Europe Learned Nothing From the Danish Cartoon Affair

Twenty years later, blasphemy laws continue to stalk free societies.

Growing up in Denmark in the early 2000s, I rarely worried about my right to free speech. In this cozy haven of liberal values and secular democracy, speaking freely felt as natural as breathing. Few contested this state of affairs, least of all religious groups, whose influence had long since faded.

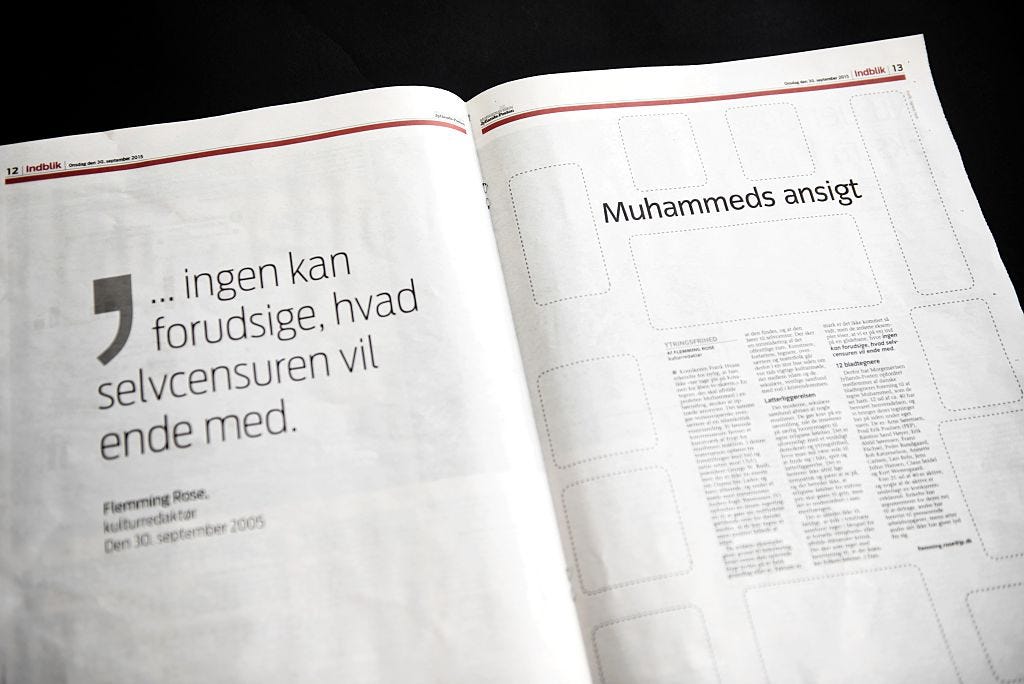

That outlook changed twenty years ago today. On September 30, 2005, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published an editorial titled “The Face of Muhammad,” accompanied by 12 cartoons, some of which depicted the Prophet Muhammad. The publication set off a global firestorm and turned criticism of Islam into a minefield that remains deadly to traverse even in open societies. And rather than defending the principle at stake, European democracies are increasingly choosing appeasement—trading away free speech for the promise of a precarious peace.

The latest example comes from London. In June, Turkish immigrant Hamit Coskun was fined £240 for a religiously aggravated public order offence after burning a Quran and shouting profanities against Islam outside the Turkish consulate. Coskun insisted his protest was aimed at Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s authoritarian Islamism. But the presiding judge ruled that Coskun was “motivated (wholly or partly) by hostility” toward Muslims, and deemed his conduct disorderly—citing, as evidence, that he was physically attacked by two bystanders. In other words, the violent reaction to his peaceful protest was the basis for the criminal charge.

The case became more troubling still last week, when the man who assaulted Coskun with a knife was spared jail, with the judge noting that the assailant felt “deeply offended” as a mitigating circumstance. The asymmetry is glaring: the protester is punished for offending sensibilities, while those who turned to violence avoid serious consequences. This is appeasement in practice—embedding a “Jihadists’ Veto” into law and precedent, and ensuring that intimidation pays.

Unlike me, Flemming Rose, the cultural editor at Jyllands-Posten who commissioned the Danish cartoons twenty years ago, did not take free speech for granted. Rose felt a disturbance in the Enlightenment principles that had long sustained Western European societies. He sensed danger signs in 2004 when an Islamic fundamentalist murdered Theo Van Gogh, the director of the Islam-critical film Submission, on the streets of Amsterdam. Later that year, a Danish lecturer was assaulted for reciting the Quran in class (extremists view it as a crime for non-Muslims to read from holy texts). In 2005 a Danish children’s author couldn’t find illustrators for a book on Muhammad. In response, Rose invited cartoonists to depict Muhammad as a way to test the boundaries of self-censorship and the commitment to free speech and tolerance.

