Inside the Battle to Abolish Birthright Citizenship

Even if the Supreme Court overturns Trump’s executive order, he may eventually get what he wants.

The current Supreme Court term is shaping up to be yet another historic one—this time devoted to settling which of Donald Trump’s many novel assertions of presidential power are legal.

On Friday, the news dropped that the Court will take up the legality of the president’s Inauguration Day executive order eliminating birthright citizenship—the automatic conferral of citizenship on any person born within the United States, regardless of the citizenship status of the children’s parents. That order has never gone into effect, because it immediately sparked lawsuits that resulted in lower courts issuing preliminary injunctions against its enforcement. When Solicitor General D. John Sauer made the government’s case before the Supreme Court last spring, he did not ask the justices to weigh in on the legality of the order itself but only on the propriety of lower courts issuing “universal” or “nationwide” injunctions. The resulting decision, Trump v. CASA, Inc., largely sided with the administration, ruling that such sweeping injunctions are often broader than necessary.

That has left the ultimate fate of birthright citizenship uncertain. We knew the Supreme Court would need to clarify its legality, but we didn’t know when it would do so. Now we do. The justices will hear oral arguments early next year in Barbara v. Trump, a case involving a class of babies born on or after February 20, 2025 who would be denied U.S. citizenship by Trump’s order, with a decision to follow by the end of the Court’s current term, in late June or early July of 2026.

The Battle Ahead

MAGA world obviously thinks Trump’s order should stand. Most non-MAGA lawyers and legal experts, on the other hand, consider it close to unthinkable that the Court could allow the elimination of birthright citizenship if the case is decided with even a modicum of good faith. The 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States….” This passage has been widely interpreted, for more than a century and a half, to codify the English common-law doctrine of jus soli (right of the soil) and therefore to authorize birthright citizenship. Trump’s order will be shot down, by this view, unless the Supreme Court’s conservative majority acts as a rubber stamp, endorsing the president’s authoritarian effort to overturn the clear language of the 14th Amendment.

Yet the distressing fact is that the prevailing reading of the citizenship clause isn’t quite as obvious as defenders of birthright citizenship claim. Until recently, very few scholars dissented from that consensus. But a few did, and their arguments will be available to the Supreme Court’s conservatives, if they want to draw on them. That could give them all the ammunition they need to side with the president.

But the more likely outcome may be a decision that falls short of allowing Trump’s order to go into effect while also greatly undermining the constitutional foundation of birthright citizenship, the fate of which could be left in the hands of Congress.

The Birthright Citizenship Consensus

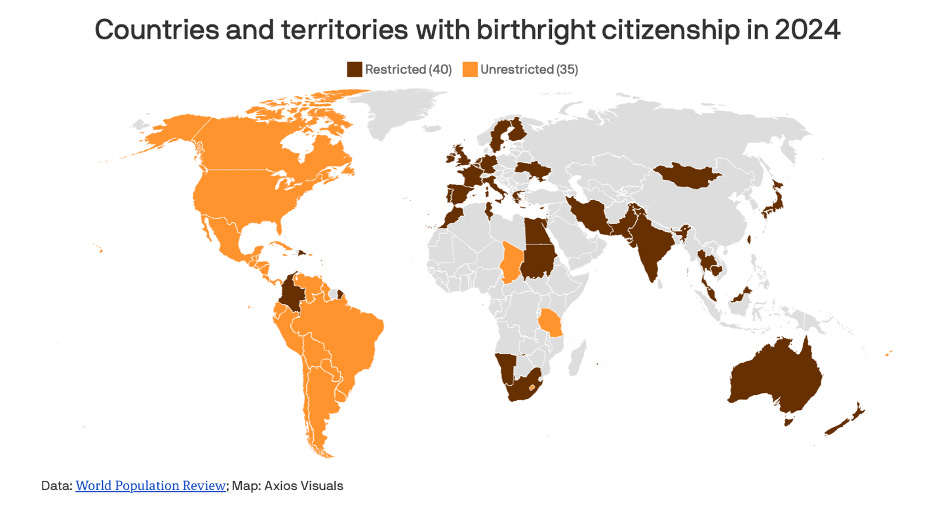

Anti-immigration activists on the right like to assert that the United States is alone in foolishly granting automatic citizenship to all people born on American soil, regardless of the immigration status of the child’s parents. But that isn’t true. Birthright citizenship is extremely rare across much of the world. But that isn’t the case in the Americas, from Canada on down through the nations of South America, where it is very much the norm.

With certain exceptions connected to foreign diplomats, slaves originating from Africa, and the Native American population of the continent, a version of jus soli prevailed in the United States from the beginning. After the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868, its citizenship clause tended to be interpreted as a codification of the longstanding practice of granting automatic citizenship to all children born on American soil.

This reading of the amendment received strong confirmation in 1898 from the Supreme Court, when it rejected the government’s argument that Wong Kim Ark, a man born in California to parents of Chinese immigrants, was not a citizen. In his majority opinion, Justice Horace Gray argued that the 14th Amendment “affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens.”

In the Nationality Act of 1940, and then in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 that superseded it, Congress built on the majority opinion in United States v. Wong Kim Ark to codify its understanding of birthright citizenship. In the decades before and since that time, countless millions of people born in the United States to non-citizen parents have claimed American citizenship under these provisions.

