Machiavelli Would Hate Trump

He was one of the greatest defenders of republican government and the rule of law.

It’s an occupational hazard of being a philosopher that you may one day end up being associated with ideas that are the precise opposite of what you actually argued—or which, at the very least, ignore the most important aspects of your worldview. Friedrich Nietzsche is doomed to be associated with a kind of moody adolescent nihilism he would certainly have rejected. Albert Camus is constantly lumped together with his frenemies, the French existentialists. Persuasion’s own Francis Fukuyama is still battling the false charge that he claimed there would be no more historical events after 1989.

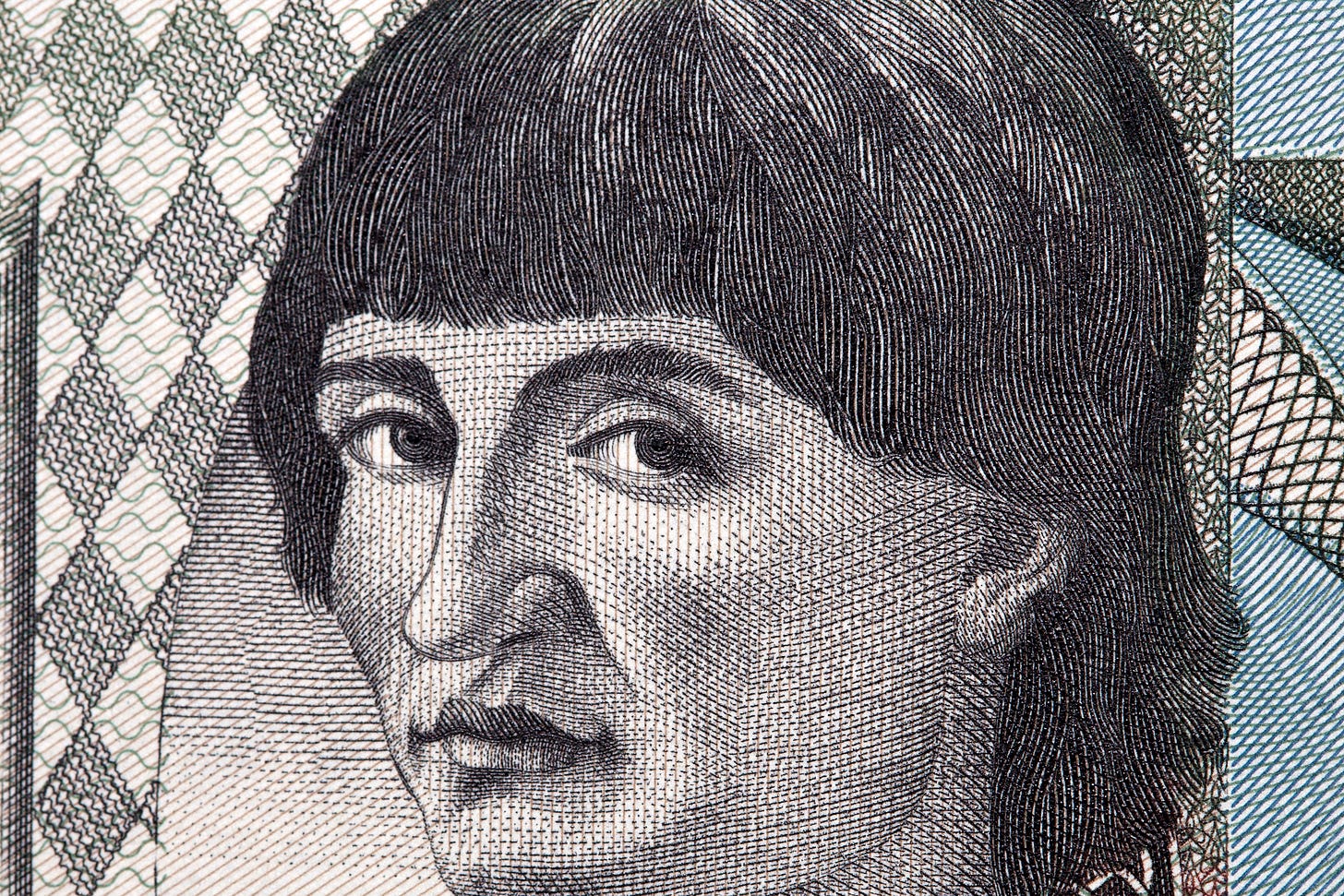

To this pantheon of the misunderstood we can add Niccolò Machiavelli. In the popular imagination, Florence’s most famous son stands for an extreme variety of realism, an ethic of “might is right” that justifies almost any action based on the expected results. And yes, Machiavelli’s best-known work is The Prince, published in 1532, in which he offers advice to rulers seeking to consolidate their power over Italy’s city states. When we think of Machiavelli, we think of hard-nosed maxims contained in that work such as “It is much safer to be feared than loved” and “Men should be either treated generously or destroyed.”

With Donald Trump back in power, it seems natural that commentators turn to The Prince to explain the particular ruthlessness of his new administration. It’s not hard to find articles using The Prince to explain why Trump is the Machiavellian genius of our time.1 One of the most compelling in this genre was recently published in these pages by Jeff Bleich, who argues that Trump’s actions “have been a deliberate and coherent application of Machiavelli’s 500-year-old playbook for turning a democracy into an autocracy.” He points to how, among other things, Trump has rained fire and fury against former-allies-turned-rivals, very much in line with Machiavelli’s advice to the prince about consolidating his power. We might also add the fact that Machiavelli was obsessed with national glory, and would likely have admired Trump’s foreign policy doctrine of aggressively focusing on America’s sphere of influence in the Western hemisphere.

