: “How can we so organize political institutions that bad or incompetent rulers can be prevented from doing too much damage?” Throughout his work, Popper made clear that his answer to that question included strict limits on the power of the state and a special emphasis on what he called “intellectual freedom.”1

This provides the indispensable context for parsing Popper’s famous footnote about the Paradox of Tolerance. To start off with, Popper makes clear that suppressing “the onslaught of the intolerant” should be a last resort; “as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise.” He goes on to worry about what to do about a “movement preaching intolerance”; but far from assuming that any such movement should be beyond the pale, he implies that it would only be permissible to repress those who teach their followers “to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols.” Similarly, Popper’s criterion for when to put political speech under criminal penalty seems to entail some elements of violence, or at least the threat thereof. It is when preachers of hate are engaging in “incitement to intolerance and persecution” that they can be curtailed—a much more narrow exception than those invoking Popper usually assume.2

Popper’s footnote on tolerance has been pressed into the service of a worldview which insists on giving governments the power to decide what kind of speech should qualify as intolerant, and how those accused of such wrong-think should be punished. But the entire thrust of Popper’s work suggests that he would have rejected that worldview. Far from believing that democracies are doomed to fail unless they embrace the methods of authoritarianism, he believed that it is the liberal commitment to free inquiry and to limits on the power of the state that helps them survive.

We need to tolerate offensive views—but not violent actions

The authority invoked by those who love to cite the Paradox of Tolerance to justify censorship is, as I have shown, fraudulently acquired. But this does not settle the underlying question about how liberal societies should treat the intolerant.

Are tolerant societies really doomed to be destroyed by the intolerant? And, if so, under what circumstances should liberal societies feel entitled to shut—or lock—them up? The first step in answering this question is to make explicit a distinction lurking underneath the surface of Popper’s footnote.

The word “intolerant” can mean very different things. When we talk about somebody being intolerant, we might be thinking of somebody who is unwilling to abide by the current rules of society. Perhaps they are so enraged at what they consider the immorality of the existing order that they are willing to oppose it by violent means, such as terror attacks or bloody coups. Or perhaps they hate members of some minority groups so much that they are willing to persecute them in ways that are flagrantly illegal, such as beating them up in the street or burning down their community centers. Call these people the violently intolerant.

It is obvious that no tolerant society could for long put up with that kind of intolerance. If a democratic society is unwilling to enforce its own laws against the violently intolerant, these laws quickly become meaningless.

But the word “intolerant” can—and in contemporary political debates often does—mean something rather more limited. When we talk about somebody being intolerant, we often mean that they hold some negative view about other groups. They may be sexist or homophobic or racist; they may even say offensive things about members of those groups on the internet or refuse to invite them into their homes. But they do not propose to use violence to overthrow a social order which grants members of those groups equal status, nor do they physically threaten or attack them. Call these people the non-violently intolerant.

In a free society, each of us has the right to criticize and to condemn the non-violently intolerant. We can make use of our own freedom of association to exclude them from our homes and our social clubs. We can even make laws that stop them from discriminating against the groups they dislike in, for example, commercial life. But the thing that we cannot do without giving up on a core part of our own values is to censor them or put them in jail for their beliefs.

The cartoon version of Popper’s paradox insists that the tolerant will end up being destroyed if they tolerate in their midst compatriots who “preach intolerance.” But the history of the United States, and scores of other democracies around the world, is testament to the fact that this simply isn’t true. In every age, some people have publicly preached deeply intolerant views. In every age, others have been so worried about these public manifestations of hatred that they advocated censorship. And yet, views about minority groups in a wide range of democracies that allow reasonably free-wheeling discussions on all kinds of social and cultural issues have in fact become less prejudiced over time.

Across Western Europe, South America and much of East Asia, views about sexual and ethnic minorities are vastly more positive now than they were a few decades ago. Nowhere is this more evident than in the United States, a country in which the limits on free speech are (thankfully) particularly narrow. Fifty years ago, a large majority of Americans believed that both gay sex and interracial marriage are deeply immoral. Today, a large majority of Americans support same-sex marriage and believe interracial marriage is completely unobjectionable.

