Open Societies Are Stronger Than They Appear

It is a recurring fallacy to underestimate democracy’s resilience.

Across the modern New Right, or the climate-activist left, there is a widespread belief that the very characteristics which were once hailed as America’s strengths are weaknesses. Pluralism, it’s often said, makes our society disparate and fractious. The rule of law hampers the government’s ability to solve big problems. And erratic election results remove leaders before they have a chance to implement lasting change.

Some populists, fearing weakness more than totalitarianism, want to eliminate the diversity of our society in favor of unity. There’s a tendency among environmental activists to believe that the scale of the climate crisis requires doing away with free choice and democratic governance.

But in all cases, these critics mistake strength for weakness. Many on the New Right in particular confuse projection with actual strength. They imagine that our enemies are about to eclipse us, that Russia and China will lead the future as America and the West inevitably decline. But real strength tends to be more about flexibility than unity. Open societies tend to be more adaptable than closed ones. And as we head into a period of history in which the lure of the closed society appears to be irresistibly growing, it’s worth remembering that we have all seen this movie before in the failures of closed societies, whether fascist or communist, throughout the 20th century. Now is a good time to consider how tough open societies really are—and why there is such a persistent tendency to underestimate their resilience.

The polymath Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a derivatives trader and philosopher of uncertainty, gives the example of the mouse and the elephant. The elephant dwarfs the mouse. But if an elephant falls from twice its own height, it breaks all of its bones. If the mouse falls from ten times its height, it runs away easily.

Because we evolved in an environment in which size connoted strength, we mistake the size of the authoritarian government for strength. We don’t see the brittleness of the elephant’s bones. The idea is that our common sense—our primitive brain—can so often mislead us in the highly-complex modern environments that we find ourselves in, and a different kind of thinking is called for that emphasizes redundancy, diversification, openness, and, maybe most importantly, a deep layer of humility.

It’s certainly striking that we see the same errors continually recurring. Throughout the 20th century, prominent commentators believed that the free world was declining and autocracy was the future. At every turn, they were proven wrong, and yet the same tired predictions keep cropping up. During the Cold War, many anticommunists believed they were on the losing side. Many on the left believed the USSR had a conviction and purpose that the West couldn’t hope to match. In the 1920s and ‘30s, American journalists and academics hailed both communism and fascism. The great investigative reporter Lincoln Steffens famously returned from the Soviet Union claiming he had “been over into the future and it [worked].” He also said that God “formed Mussolini out of the rib of Italy.” Mussolini in particular was beloved by American intellectuals from Columbia University’s president to muckraking journalists such as Ida Tarbell and Anne O’Hare McCormick.

Even opponents of totalitarianism thought it might be inevitable. James Burnham’s 1941 The Managerial Revolution (now popular in some corners of the New Right) contains some of this fascination with authoritarian power projection. Burnham assumed that capitalism would give way to a new “managerial class” that would impose centralized planning. Elsewhere, Burnham juxtaposed the “fanaticism” of the Nazis with the supposed “apathy” of Britain and France. Throughout his work, he worried that free societies would prove too weak to resist creeping despotism.

