Beyond the First Amendment

The Constitution has its limits. It’s up to us to stop the censoriousness.

“I know no country in which, speaking generally, there is less independence of mind and true freedom of discussion than in America.”

When these words appeared in the first volume of Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, the First Amendment was forty-four years old. Its adoption in 1791 marked a watershed in the protection of free speech for the citizens of democracies against their governments. Americans today consider it to be the most important constitutional amendment.

But despite the First Amendment’s radical promise—freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and petition—Tocqueville was startled to discover a culture of profound unfreedom when he visited America. He saw people afraid to speak up for their true beliefs in front of their neighbors. He saw the chilling effect of conformity as citizens toed the line on matters of politics and religion. To a foreigner like Tocqueville, Americans “will disclose truths…but when they go down into the marketplace they use quite different language.”

The reason, he speculated, is that morality in a democratic republic doesn’t come from edicts handed down by a religious or political hierarchy, as in an authoritarian state. Instead morality comes from within, from the people. Public mores are subject to the capricious and cruel whims of the crowd, and this impacts politics, culture—just about everything.

What Tocqueville described was a subtle and insidious type of coercion that the First Amendment couldn’t touch. He was right to be worried. Even though First Amendment rights were significantly expanded in the centuries that followed, if we survey the most contentious issues of 2022 it’s clear we are still dealing with a crisis of culture that goes well beyond anything the Constitution can hope to solve.

Let’s begin with the problem of free speech on university campuses. Hundreds of individuals can attest to the proliferation of pile-ons in place of reasoned disagreement, and the disproportionate reputational penalties that students and teachers are subjected to at the hands of administrative bureaucracies. Despite popular notions, this is not just a left-wing phenomenon: a database compiled by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) shows that around 35% of attempts to get professors fired come from the right.

The First Amendment is not silent on the question of free speech on campus. In March, a federal court ruled that a professor could file a lawsuit against the University of North Texas after the university potentially violated his First Amendment rights when it fired him for criticizing the concept of “microaggressions.” This decision is no aberration: the Supreme Court has long upheld the principle that professors can speak out on matters of public concern.

But this hasn’t prevented a culture of censoriousness from proliferating. For every person who is fired, and who has the option to file a First Amendment lawsuit against their employer, and who succeeds in convincing a court that their constitutional rights were violated, there are countless others who simply choose to adjust their teaching methods rather than face years of litigation. This is casting a very real pall over free speech. At a time when the number of universities enacting speech codes that flagrantly violate the First Amendment is diminishing, there is mounting evidence that academics are self-censoring.

Furthermore, the First Amendment only covers people working at public institutions, not private ones. Private universities are allowed to regulate speech. True, if a private university chooses to adopt free speech guidance and then breaks its own guidance, students can seek legal action for breach of contract, and the government may revoke any federal funding the university receives. But there is nothing to compel a private university to pledge to uphold freedom of speech in the first place.