Dissenting Opinions

When people dismiss the legitimacy of Trump’s executive order, they typically do so by pointing to this tradition: the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment; Wong Kim Ark; and the 1940 and 1952 laws. How could it be that all of these documents, rulings, and laws—and acts undertaken on their basis—could have been mistaken when no one until July 2018 even thought to question their validity?

July 2018 is when former Trump 1.0 official Michael Anton published an op-ed in the Washington Post arguing that the citizenship clause has been misconstrued. Interpreted correctly, Anton claimed, it confers automatic citizenship only on children of American citizens. Others must consent to join the pre-existing social compact and be positively invited to do so by those who already belong to that compact. Trump’s second-term executive order eliminating birthright citizenship grows out of these arguments.

It turns out, though, that these arguments didn’t originate with Anton. Writing in dissent from the Supreme Court’s 1898 decision—Wong Kim Ark was decided 6-2—Chief Justice Melville Fuller claimed that Wong Kim Ark could not be a U.S. citizen because his parents were barred by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 from becoming American citizens. This kept them citizens of China who owed a duty to the emperor of China; they therefore could not be “completely subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, as stipulated in the relevant passage of the 14th Amendment. This meant that conferral of citizenship on their son could not be considered automatic upon his birth. He would have to apply for citizenship, and his application could well be rejected.

As scholars Peter Schuck and Rogers Smith argued in a controversial 1985 book, and then in a 2018 revisiting of their claims, this reading of the citizenship clause was not unique to Fuller. On the contrary, it was the expression of a longstanding tradition in American history that emphasized a “consensual” view of citizenship in which both the individual and state actively work to shape the political community.

Birthright citizenship, by contrast, descended from an older, “ascriptive” model rooted in English common law in which people became automatically subject to the king at birth. Schuck and Smith didn’t argue that either view was the right one, merely that neither was the self-evidently correct reading of the citizenship clause. Even though the ascriptive model of birthright citizenship had prevailed since the ratification of the 14th Amendment, Congress had the power to affirm the alternative, consensual view (and thus eliminate birthright citizenship) if it chose to.

As Rachel Morris explained in a recent article in the New Yorker about the strange afterlife of the book by Schuck and Smith, neither author considered himself a conservative nor thought that Congress should make such a change—merely that it could. Yet their claims were quickly seized upon by anti-immigration activists and then, decades later, by hard-right scholars at the Claremont Institute, and finally by the second Trump Administration.

The Endgame for Birthright Citizenship

In other words, if the Supreme Court’s conservative majority wants to hand Trump a victory on birthright citizenship, there is history and scholarship they can rely on to make their case. At least up to a point.

Where I suspect even the most stridently conservative justices may opt for restraint is in granting the president the power to eliminate birthright citizenship by executive order. Schuck and Smith talked of Congress redefining citizenship, not the head of the executive branch. Assuming the high court doesn’t simply use Barbara v. Trump to slap down the administration’s ambitions in this area, I suspect they will come down roughly where Schuck and Smith did: If Republicans want to redefine citizenship in the United States, they need to do it via the people’s representatives in Congress.

Given that Barbara v. Trump will be handed down at the end of the Court’s current term, that will leave Congress, with its razor-thin Republican majority, just a handful of months in which to attempt such a move before the party, in all likelihood, loses control of the House, and possibly the Senate as well, in 2026. This almost certainly means Republicans will need to return to fight another day, after they’ve won back control of Congress in a future election, to accomplish what Trump set out to do on the opening day of his second presidency.

That might sound like a loss for Trump and the MAGA right. But if the Supreme Court really does point the GOP toward a viable path to eliminating birthright citizenship in the not-too-distant future, that should be seen as a major victory for the political right in this country—one that will be directly traceable to Trump’s willingness to put the issue front-and-center in his Inauguration Day executive order.

In that respect, and in the longer run, Trump and his MAGA movement could well end up winning despite losing.

Damon Linker writes the Substack newsletter “Notes from the Middleground.” He is a senior lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior fellow in the Open Society Project at the Niskanen Center.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

This is one of the better essays on this subject that I have read. The challenge with most every controversy is that extremism begets extremism. The purpose of the 14th Amendment was to prevent southern racists from denying citizenship to black people who might be second, third, or fourth generation Americans. The claim was that if you were not considered a citizen when you were born, or your parents weren’t, then you do not have automatic citizenship.

This is a far cry from people breaking the law to come to America, or giving birth in a hotel or an airport. The children of permanent residents are somewhat more complicated.

Unfortunately , extreme views on the 14th Amendment have made this a question of presidential power rather than one of reason and justice. The current interpretation is untenable and it would be entirely appropriate for the Supreme Court to clarify the law.

We saw similar challenges after Brown v. Board of Education. Ultimately, CRA ‘64 provided the courts and the justice department the teeth to enforce the court’s ruling.

I hope that is not necessary here, but I expect that it will be. I would prefer for the middle ground to prevail, pun I tended.

This is just sane-washing. We don't have to pretend that legal scholars making arguments against ius soli are honest disinterested reasoners. The conservative majority of the Supreme Court decides what it does because it can, it is already beyond doubt that they are not an impartial institution