Nevertheless, there are compelling reasons to think that, despite Trump’s evident Machiavellian realism in some domains, Machiavelli would have hated Trump and everything he stands for. A few years after The Prince, he wrote the Discourses on Livy, a commentary on the first ten books of Livy’s History of Rome, which is generally taken to be a more faithful presentation of his fundamental views. These views were small-r republican in nature; if you squint, they were even fairly philosophically liberal. They form part of a tradition stretching back to ancient Rome that was to influence the American Founding Fathers and inform many early liberal conceptions of freedom. While Machiavelli certainly did write his famous “mirror for princes”—hoping in part that by doing so he would convince the Medici to give him a job—he made no secret that his favored form of government was not a principality but a law-bound republic, which he considered to be both pragmatically and morally superior.

If The Prince is regarded as something of a guidebook for populists, the Discourses can be considered an anti-populist manifesto. The term “populist” is only mildly anachronistic here: the word has its origins in the Roman populares, the faction who in the first century BC claimed to stand on the side of the people against the patrician senate. Machiavelli makes clear that he believes the populares led to the “ruin of Rome” and set the stage for the death of the republic and the advent of Caesar. Why? Because they and their predecessors claimed to be friends of the people while secretly working to undermine their liberty.

Take this anecdote about Spurius Cassius, a man who foreshadowed the populares by attempting to bribe the people through the promise of economic redistribution. Machiavelli recounts that, “Being an ambitious man, this Spurius wanted to seize extraordinary authority in Rome and to gain the support of the plebeians by doing them many favors.” But at that time, the people were not yet corrupt, with the result that “when Spurius spoke to the people and offered to give them the money that had been obtained from the grain imported by the state from Sicily, they absolutely refused, in the belief that Spurius was trying to give them the price of their liberty.”2

What’s important is not that Spurius tried to redistribute resources to the people. It’s that he did so, according to Machiavelli, in contravention of the laws and in order to increase his own power. This theme crops up again and again in Machiavelli’s discussion of tyrants and aspiring tyrants, from the short-lived decemvirs of the fifth century BC to the populares of the late republic to Caesar himself. What Machiavelli condemns most is the domination of particular men. What he praises most are moments when “safeguards were put in place to make [leaders] unable to abuse their authority.”

We can reconstruct a number of principled arguments in the Discourses for why populism is corrosive to republican government, and why it should be rejected by anyone wanting to safeguard liberty.

