All COPs are Bastards

The UN’s annual climate change conferences refuse to get real. Here’s what a more honest conversation would look like.

Tomorrow, the annual cavalcade known as COP gets underway in Dubai, of all places. You can look forward to lots of self-important hand-wringing from everyone who is anyone in the international scene. Our progress towards Net Zero will be declared gravely insufficient, and pious declarations of intent to Do Better will pour forth. A high-minded declaration will be signed and many photos will be taken.

And then, a year later, we will do it all again.

You’ll hear plenty about stock-taking in the press coverage from Dubai. I can save you some time. Global CO2 emissions rose again last year, as they do every year, barring a pandemic. They’ve grown from 35.6 billion tons in 2015 to 36.8 billion in 2022, with a new record expected this year that could well exceed 37 billion tons. Looked at globally, the energy transition we keep hearing about has yet to begin.

Up a creek, without a Kaya

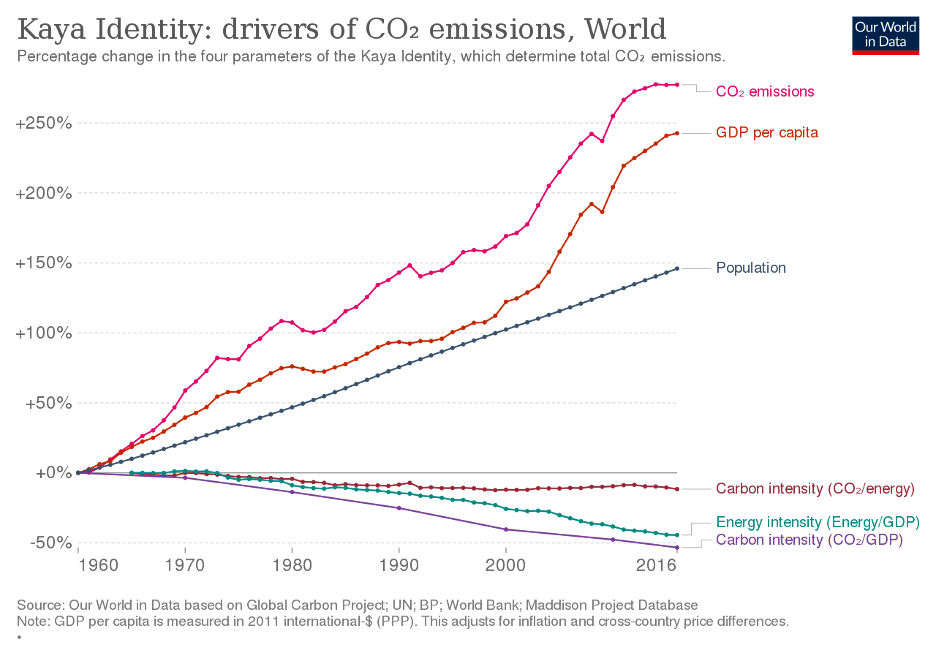

Ask actual climate scientists why we continue to pump more and more carbon into the atmosphere, and very soon you’re going to be talking about the Kaya Identity. What is the Kaya Identity? It’s the accounting framework the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the climate science community relies on to structure our thinking about the drivers of emissions.

First proposed by Japanese energy economist Yoichi Kaya back in 1993, the Kaya Identity expresses global CO2 emissions as the product of a simple mathematical equation with just four variables: population, GDP, the energy-intensity of GDP, and the carbon intensity of energy. Multiply these four variables together and you get a figure representing the amount of CO2 we pump into the atmosphere. The math is disarmingly simple. And it’s an accounting identity, true axiomatically: not something you can really argue with.

Now, climate scientists spend a lot of time measuring each of the terms in the Kaya Identity as precisely as possible. And what they find, year after year, like clockwork, is that the change in the third and fourth variables is remarkably stable. The global energy mix is getting cleaner, and the economy is getting more energy efficient, but the pace of progress is slow.

In fact, one of the most sobering realizations when you really dive into this literature is how powerless humanity seems to be: even momentous legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act has minimal impact on global aggregates. Why? Because for every country working flat out to decarbonize its grid there are countries like China planning a hundred new coal-fired power plants.

But wait, if we are indeed using less and less carbon to produce a unit of energy, and less and less energy to produce a unit of wealth, how on earth is it possible that carbon emissions keep rising?

One look at this graph answers the question: population and GDP, the first two variables of the Kaya Identity.

In recent years, the global population has kept growing at around 1% per year, and GDP at around 2%. This overwhelms our modest advances on energy and carbon intensity. At the global level, the trends are relatively stable, and have been for decades. This is a fact so inconvenient that COPs simply tiptoe around it.

Delusions of Degrowth

Not everyone, of course, tiptoes around it. In climate circles in Europe, “de-growing” the economy is all the rage. Degrowthers go there, shining a light on the first two factors in the Kaya Identity, the ones that make us squirm. And they’re not exactly wrong: as a matter of plain arithmetic there’s no question that the reason carbon emissions continue to rise is that the global population keeps growing, and is also getting richer on average. The conclusion seems overwhelming: if you want to reduce atmospheric carbon, you’re going to have to tackle all four factors in the Kaya Identity, not just the politically approachable third and fourth ones.

