Our Top Books of 2025—Podcast Edition

We interviewed them. You listened. Here are the authors whose books we’ve loved reading this year.

Richard Aldous (Host of Bookstack)

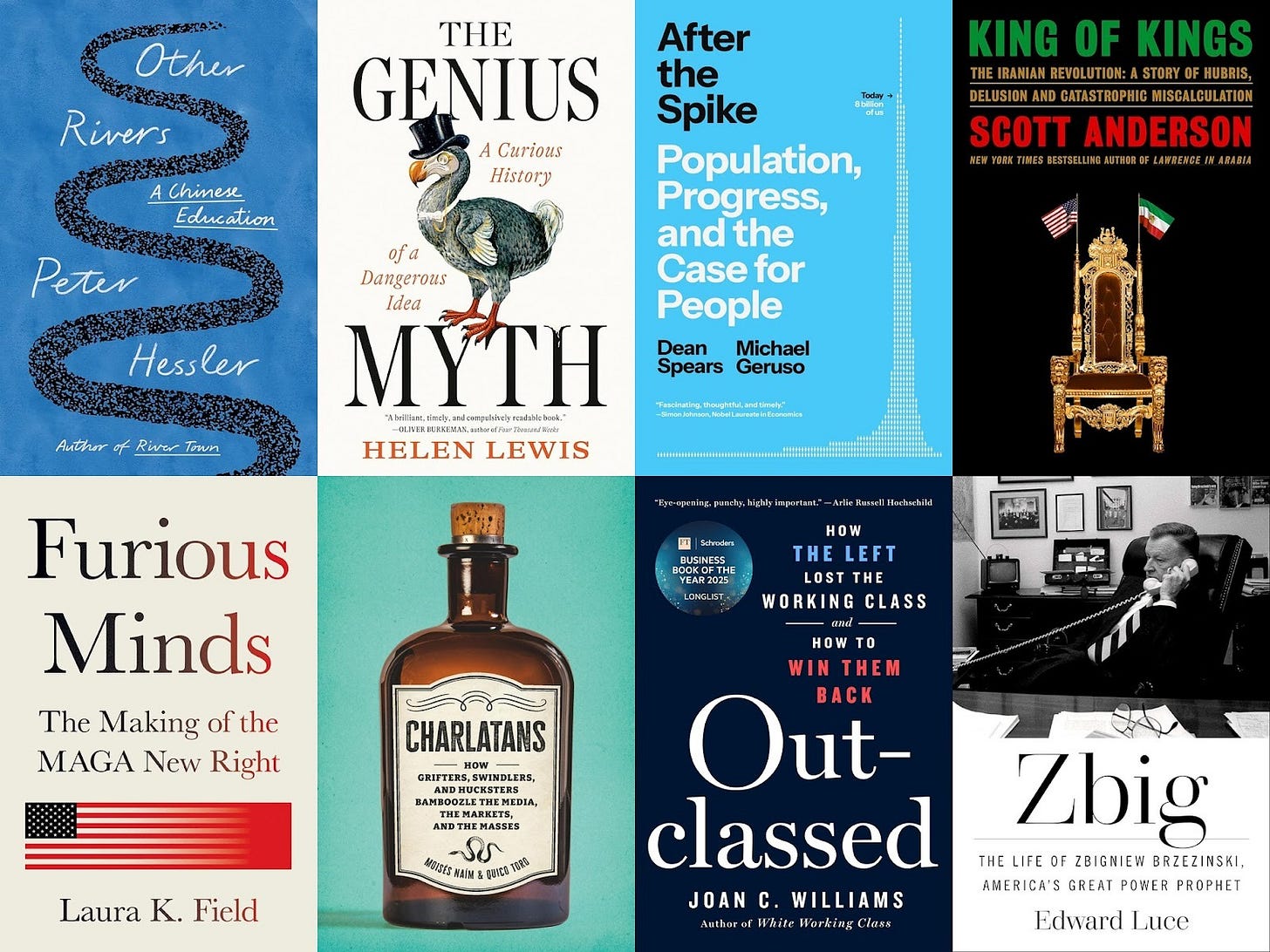

We’ve had some cracking new books on Bookstack in 2025, not least by Simon Ball on political assassination, Tevi Troy on the relationship between business and politics, and Joan Williams on why the Democratic Party seems to have abandoned the working class. But I’ve long been fascinated by President Carter’s national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and now finally he has the biography he deserves. Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet by Edward Luce brilliantly captures Brzezinski’s originality as well as his coruscating wit. Brzezinski was a contemporary of Henry Kissinger, and like him was an emigrant to the United States. Together they were leading figures among that rising breed of scholar-politicians of the postwar period—“all knowing grand viziers to the sultans of their time.”

While conventional wisdom in the late sixties and seventies was that the United States was going to the dogs, Brzezinski predicted a new age of American dominance. He also rejected the popular convergence theory, believing instead, as President Reagan would, that U.S.-led capitalism would grind Soviet communism into the dirt. That kind of originality made Brzezinski useful to people like the Rockefellers and, most of all, to the rising Democrat Jimmy Carter, who appointed him national security advisor in 1977.

Brzezinski was often criticized as a cynical realist in the vein of Eisenhower’s secretary of state, John Foster Dulles. His typically blunt response was that “world politics is not a kindergarten.” Carter became increasingly offended by Zbig’s realism, preferring instead to stake out the moral highground. Read another Bookstack author, Scott Anderson, in King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution: A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation, for a day-by-day account of how it worked out when Carter’s idealism ran into the realism of Ayatollah Khomeini. It’s a reminder that even the most brilliant political advisor is ultimately only as good as the principal he serves. But in Zbig, at least, the life of Zbigniew Brzezinski also makes for an exceptional political biography.