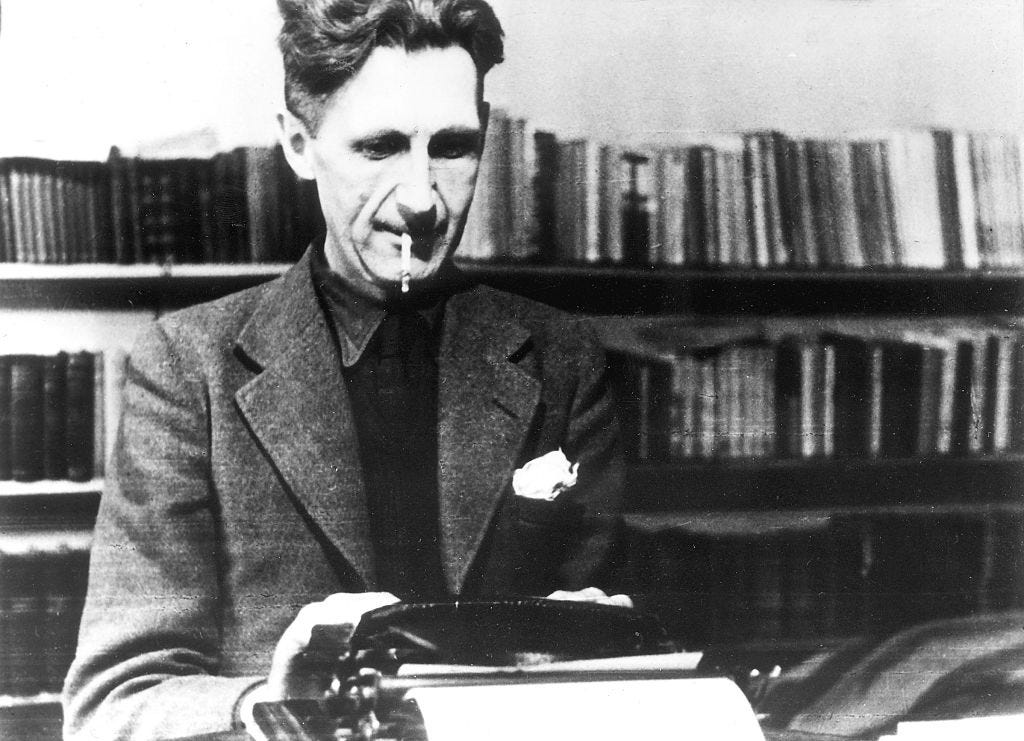

But Burnham should largely have been discredited by events in his own time, as George Orwell noted in his 1946 essay “Second Thoughts on James Burnham.” Orwell wrote:

Power worship blurs political judgement because it leads, almost unavoidably, to the belief that present trends will continue … Such a manner of thinking is bound to lead to mistaken prophecies, because, even when it gauges the direction of events rightly, it will miscalculate their tempo. Within the space of five years Burnham foretold the domination of Russia by Germany and of Germany by Russia. In each case he was obeying the same instinct: the instinct to bow down before the conqueror of the moment, to accept the existing trend as irreversible.

The polarity between Burnham and Orwell mirrors what we see today in writers who argue that America is a spent force and “post-liberalism” is needed to revitalize our sclerotic culture. Thinkers like Burnham saw the trends of the moment—the weakness of democracies, the apparently inexorable rise of the totalitarian states—and assumed they would continue forever. It is not difficult for the contemporary equivalents of Burnham to see division and balkanization in America—but they repeat Burnham’s mistake when they assume these trends will continue in a straight line and lead to our downfall.

History, however, doesn’t work like this. Crises are usually unexpected and so too are their solutions. A dynamic and vibrant society which allows for a range of institutions is more likely than a top-down society to contain within it elements which will resist a crisis and even grow stronger.

In his 2012 work Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder, Taleb attempted to account for this seeming paradox by contrasting the relatively simple environments in which “common sense” developed with the far more complex environments that we now find ourselves in and in which “black swan” events are ever more likely and have to be accounted for with “antifragile” systems. A perfect example would be the common-sense way in which “systematically preventing forest fires from taking place ‘to be safe’ makes the big one much worse.”

So many of our policies then are held hostage by our outdated “common-sense” thinking, which tends only to make our societies that much more fragile. We think we’re protecting the economy when we impose greater state control, but we’re actually introducing barriers to adaptation that drag us down when external or internal shocks make adaptation necessary. We imagine that centralizing vast powers in a single authority creates a stronger society—which is exactly the wrong thing to do in a hyper-complex environment. We hope that by growing our government, we will be able to meet the challenges of the 21st century. But the more we try to control our economy, especially from the top down, the more we weaken it and set it up for failure. Taleb achieved a sort of proof-of-concept for his views with his 2007 book The Black Swan, which seemed, in retrospect, to be one of the better accounts of the financial crisis that hit the next year—demonstrating the limitations of “optimized” thinking and the inevitability of transformative “black swan” events.

The antidote, in Taleb’s view, is to get away from common sense and the primitive need to control and to accept a degree of randomness and volatility. The free market—the antithesis of centralized planning—is not only more fluid and flexible and can therefore better respond to shocks, it also avoids the “doubling-down” common in highly-regulated markets which can make minor crises systemic. Redundancy, distribution of power, and permission to innovate can make a society robust to the same shocks that would tear apart a more ironclad, muscle-bound system.