In an editorial accompanying the cartoons, Rose wrote that affording special protections for any particular religion or its adherents was “incompatible with a secular democracy and freedom of speech, where one must be prepared to endure mockery, scorn, and ridicule” regardless of group identity. Far from an act of “Islamophobia” or anti-Muslim bigotry, Rose’s editorial was about taking freedom and equality seriously, even when it is uncomfortable to do so. And in Denmark, the initial response was relatively restrained. Some criticized the cartoons as needlessly provocative; others defended the right to publish them.

Internationally, however, regimes in Egypt, Iran, and Pakistan amplified the controversy, stoking outrage to claim the mantle of defending the global Muslim community. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), representing 57 Muslim-majority countries, launched a campaign to reframe the cartoons not as religious satire, but as a form of hate speech. Leveraging existing provisions in international law—particularly Article 20 of the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights—the OIC pushed for global laws criminalizing “defamation of religion.”

Western governments and human rights groups, unsure of how to balance respect and rights, at times gave credence to this narrative. The U.S. State Department initially condemned the cartoons as “inciting religious and ethnic hatreds.” Amnesty International released a statement suggesting the cartoons might violate international hate speech standards. The Nobel Prize-winning German writer Günter Grass went so far as to liken the cartoons to Nazi propaganda.

Though the OIC campaign ultimately failed—thanks in part to a counteroffensive by the Obama administration in 2011—the episode revealed a deeper vulnerability. Less than two decades after the Rushdie Affair, liberal democracies were no longer confident in defending their own foundational freedoms.

And if legal mechanisms proved insufficient to silence dissent, violence filled the gap. In 2015, a decade after the Danish cartoons were published, two gunmen stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, killing 12 people. In 2020, French schoolteacher Samuel Paty showed his civics students the Charlie Hebdo cartoons during a lesson on freedom of expression. He was beheaded in the street days later by a radicalized teenager.

Even Denmark, where the crisis began, has shifted course. At the outbreak of the cartoon crisis, the Danish government refused to compromise free speech. In 2017, the Danish parliament repealed the country’s centuries old blasphemy ban—a symbolic victory for free speech over religious dogma. But just six years later, that progress was undone. After a series of Quran burnings by far-right activists triggered renewed outrage and threats from the Muslim world, Danish authorities reversed their position. In 2023, a new law was passed criminalizing the “improper treatment of scriptures,” effectively reintroducing a narrower blasphemy ban. (This May, two Danish far-right protestors were the first to be convicted under the new law. Their crime: tearing out two pages of a Quran and dropping them into a puddle of water during a public debate about the same law that would later be used to convict them.)

More capitulatory acts to the “Jihadists’ Veto” would follow. The OIC revived its campaign to ban criticism of Islam and achieved a symbolic victory in 2023 when the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution condemning desecration of holy texts as incitement to hatred.

Also in 2023, two Iraqi refugees living in Sweden burned a Quran in protest against Islamist extremism. They had secured police protection for the demonstration, explicitly stating in advance that a Quran would be burned. While certainly inflammatory, the act was understood to fall under Sweden’s broad protections for free expression—protections rooted in the abolition of its blasphemy law in 1970. But fearing diplomatic consequences and religious violence, Swedish authorities charged them with incitement to hatred, even though their protest was directed at Islamist extremism.

In January this year, one of the refugees, Salwan Momika was assassinated in his apartment just days before his court date. In a model democracy, peaceful speech was condemned twice: once by the legal system, and once by the very religious fundamentalists the law was meant to appease.

Europe’s legal regression is based on the assumption that in diverse societies free speech must be curtailed to avoid offense and preserve social harmony. But no amount of sugar coating with appeals to “tolerance” and “respect” can hide the bitter truth that fear of intimidation and violence are the real driving factors.

In this new climate, violence is not merely a threat—it has become a strategic tool to reverse the hard-won freedoms that once unshackled the human mind from state-imposed religious diktats. The lesson is stark. When democratic governments criminalize peaceful expression, they do the work of extremists for them—and still fail to stop the violence.

Free speech, once lost, is not easily regained. Twenty years on from Flemming Rose’s social experiment, the question is no longer whether free speech is under threat. It’s whether liberal democracies still have the will to defend it against forces determined to destroy it.

Jacob Mchangama is the Executive Director of The Future of Free Speech and a research professor at Vanderbilt University. He is also a Senior Fellow at The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and the author of Free Speech: A History From Socrates to Social Media.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I think the very concept of “hate speech” is problematic. Who gets to define what is hateful? The concept that only certain groups can be victims seems to be enshrined in law. Or, offending a buffoonish politician (I am American) This was a sad story.

Great article! Thank you Persuasion for publishing this. Everyone knows that Christianity can be attacked and criticized even in extreme and hateful terms. It often is. However Islam is off limits for any criticism. Increasingly "anti-semitism" is also invoked over any criticism of Israel's wars and influence in US politics.

Another paradox is this: Hateful violence of all kinds is tolerated in thousands of films and video games freely available to everyone on the internet. But much milder comments on twitter against immigrants, or transgender activists, are claimined by EU censors to be so dangerous and hurtful that people are being arrested for these comments.