The cartoonish version of the Paradox of Tolerance, in other words, is based on a conceptual confusion built atop an empirical falsehood. It’s a conceptual confusion because it refuses to acknowledge the fundamental distinction between offensive words and violent actions. And it’s an empirical falsehood because it wrongly assumes that intolerant views will, unless they are censored and those espousing them punished, win out in the market of ideas.3

A more self-confident liberalism

The idea that there is something paradoxical about tolerating intolerant views is a product of anxiety and self-doubt. It is understandable that this anxiety and self-doubt has grown in our politically turbulent times—as evinced by the headlines about the upcoming American elections or the recent riots in the United Kingdom. But the historical record suggests that liberal democracies have reason to be a lot more sanguine about the appeal of their values. When they allow genuinely open debate about sensitive issues, plenty of people will say plenty of offensive things; but the arguments that carry the day have, so far, proven to be the tolerant ones—not all the time, but much more so than under any alternative form of government.

Conversely, when societies start to censor and exclude, they nearly always do so in the name of truth or toleration or enlightenment. But the people who get to make decisions about who should be censored or excluded are, virtually by definition, the powerful rather than the marginalized. And as Popper recognized, the powerful have since the origins of recorded history been very adept at convincing themselves that they are defending freedom even as they tighten the screws of tyranny. His abiding obsession was to warn his readers about the “propagandists who, often in good faith, developed the technique of appeal to moral, humanitarian sentiments for anti-humanitarian, immoral purposes.”

Eighty years later, his argument for an open society which refuses to let the powerful decide what ideas we can publicly question remains as urgent as ever.

I am surprised that there are no comments on this essay. Despite my familiarity with Popper, I was unaware of the abuse of his ideas in service of censorship. Once again, I have learned something important from Yascha. I envy his students.

I can think of no subject more important today than the rise of the censorious instinct. It knows no political party and respects no borders. Most notably, government censorship in the land of Orwell and Mills is a danger to everyone who lives in a liberal democracy. The fact that so many in the press have made common cause with the authoritarians magnifies that danger.

Once again I find myself returning to my hero Orwell and The Prevention of Literature. For those who are unfamiliar with it, or who have forgotten it, Orwell describes a meeting of the P.E.N Club.

« Out of this concourse of several hundred people, perhaps half of whom were directly connected with the writing trade, there was not a single one who could point out that freedom of the press, if it means anything at all, means the freedom to criticize and oppose. »

Ironically, in our age that is drowning in irony, England gave the gift of liberty to Hong Kong, a gift that the dictator Xi stole. Now, British authorities seek to rob its citizens of that same gift, which in England is no less than their birthright.

« Everything in our age conspires to turn the writer, and every other kind of artist as well, into a minor official, working on themes handed down from above and never telling what seems to him the whole of the truth. But in struggling against this fate he gets no help from his own side; that is, there is no large body of opinion which will assure him that he is right. In the past, at any rate throughout the Protestant centuries, the idea of rebellion and the idea of intellectual integrity were mixed up. A heretic—political, moral, religious, or aesthetic—- was one refused to outrage his own conscience. »

Prior to its loss of liberty, the bottom 10% of Hong Kong citizens were economically better off than the top 10% of Cubans. I attribute this to the flourishing of a free people. Now, the Island nation of Great Britain seems intent on joining these unhappy islanders. Will they scour the libraries and burn Mills and Orwell as a danger? Will citizens need to hide their books as in Fahrenheit 451? That is the direction they are headed. In this, they are only at the vanguard of anglophone democracies.

Our consciences are outraged by this. They must be. Like Orwell, we should look to a Revivalist hymn for inspiration.

« Dare to be a Daniel

Dare to stand alone

Dare to have a purpose firm

Dare to make it known »

That so few have commented on this thoughtful and erudite essay reminds me of Orwell, that forgotten P.E.N. meeting, and the need for those who « dare to stand alone. »