We can see some of these dynamics playing out in the spreading contemporary animus towards the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution certainly seems less than a fully-optimized system of managerial control, and thinkers on both the left and right have argued that, accordingly, the Constitution isn’t up to the challenges of the 21st century. But, with Taleb to help guide us, we can see that that’s exactly the wrong approach and underestimates the core strengths of the Constitution. The Constitution establishes a federal system of overlapping sovereignty, with a supreme national government sharing power with separate state governments whose power isn’t delegated by the national government. It is precisely this decentralization (similar to, as Taleb notes, the federalism of Switzerland’s cantons) which makes American society robust to the sort of rapid regime change we see in various parts of the world today. Or, as James Madison put it in Federalist 10, “any… improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the Union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire State.”

The American Founders studied classical and Enlightenment philosophy. But they also studied the history of republican forms of government and why they failed, in order to understand how those failures might be averted. The Constitution they created is now the oldest in the world.

Taleb writes of “the Lindy effect” that technologies which have already survived the longest are the likeliest to survive into the future, and the newer a technology, the more quickly it will become obsolete. That our Constitution has survived as long as it has says something about its durability. But its durability is not a mere accident. Its structure is more robust and resistant to shocks than most other constitutions. It is a model of antifragility, of a system with redundancies and apparent inefficiencies built into it—and the features that so often prove unpopular, that are less than fully “optimized,” are precisely those that help ensure its resilience.

There is decentralization. Also, the fact that change is slow. And frequent elections mean that coalitions rarely reign long enough to enact their will, unless they represent a true and lasting majority of the popular will in a majority of the states. Where an authoritarian leader can decree that a nation will pursue a particular direction, a society like ours requires buy-in from a sustainable majority, with the consequence that a new societal direction must be deeper and broader (and therefore more real) than in a top-down society in which ephemeral power-projection can substitute for actual change at the ground level.

The resilience of the Constitution offers a useful model for the challenges to come in the next decades. Because we cannot predict the future, we cannot, as Taleb argues, prepare for shocks. The best we can do is to ensure that our systems contain enough redundancy and adaptability to handle them.

The critics of free societies are right when they say that unions, businesses, churches, civic organizations, universities, non-profits, and thousands of other institutions pull us in different directions. They are right when they say that autocracies have unity that we lack, whether they point to Putin’s Russia or Mussolini’s Italy. But they are wrong to imagine that diversification makes free societies weak, or that streamlining renders closed societies strong. Instead, it is free societies that are set up to survive and thrive in an uncertain future, and closed societies which mask weakness.

That isn’t to say that free societies will always defeat closed ones, nor that history always moves in the direction of greater freedom. Humans will probably always make the same mistakes we have throughout history. But for those today who want to ditch freedom in the name of strength, don’t be fooled by the illusion of power.

Ben Connelly is a writer and long-distance runner living in Virginia. His Substack is Hardihood Books where he writes a mix of fiction and nonfiction.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

As someone with decades of experience in organizational design and leadership, the simple truth is that without a unified and binding organizational culture the organization will become too fractious and ungovernable. Without this, the organization becomes much too difficult to make needed change and course correction. Productivity suffers.

However, the same risk exists on the other side of this principle where the work culture becomes too rigid and hierarchical, it stifles needed creativity and the ability be nimble in response to needed change.

The key is to do both... to have a binding culture that is limited to being foundational and not more than it needs to be. And to welcome diversity of experience, thought and perspectives that result in the outcome of people being better than the sum of their parts.

Because these two things are always in conflict with each other, that is were effective leadership is important. Good leaders ensure a balance.

The US has been infected with terrible leadership for decades until Trump was elected to restore balance from the extreme pull of previous politicians and government officials toward the multiculturalism globalism side. The primary motivation for this has been money... trillions being made on Wall Street chasing corporate profit maximization and corporate shareholder return maximization. This has benefited the top10% at the expense of everyone else, but the top 10% - the Professional Managerial Class - wants more and thus is determined to stop Trump from implementing the needed balance.

Just look at it today... unemployment is increasing and yet the stock market keeps hitting new highs.

The cry of "nationalism" and "fascism" are just hyperbolic lies to try and prevent the return to a balanced country with a foundational culture and set of moral values. However, the pull back from the clearly failed multiculturalism globalist project is a threat to the big money oligarchs that are primarily supported by the Democrat party machine. And so they will keep up the myth that "diversity is strength" when the evidence that the best countries to live are those with a more homogeneous base culture that demands immigrants assimilate to.

Republics are invariably more powerful than kingdoms. They are almost never killed, but very often they suicide.