AI Will Create Work, Not Decimate It

History shows that technological revolutions draw out human potential.

Given the nature of my work, I’m in coalitions—and a lot of conversations—focused on fortifying American democracy. And like everyone, the promises and threats associated with the rapid advancement of AI technology are top of mind for me.

When it comes to scientific discovery, optimism abounds. The promise that AI tools like AlphaFold will accelerate biomedical discovery—from new antibiotics to deeper insights into the proteins driving Alzheimer’s and cancer—sparks excitement. But there’s also a pessimism that lingers in these conversations, especially when it comes to what the future holds for workers who are not at the frontiers of science. If you write code or oversee routine managerial processes, the thinking goes, your days of productive employment are numbered. And a jobless citizenry does not bode well for democracy.

Nobel Laureate Daron Acemoğlu warns that much of today’s AI innovation is too focused on automation for its own sake, a technological path that dampens labor demand, suppresses wages, and channels the gains of innovation upward rather than outward. That path could undermine the economic foundations on which liberal democracy historically rests: broad-based prosperity, widespread opportunity for productive contribution, and a sense among citizens that they have a stake in democracy’s future.

A healthy democracy, my friends correctly observe, requires not only rights and representation, but the civic capacities that come from meaningful participation in economic life. If AI drains that sense of contribution by automating away broad swaths of work, the polity loses its civic umph: the strength and independence a self-governing people needs to hold democratic institutions accountable. Another Nobel Laureate, Geoffrey Hinton, observes that an economically irrelevant citizenry becomes increasingly invisible to democratic institutions, accelerating government capture by politically-favored tech giants.

The vibe in these conversations, in other words, is not technophobic reaction. It’s a more nuanced concern that concentrated technological power and widespread economic displacement comprise a mutually reinforcing threat to democracy.

These concerns have led many pro-democracy voices to call for sweeping regulatory and policy fixes, like taxing and restricting the development of labor-saving AI, or, alternatively, allowing AI to develop, but redirecting profits to a sovereign wealth fund to support permanently displaced workers in the jobless economy of the future.

In these conversations, the fear beneath the fear is that human potential has hit its outer bounds, and that from here on out, technology will always surpass human effort in both quality and cost. From that vantage point, sweeping, top-down remedies seem like the obvious course.

To my economist’s ear, some aspects of this narrative ring true. Basic economic theory predicts that, for a given level of quality, producers will replace high-cost inputs and processes, including those that involve human effort, with lower-cost alternatives. Such substitution effects are part of the entrepreneurial function.

But the other part of the entrepreneurial function is to search for complementarities: new configurations of resources, human and otherwise, that generate new streams of value. It’s this part of the story that, more often than not, goes missing in democracy-focused conversations about AI.

That missing piece is critical if we are to understand not only the processes that will shape our economic future, but our lives as democratic citizens.