First, populism threatens the rule of law. The law, Machiavelli believed, is the essential prerequisite for freedom. Its coercive power prevents others from infringing on our liberties, from engaging in corruption when in a position of authority or instituting strongman rule. The law can also be used to balance the voices of the rich and the poor by instituting a bicameral legislature in which each class has the power to keep the other in check. It furthermore serves as a salve against public anger: if people trust that the rules of the game apply equally to the man of great standing and to the man of few means, they are less likely to view the system as rigged. Finally, the law replaces the chaos of private, personal vendettas, so that one can “enjoy one’s possessions without worry [and] feel no fear for one’s own safety.” This allows the state to reap the fruits of an ambitious and active citizenry who undertake their various projects in peace.3

These are all familiar arguments for the benefits of the rule of law. It is striking to hear them come from a writer like Machiavelli, whose thought today is interpreted in a bastardized form that amounts to little more than “do whatever it takes to succeed.” But Machiavelli believed that republics only thrive when rulers and citizens don’t do whatever it takes to succeed. He argued that if private interests compete for influence over the institutions of the state, bending or rewriting the laws to serve short-term aims, corruption and servitude are the inevitable result. As the historian J.G.A. Pocock put it, “the truly subversive Machiavelli was not a counselor of tyrants, but a good citizen and patriot.”

But Machiavelli went further. Like most republicans in the Roman tradition, he assumed that the greatest corrupting influence on the state—and on independence of thought itself—is money. Money makes people selfish: if their wealth is tied up in land or commerce and they have a personal stake in the way these things are taxed or regulated, they are hardly going to be impartial judges of the public good. The wealthy magistrate must not be allowed to bring their own financial interests to bear in the process of lawmaking, nor to bend the law to provide “special favors” to their allies. A polity in which lawmakers organize a city “according to the needs of their own faction” is, for Machiavelli, little better than slavery. The art of politics therefore consists in finding ways to cultivate the virtue both of a citizenry that is equipped to withstand the siren call of populism and of a lawmaking class that governs with a view to the common good rather than the good of a particular faction or interest.

In this regard, Donald Trump and his allies are the embodiment of everything Machiavelli hated. He would have been suspicious from the get-go of a billionaire prince who appointed another billionaire (Musk) as his most important ally and lieutenant. He would have been distraught when those billionaires started giving out vast sums of money to supporters during an election; when they replaced impartial public servants with ideological allies; when they pardoned criminals who had attempted to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power (having risen up against the laws in order to keep one of these powerful men in office); and when they threatened to disobey any judge who stood in their way. These actions are textbook corruption according to Machiavelli’s thought.

The caveat here is that populism, of course, is not without its legitimate basis: this was true in republican Rome, in Machiavelli’s time, and it is true today. The populares could point out that the senate was hardly above corruption and special favors, and that there were good reasons for wanting to increase the voice of ordinary people. Likewise, today, there are real problems with the system Trump and Musk are trying to dismantle. The rule of law in America has grown into something more closely resembling rule by regulation, beset by sclerosis and inaction. And the political class against which Trump rails can hardly deny accusations that it is insular and elitist.

But as Machiavelli knew centuries ago, the populist cure is worse than the disease—especially when it is administered by rich and powerful men who exhibit every sign of megalomania, and are willing to run roughshod over the established order to get what they want. Populism is premised on a model of the relationship between ruler and ruled that is corrosive to the fair application of law. It replaces universal national symbols with the personalism of the leader and threatens to ever expand the role of money in politics. It undermines any hope that the system is oriented toward the common good rather than the good of whoever happens to be in power at the moment. And it does all of this by perverting a form of government—republicanism—that, as Machiavelli recognized, stands in direct contradiction to the populist project of accumulating personal power through elected office while claiming to speak on behalf of the people.

Far from being the Machiavellian genius of our time, Trump’s actions would make Machiavelli weep.

Luke Hallam is senior editor at Persuasion.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I keep seeing claims that Trump himself has read and admired The Prince, though I can’t find any hard evidence for this.

Emphasis mine.

As Quentin Skinner points out, Machiavelli’s discussion of the law is informed by his deeply pessimistic account of human nature. Only by instituting a comprehensive set of laws that preempt almost any situation can a republic hope to overcome individuals’ natural corruption and propensity to selfishly seek power for themselves over the good of the community.

Excellent tribute to stoic and republican virtue. Trump cannot possibly have read Machiavelli. I doubt if he’s read the US Constitution, which might be a more realistic first step in his political education

I imagine someone once told him Machiavelli was “tough,” so he assumed he was a sort of Renaissance Putin.

Absolutely brilliant article.