Leonora Barclay (Head of Podcasts)

My favorite part of my job is to read so many books—and to see if the authors live up to my expectations of them. So I greatly enjoyed Helen Lewis’ The Genius Myth, which explores how our choice of who we place on a pedestal has changed over time, and what this tells us about our society.

Lewis argues that, since the Middle Ages, we’ve seen “genius” as being a special kind of person—a Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, a William Shakespeare, a Steve Jobs. We love our geniuses to have some sort of tragic or complex life, such as dying young, being addicted to something destructive, or having a love life that requires a diagram to understand. Jane Austen, for example, lived a disappointingly dull life, which has led to her being excluded from some compilations of geniuses.

Despite these challenges, we persist in hoping that geniuses can share their greatness with us. Lewis uses the example of the organization Mensa—the world’s largest high-IQ society—which initially thought it could poll its membership on leading issues of the day, so the world could gain from their insights. Unfortunately, outside their individual subjects of expertise, the Mensa members turned out to be just like everyone else.

This human desire to put someone on a pedestal cropped up again in my other favorite book this year, Charlatans by Moisés Naím and Persuasion’s own Quico Toro. Traditionally, they argue, charlatans were pretty limited to either selling health products or “get rich quick” schemes. However, driven by the Internet, our near-universal screen addiction, and corresponding loneliness and social isolation, we now live in a “charlatanogenic” culture, with lots of opportunities to idolize and be scammed: the promise of love, the meaning of life, connecting with aliens, and much more.

Of course, one particular charlatan in our culture springs to mind, and Naím and Toro explore the impact of charlatans in politics too, arguing that the tactics Donald Trump used even before running for office (“the big, attention-getting promises with scant follow-up, the serial deception, and the obsession with money”) echo those of history’s biggest charlatans. A depressing observation, but a great read!

Francis Fukuyama (Host of Frankly Fukuyama)

The book I’d like to feature is Furious Minds by Laura K. Field. This is a book that deals comprehensively with the intellectual origins of the MAGA right. I was particularly interested in interviewing Laura because of her background. She was trained as a Straussian—that is, by second and third generation students of Leo Strauss, the political theorist who wrote about the “crisis of modernity” and published dense commentaries on a host of philosophers including Maimonides, Hobbes, Machiavelli, Xenophon, and many others. I myself have a similar background, having been a student of two teachers Laura writes about, Allan Bloom at Cornell and Harvey Mansfield at Harvard.

What I wanted to learn from Laura was where a certain group of Straussians went wrong, such that they ended up becoming big supporters of Donald Trump. This group includes John Eastman, Michael Pack, and Michael Anton—the latter the author of the famous “Flight 93” article in The Claremont Review of Books, which claimed that the United States would continue in a terminal death spiral unless voters rolled the dice and voted for Trump in 2016.

Many people are aware of the divide between so-called “East Coast” and “West Coast” Straussians, the latter associated with the Claremont Institute and Strauss’ student Harry Jaffa. Jaffa was the author of the excellent book Crisis of the House Divided on the 1858 debates between Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen Douglas. In that book, he argued that Stephen Douglas’ arguments for states’ rights and federalism in the U.S. Constitution were ultimately trumped by the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal,” and that, contrary to Douglas, democratic majorities of white voters in the South could not legitimize slavery. Yet today, Claremonters are echoing Douglas in their calls for a return to the “original” Constitution, and downplaying the promise of equality in Jefferson’s Declaration.

Laura’s book goes way beyond the Straussian world, however, to cover other right-wing writers like Curtis Yarvin and Costin Alamariu (a.k.a. “Bronze Age Pervert”), who are much more Nietzschean. In my interview with her, she went out of her way to defend the general Straussian approach to teaching political philosophy, and expressed gratitude to her teachers for opening her eyes to the great Western philosophical tradition.

In this I very much agree with Laura. Like many second-generation students of Strauss, I benefited enormously from my classes with Bloom and Mansfield. I can easily recognize some of the blinkers that such an education induces (such as disdain for social science and empiricism more generally). But nonetheless I am grateful for having received a true liberal education. Laura’s book is an excellent introduction to that world, as well as an alarming account of what has happened to America in the age of Trump.

Yascha Mounk (Host of The Good Fight)

This year has been consumed by the radical antics of the Trump administration. As a result, I have spent more of my time than is probably healthy looking at the latest headlines. But that is also why I have particularly enjoyed the writing of podcast guests that have expanded my horizons: ones that inspired me to think about broader themes which will remain relevant long after depressing outrages—like Trump’s recent decision to add his name to the Kennedy Center—are (hopefully) long forgotten.

A lot of smart and educated people I talk to still worry that the world is headed toward a crisis of overpopulation. But as Dean Spears and Mike Geruso explain in their book After the Spike, this is a mistake. In most countries, a low fertility rate is the more pressing problem today—and while the world’s population will continue to rise for a few decades, it is likely to crash soon after. Spears and Geruso are hardly the first to make this point; but this is the best primer on this topic for a general audience I have found so far.

As faithful readers of these pages will know, another topic I have been thinking about a lot is China. Perhaps no writer about the country enjoys greater respect both within the United States and in China than Peter Hessler. His best-known book, River Town, written when Hessler was teaching English at a small university in a remote corner of Sichuan in the 1990s, tells the story of the Reform Era, when China, still desperately poor, was growing at a frantic pace. But it is his latest book, Other Rivers, written when Hessler returned to the province to teach in Chengdu, that I found to be more touching: it chronicles the lives of his former students, and contrasts their fates with that of a younger generation growing up in a country that is vastly more affluent—but also, in important ways, less full of hope.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I just started Paul Starr's American Contradiction. Has anyone else read it?