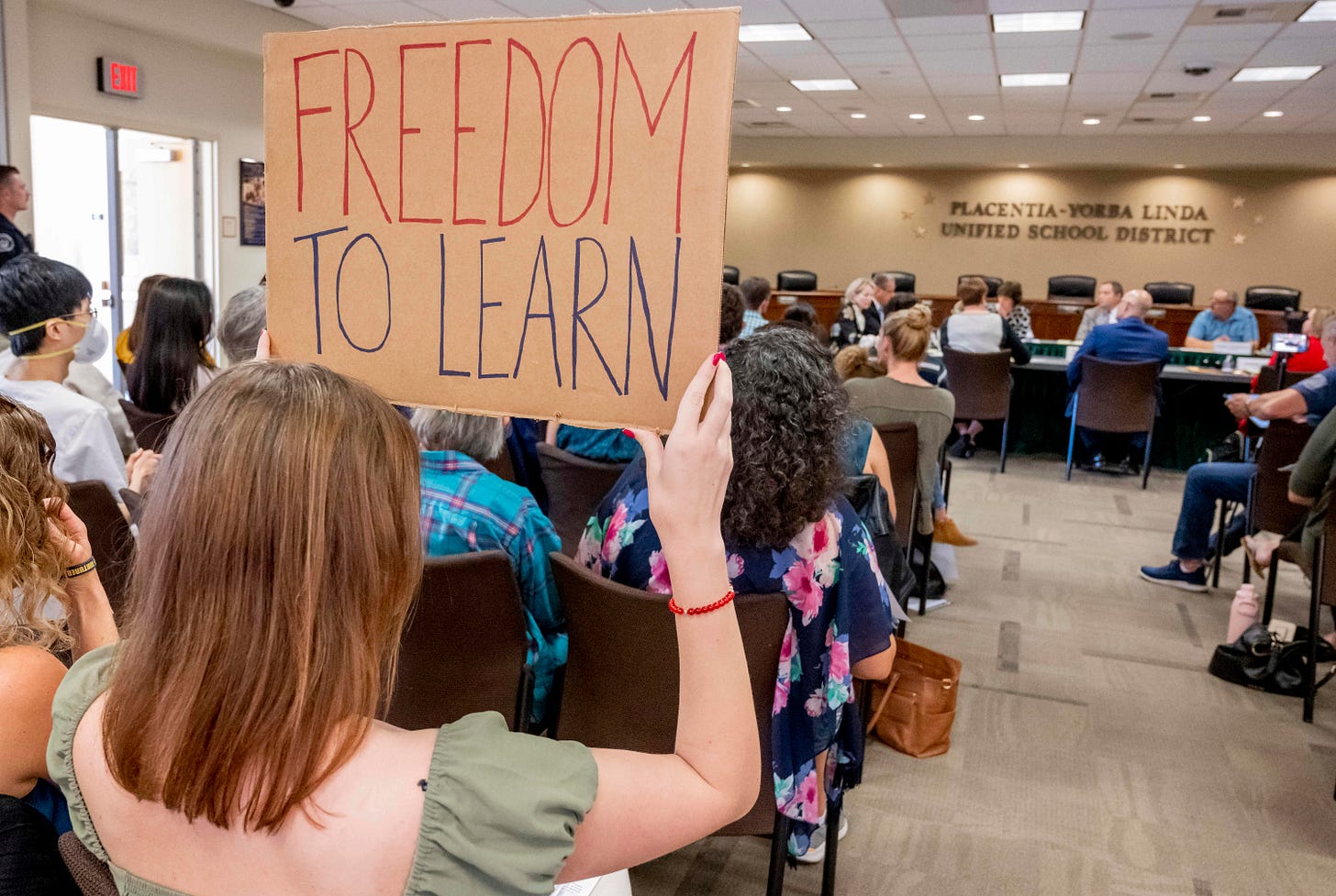

The First Amendment is similarly limited when it comes to perhaps the biggest fight taking place in education right now. Over 1500 books have been banned in 86 school districts across the country since July 2021 as part of a wider array of right-wing attempts to outlaw so-called “critical race theory.” This has had a deep impact on K-12 curriculums. In Texas (and elsewhere), educators have been confronted with vague directives that aim to prevent students from feeling “discomfort.” In New Hampshire, one teacher recounts how she started steering clear of the legacy of Jim Crow. David French has shown how even the writing of Martin Luther King Jr. falls afoul of proposals in Tennessee and Kentucky.

What’s taught in schools should obviously be up for debate. But banning hundreds of library books, threatening fines against teachers, and encouraging parents to sue under vague laws is hardly the way to have an appropriate discussion about how the history of race in America should be taught.

Some of these regulations may be struck down as violating the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court has (narrowly) reversed book bans in the past. But this is not a reliable mechanism: Will Creeley, the legal director at FIRE, told me that “there’s a real question whether the Court as currently constituted would reach a similar decision on the same facts.” And there is little hope that the courts will say anything about teaching material used in K-12 classrooms, over which states enjoy very broad control. The bottom line is that for as long as officials retain broad powers, the most important battles will take place in school boards and legislatures, beyond the purview of the First Amendment.

Finally, away from classrooms and courtrooms, the most troubling manifestations of censoriousness are those accompanied by the possibility of violence. You need only read accounts of the threats directed against anti-Trump Republicans to appreciate the grassroots radicalization that has taken place in some churches and GOP circles, and the violent coercive mindset that has been unleashed. Again, the First Amendment only has limited use in such cases. Hateful speech loses constitutional protection when it threatens to incite imminent violence—the “true threats” doctrine. But most instances simply do not meet that threshold, and pile-ons of officials and lawmakers have proliferated.

In these polarized times, many of us dream of a society in which there are no undue burdens on expressing your opinion; one in which you will not face pressure to conform in your daily life, and which allows people to access the broadest possible range of ideas and opinions. The First Amendment is vital to the functioning of American democracy—but it can only go so far toward building such a society.

None of this is the fault of the First Amendment. It’s there to protect citizens against the government, and any constitutional amendment that went further—that tried to regulate what private citizens can and can’t say to each other—would be dangerously vague and arbitrary. But censoriousness is still a problem. What, then, is the answer?

Some people advocate for more censorship. They point to social media companies (after all, most pile-ons and radicalization is mediated via the internet), who have wide discretion to moderate content as they see fit. But aside from the obvious danger of creating even more mistrust, censorship of this sort is always arbitrary. Social media companies can only hire so many moderators to trawl through the avalanche of garbage: some individuals will be targeted while others get away scot-free. And while cleaning up online discourse could help mitigate some of the dynamics of censoriousness (such as pile-ons and threats), it will hardly prevent activist groups from getting together to demand that a state passes an anti-CRT law, or that a university censures a particular professor.

A better solution is to recognize that building a culture free from censoriousness is a bottom-up endeavor. That could mean participating in nonprofits which aim to reduce polarization and facilitate dialogue between cultural tribes. It could also mean pressuring social media companies to alter their algorithms so that they don’t favor the most inflammatory content (a very different solution to top-down content moderation).

Above all, it will mean encouraging millions of individuals to set aside the rhetorical cudgels. The very same democratic arenas in which censoriousness flourishes must be injected with new energy to serve constructive, tolerant ends. This is the hardest task of all, given our current levels of polarization and mistrust. But it is a necessary task—only then can we achieve the “independence of mind and true freedom of discussion” that Tocqueville recognized is so vital to the flourishing of a republic.

Luke Hallam is an associate editor at Persuasion.

The key is BOTH SIDES setting aside their partisan cudgels, which means the Left must abandon their censoriousness and book banning as well.

For every school/school board banning books. there are probably 20 teachers preaching racial identify politics as a "fact". The pandemic had the unintended side effect of allowing parents to see what was being "taught" in schools. like it or not, CRT is the dominant religion of the left and that most assuredly includes most K-12 teachers.