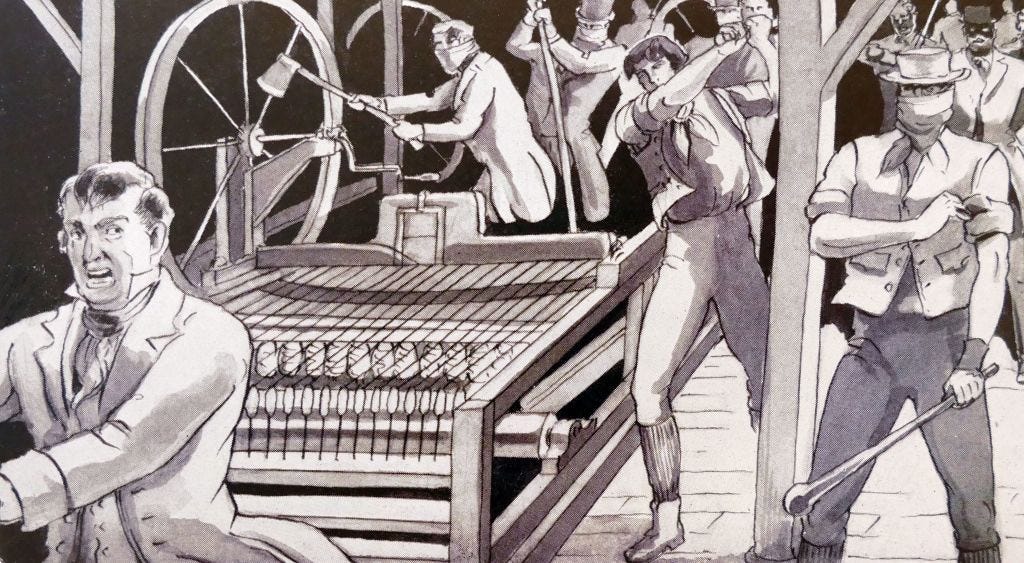

Throughout the history of the modern world, every new wave of material progress has been a story of complements far more than a story of substitutes. James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine, for example, began as a substitution story. His design replaced the less efficient Newcomen engine used to pump water from coal mines. It also displaced entire mining crews who tended older engines and made up for their inefficiencies. But the moment Watt’s steady, high-torque design proved reliable, it set off a cascade of discoveries in how physical and human capital could be recombined. Mines dug deeper, textile mills moved off riverbanks, ironworks scaled in ways no waterwheel could support, and, soon after, steamships and then railroads reconfigured the patterns of economic life. What began as a cost-saving substitution rapidly became a platform for entirely new kinds of human contribution: new skills, new industries, new forms of organization.

And it wasn’t just the industrial landscape that changed. Steam-powered textile mills offered many women their first opportunity for waged employment, growing bank accounts, and a measure of independence that coverture—the legal doctrine that subsumed a woman’s legal rights and property under her husband—had long denied. As economist Jayme Lemke observes, those gains rippled outward. Western territories eager to attract workers and investment expanded married women’s property and contract rights. Steam-powered railroads provided the affordable means to seize those opportunities, setting in motion reforms that ultimately broadened women’s democratic standing.

But complementarities emerge only through a decentralized process of experimentation, as countless individuals and firms test new ways of combining tools, skills, and ideas. These new configurations can’t be anticipated in advance because their development is not primarily an engineering problem—it’s a discovery problem. It takes the market process itself to reveal which new configurations will thrive.

Just as importantly, we rarely see the future beneficiaries of those new arrangements at the moment when the disruptive effects of substitution are most visible. The first power looms did not announce that young women would soon earn wages of their own and springboard a process of emancipatory change. As with new patterns of economic life, new patterns of democratic life had to be discovered.

When I raise historical examples of how material and social progress has unfolded, many colleagues in the pro-democracy community respond, drawing on thinkers like Geoffrey Hinton and UC Berkeley’s Stuart Russell, that today’s frontier AI represents a genuinely new category of technological change. Earlier waves of innovation, from the steam engine to electrification to the rise of computing, automated narrow domains of human effort but always left some sphere of distinctly human advantage intact. Steam and electricity displaced muscle power; computers handled rote cognitive tasks; but humans still retained a clear upper hand in higher-order reasoning, judgment, and creative problem-solving.

By contrast, they argue, artificial general intelligence appears poised to outperform humans across the full cognitive spectrum, including in domains previously assumed to be uniquely ours. If machines surpass us not only physically but intellectually, it’s unclear what special arena of relevance or productive contribution remains for people. And because these capabilities appear to be advancing at unprecedented speed, the worry is not merely sector-specific disruption, but the possibility of labor displacement on a society-wide scale, arriving all at once rather than over generations.

But this narrative misses a crucial piece of the plot. Even in a world where every task we can name has been taken on by more capable machines, human beings will want and imagine a still better set of circumstances. This is not a moral failing. It’s a feature of the human condition. At every stage of human development, even when we’ve achieved previously-unimaginable material abundance, the first thing we do is identify (in ourselves and others) further unmet needs—some base and petty, others higher order—that we just simply didn’t see before, because fulfilling them was beyond the horizon of possibility.

And here again, complementarity reenters the story. The moment that we recognize that something could be better, a sort of restlessness sets in, and the mind seeks out new combinations of tools, capabilities, and know-how that might make it so.

