Europe’s Move Towards Post-Populism

Western populists are running out of steam, and increasingly mainstream post-populist parties are replacing them.

The expression “post-fascist” became popular in September 2022 on the eve of Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) winning Italy’s legislative elections. Was the epithet unfair? True, Meloni’s party has a historic connection with Italy’s postwar post-fascist movement. FdI descends from the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a party created in the 1950s by former fascist mid-ranking officials with the intention of offering some continuity with Mussolini’s regime (under the ambiguous slogan “Do not deny, do not restore”). But much has happened in seventy-five years. Today, FdI stands increasingly as a mainstream European conservative party.

The prefix “post” still applies to Meloni’s party, though—not as “post-fascist,” but as “post-populist.” Fratelli d’Italia is akin to a number of parties in Europe that are shifting their political positioning in an attempt to re-appropriate the left-right divide. Some of these parties—like FdI, the Sweden Democrats, and the True Finns—are moving from the far right to the mainstream right; others, like New Democracy in Greece and Spain’s People’s Party, are moving rightward from the center. The aim of this repositioning is to supersede the cleavage between the elite and “the people,” thereby making populism less relevant.

Post-populism is very much the result of the dead-end that populists in Western countries had reached by the early 2020s. Despite a favorable, revolutionary mood in the mid-to-late 2010s—populist successes have included Brexit and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, the 2017 election of Andrej Babiš in the Czech Republic, and the 2018 coalition in Italy between the far-left Five-Star Movement and the far-right Lega—Western populists started to run out of steam by the end of the decade. They registered no major electoral victories in the year 2019, and the new decade ushered in new, disruptive events that exposed the limits of what they could achieve.

By far the most important of these events was Covid-19, which profoundly disrupted Europe’s social fabric. It might come as a surprise that the pandemic highlighted the similarities rather than differences between the old mainstream elites and the would-be populist elites, since in the end, with more or less zeal, populist and non-populist leaders in power ended up taking roughly the same measures to balance economic interests and the public’s well-being. Some of these policies, like lockdowns, were more associated with the establishment, while others, such as the closure of borders, were in line with populist demands, but in the end nearly all leaders implemented the whole of them to various degrees.

Nonetheless, perceptions of the competence of populists versus non-populists shifted during Covid. During the 2010s, people increasingly looked to populists for radical solutions to long-standing grievances. Yet the anger that had been a defining feature of that period took a back seat during the pandemic to both fear and, over time, weariness. Sciences Po’s political trust barometer captured this in the spring of 2020, when weariness supplanted every other feeling in French public opinion, jumping from 28 percent to 41 percent as the emotion that “best defined your current state of mind.”

Other events such as Brexit helped change the mood in Europe and make voters less attracted to populist adventurism. But it was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that probably put the final nail in the coffin for European populism, which in many instances had been closely associated with the figure of Vladimir Putin. Putin was the populist poster boy projecting strength, power, and control to a public yearning for these. The invasion completely changed Putin’s image and showed him for what he really is: the head of a mafia state and a gambler who, having run out of luck, doubles down at every move with the hope that his winning streak will return. Many politicians who had associated themselves with their father-figure suffered the consequences: In France, both Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen dipped in the polls after the invasion (the former never recovered), much like Italy’s Matteo Salvini, who has left the leadership of the right to Meloni.

While Meloni and others continue to revisit the disruptive themes that made the populists appealing—such as immigration, state intervention in the domestic economy, and management of trade—they mix these themes with important elements of mainstream politics like Atlanticism, Europeanism, economic liberalism at home, and respect for existing institutions and the rule of law. The result is that more and more European post-populists on the right seek to obtain change through the system, rather than destroy it.

European political figures on the Left are also moving toward post-populism. Indeed, the likes of Beppe Grillo in Italy, Pablo Iglesias in Spain, and Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom have all left the stage and been replaced by more moderate leaders, but post-populism on the left is thus far not as ideologically homogenous as it is on the right. It is hard to know whether its future lies with the Danish Left, which has given up the fight on migration in order to focus on reforming the Nordic social model, or with the southern European model, where would-be post-populists like Elly Schlein in Italy and Pedro Sánchez in Spain have driven forward many issues of the populist far left in parliaments rather than on direct democracy platforms such as social media or the street.