But budging the needle on population and GDP is hard. It’s possible in theory, but doing so would require an exertion of state power that’s just not compatible with democracy or basic humanity. China’s One-Child policy showed how it could be done: through heavy-handed state coercion. Mass forced sterilization. Heavy pressure to abort second pregnancies. Infanticide. It’s entirely obvious that no democratic government could pursue anything of the sort: voters wouldn’t stand for it.

As for forcing economic degrowth, the situation’s much the same. Voters worldwide expect governments to do what they can to make them more prosperous. You could try to campaign on a platform of making people less prosperous but, y’know, good luck with that.

Many on the political right suspect the environmental left of harboring plans to pursue just such heavy-handed interventions. And those suspicions are not wrong, exactly, because the activist left gets the Kaya Identity. It wields tremendous institutional power, and so mainstream politicians really want to be seen as on side with them.

But there are limits to what these politicians will actually agree to do. This is especially obvious if they are democratic politicians whose power depends on their ability to win elections. Elections are very hard to win for parties that actively try to make most people poorer.

But it’s not just about democracies: autocrats also avoid economic stagnation and decline if they can, because they know autocratic regimes become vulnerable when majorities are jobless and disaffected. The one thing no sane politician, democratic or otherwise, will sign is their own political death sentence.

And so the good news is the bad news. Degrowth won’t be pursued as a policy because there’s no imaginable political equilibrium to support it, which means that emissions will continue to grow for the foreseeable future.

This conclusion is dispiriting. But unpleasant facts are better faced forthrightly than covered up or wished away.

The Great Dimmer Switch in the Sky

Once we accept the bitter truth that we don’t know how to reduce carbon emissions anywhere near fast enough to avert drastic atmospheric changes, we can have a more honest discussion about the options we do have. All of which are bad.

The COP-sanctioned magic solution is to pin our hopes on Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), a set of technologies that remain about two orders of magnitude too expensive to play a real role in decarbonizing the atmosphere. Even if costs come down extremely quickly, it takes some heroic assumptions to think we can suck CO2 out of the atmosphere fast enough to avert catastrophic consequences in the next two decades. As it is currently used in COP world, CDR is magical thinking: an arm-wavy way of signaling that you expect someone to think up a solution later... and that you’re willing to stake the future of the planet on it.

If CDR won’t work, what will? The least terrible (but still ghastly) solution is solar geoengineering. Scientists have known for decades that we can quickly and affordably cool the planet by mimicking processes that large volcanoes set off naturally. A relatively small fleet of high-altitude planes pumping reflective particles into the stratosphere would do the trick.

I’m personally convinced this is where we are headed. The scenario is fleshed out in The Ministry for the Future, Kim Stanley Robinson’s hair-raising 2020 novel that imagines truly cataclysmic weather events in the 2030s pushing the governments of the worst affected countries to move unilaterally, in a panic.

Mainstream environmentalists have for many years prevented a debate on geoengineering because they fear it will undermine decarbonization efforts. But every year the kind of grisly scenario in The Ministry for the Future grows more likely. And so the debate is slowly coming out into the open, with more and better theoretical research emerging from this space. Yet last year, UNESCO offered a single panel on geoengineering within the COP27 conference.

To be abundantly clear, fiddling with the stratosphere is not a get-out-of-jail free card. It would do nothing to halt ocean acidification, so its impact on biodiversity loss would be limited. Worse, the potential unforeseen impacts of any geoengineering plan are grave. Scenarios where a purposefully altered climate favors one region of the world at the expense of another suggest genuinely troubling trade-offs, and introduce potentially poisonous geopolitical risks. What if the cost of stopping the most destructive heat waves in India is borne by Chinese farmers, suddenly facing droughts? The mind boggles.

But while there are many good reasons to be scared of a geoengineered planet, there are more (and better reasons) to be scared of runaway climate change. And so the world is at a strange juncture: sleep-walking into a future it refuses to talk about, and swatting away the resulting cognitive dissonance with fairy-tales about Net Zero and feel-good bans on plastic straws.

Sooner rather than later, we’re going to be forced to engineer our planet’s climate. It will be one of the riskiest things the human race has ever attempted. Shouldn’t we do the research on it now, so that we know what to expect when we’re forced to implement it? And wouldn’t this be a more fruitful conversation to have at a meeting of world leaders on climate change than the annual festival of disingenuous preening that COP has become?

Francisco Toro is a contributing editor at Persuasion.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

While I’m sure some governments will attempt geo-engineering as the push to go green doesn’t go very far, there’s another option societies have: adapting to a planet with a much more turbulent climate. There would certainly be high costs (overhauling and reinforcing infrastructure, trying to shift populations away from coasts, trying to grow different crops, efforts to reduce consumption during economic growth periods to ensure surpluses during climate-induced economic hard times). But they may be costs societies are more willing to bear than the risk of technological tinkering with potentially disastrous results.

Your compelling analysis really lays out the problem. Your graph shows so clearly how global CO2 emissions and global wealth per capital rise over time at rates very similar to the rise in global population. I can add one more voice to the voices already supporting yours. Not mine, Pogo’s. He was the animated possum in Walt Kelly’s syndicated cartoon. He was a relentless advocate for Okefenoekee Swamp, his home. He summed up the entire problem for his world in just nine words: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”