Yes, agentic AI may eventually perform many tasks we once considered uniquely human. But it cannot extinguish the human impulse to perceive what is missing and the mental work that spontaneously imagines how things might be otherwise. That impulse is what keeps humans perpetually intertwined with the value-creation loop. And it is how humans remain active contributors to progress, a mode of agency that underwrites not only economic renewal but the independence and initiative that democratic life requires.

And if all this still feels abstract, consider two ways the complementarity dynamic is already unfolding around us. First, look at the care economy. The United States faces critical shortages in childcare, eldercare, hospice work, and disability services—sectors where the work is rooted not in narrow tasks, but in empathy, trust, and the relational texture of daily life. Early evidence suggests that AI tools are reducing administrative burdens, improving scheduling, aiding communication, and helping caregivers tailor support to individual needs. As those tools lower costs and expand effective capacity, demand for human-centered care grows rather than shrinks.

Second, if you are one of the 63 percent of American adults who uses AI regularly, look at your own experience. Since these tools entered daily life, how many new needs have you noticed, little frictions you want smoothed, small creative ideas you want executed, gaps in your workflow you now see clearly? And how many times have you reached for an AI system, not to replace what you were doing, but to get started faster, to explore an idea, to shape something half-formed in your mind? You did not need to be a tech entrepreneur to do this. The moment a new tool appears, the human mind begins searching for ways to recombine it with what it already knows. That instinct that has us restlessly, creatively, and stubbornly pursuing new ways to satisfy unmet need is the starting point of every new complementarity.

If we treat the future as a closed system with no room for human agency to discover new needs and new configurations of resources to meet them, we will construct policy remedies that make it so, dampening the human impulse that drives discovery. In the name of protecting democracy, we could undermine the generative capacities on which democratic vitality depends.

The question before us is therefore not simply how to manage the risks of AI, but how to preserve and expand the domain in which human beings can act, imagine, and recombine the tools at hand. A society that sees only substitution will prepare for humanity’s retreat; a society that recognizes complementarity will bet on humanity’s potential. The danger is not that AI will make humans irrelevant. The danger is that we might build a political and economic order that expects us to be.

Emily Chamlee-Wright is the president and CEO of the Institute for Humane Studies.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

"History shows that technological revolutions draw out human potential.”

Well, let’s take a look at the major technological revolutions in human history

1. Tool making. Yes, it gave us enormous advantages right from the start. It also gave us the idea that we could manipulate the world to our design. And how has that turned out? We are approaching the point at which our very existence is in question,.

2. The Agricultural Revolution. Yes, it enabled us to feed far more people at the same time that it freed an increasing majority of us to do other things. How has that turned out? We have flooded the world with ourselves to the extent that a substantial portion of the rest of life on earth is at risk of extinction (except of course that part of the biome that we keep in close captivity in often appalling conditions in order to feed us), and vast numbers of us re packed into cities that are breeding grounds for disease and violence.

3 Writing. Yes, it freed us from the prison of human memory, allowing us to use our accumulating knowledge. How has that turned out? We’ve built both better and better technology which does improve life, and at the same time built weapons capable of ending all life on earth.

4. Steam power – the first invention that significantly enhanced human muscle power in ways that have transformed the world. How has that turned out? We’ve turned much of our atmosphere into an ncreasingly dangerous mixture of pollutants.

5. The computer. Yes, it has given us powers of usage and creation utterly beyond any previous belief. And the internet, well, I won’t comment on the mixed bag that is.

And yes, this has been a simplification that does not do justice to anywnere near all the facts. But this we do know.

Like all the other really significant inventions, AI will turn out to be a double edged sword, because in the final analysis, our tools are as good or as bad, as advantageous or as dangerous as the men and women using them.

This essay suggests why economists need to get out more. The abstraction and generality of the analysis ("we" will do this, "human nature" will do that, etc.) completely ignores the fact that millions of careers will be destroyed and people--real people (not the abstract categories moved about on the chessboard in this piece)--will have their dignity and livelihoods destroyed. For those people, this destruction is forever. There lives will be ruined. "Well, them's the breaks, we'll catch you down the line in the next generation," doesn't somehow add up for me.