There are still uncertainties as to post-populism’s shape and even its future. Despite a clear retreat, populism is not dead yet, and could make a comeback should social and economic conditions in Europe worsen. Elections in Spain and Poland in the coming months will likely be crucial tests. Perhaps even more consequently, the 2024 elections in Europe, the United States, and the United Kingdom could make or break both populism and post-populism.

Thibault Muzergues is senior advisor at the International Republican Institute. He writes in his personal capacity. Twitter: @TMuzergues

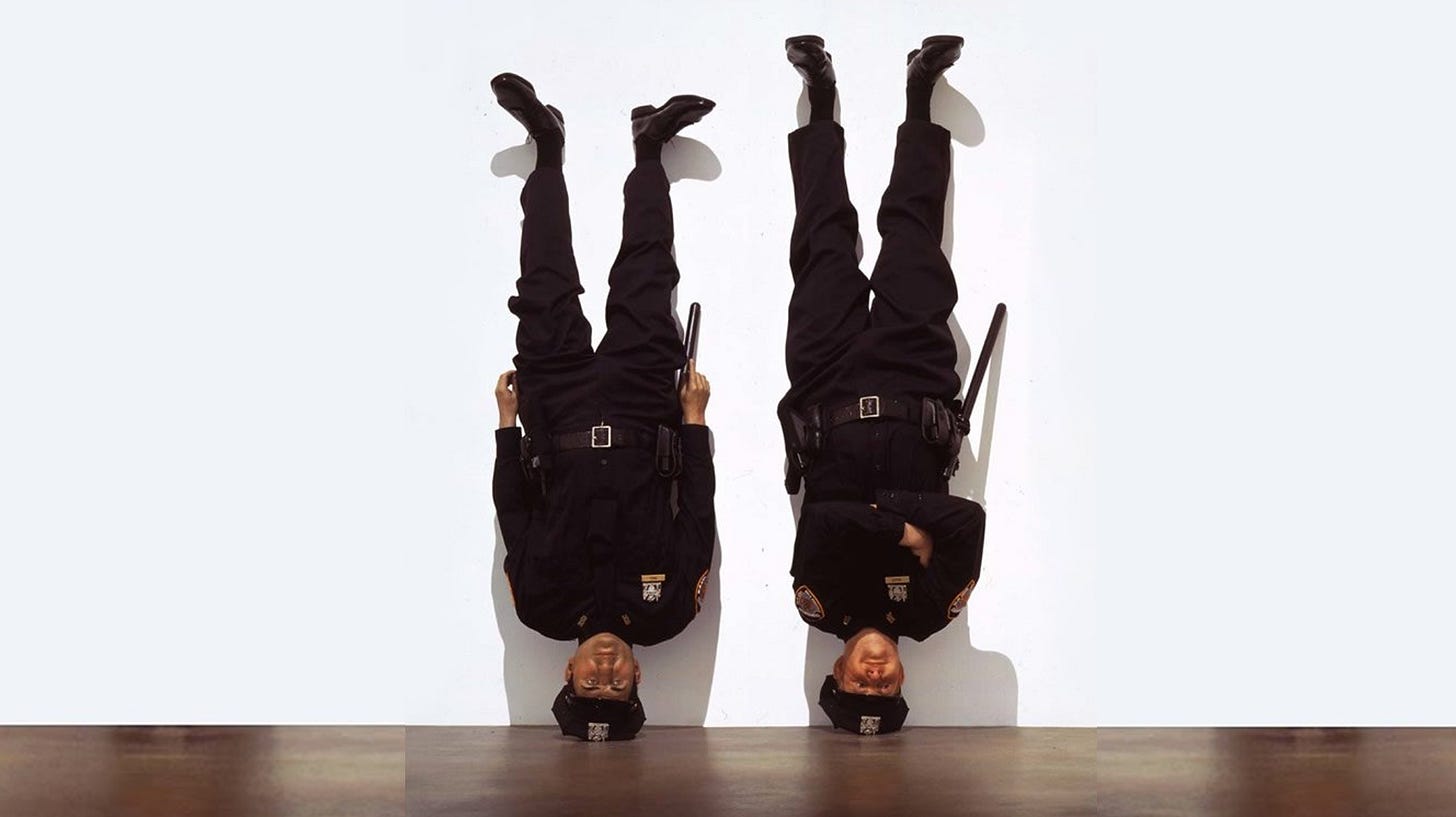

Image: "Frank and Jamie," Maurizio Cattalan, 2002. (Il Circolo dei Tignosi)