Text Is (Still) King

Why the written word will never die.

The hot new theory online is that reading is kaput, and therefore civilization is too. The rise of hyper-addictive digital technologies has shattered our attention spans and extinguished our taste for text. Books are disappearing from our culture, and so are our capacities for complex and rational thought. We are careening toward a post-literate society, where myth, intuition, and emotion replace logic, evidence, and science. Nobody needs to bomb us back to the Stone Age; we have decided to walk there ourselves.

I am skeptical of this thesis. As a psychologist, I used to study claims like these for a living, so I know that the mind is primed to believe narratives of decline. We have a much lower standard of evidence for “bad thing go up” than we do for “bad thing go down.”

Unsurprisingly, then, stories about the end of reading tend to leave out some inconvenient data points. For example, book sales were higher in 2025 than they were in 2019, and only a bit below their high point in the pandemic.

Independent bookstores are booming, not busting; at least 422 new indie shops opened in the United States last year alone. Even Barnes & Noble is cool again.

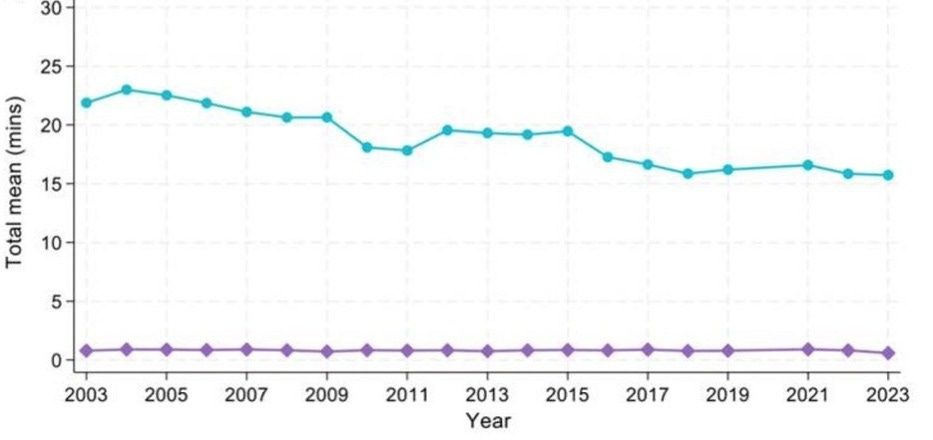

The actual data on reading, meanwhile, isn’t as apocalyptic as the headlines imply. Gallup surveys suggest that some mega-readers (11+ books per year) have become moderate readers (1-5 books per year), but they don’t find any other major trends over the past three decades. Other surveys document similarly moderate declines. For instance, data from the National Endowment for the Arts finds a slight decrease in the percentage of U.S. adults who read any book in 2022 (49%) compared to 2012 (55%). And the American Time Use Survey shows a dip in reading time from 2003 to 2023:

Ultimately, the plausibility of the “death of reading” thesis depends on two judgment calls.

First, do these effects strike you as big or small? Apparently, lots of people see these numbers and perceive an emergency. But we should submit every aspiring crisis to this hypothetical: How would we describe the size of the effect if we were measuring a heartening trend instead of a concerning one?

Imagine that Time Use graph measured cigarette smoking instead of book reading. Would you say that smoking “collapsed” between 2003 and 2023? If we had been spending a billion dollars a year on a big anti-smoking campaign that whole time, would we say it worked? Kind of, I’d say, but most of the time the line doesn’t budge. I wouldn’t be unfurling any “Mission Accomplished” banners, which is why I am not currently unfurling any “Mission Failed” banners, either.

The second judgment call: Do you expect these trends to continue, plateau, or even reverse? The obvious expectation is that technology will get more distracting every year. And the decline in reading seems to be greater among college students, so we should expect the numbers to continue ticking downward as older bookworms are replaced by younger phoneworms. Those are both reasonable predictions, but two facts make me a little more doubtful.

Fact #1: There are signs that the digital invasion of our attention is beginning to stall. We seem to have passed peak social media—time spent on the apps has started to slide. App developers are finding it harder and harder to squeeze more attention out of our eyeballs, and it turns out that having your eyeballs squeezed hurts, so people aren’t sticking around for it. It’s no wonder that, after paying $1,000 for a new phone, people will then pay an additional $50 for a device that makes their phone less functional.

Fact #2: Reading has already survived several major incursions, which suggests it’s more appealing than we thought. Radio, TV, dial-up, Wi-Fi, TikTok—none of it has been enough to snuff out the human desire to point our pupils at words on paper. Apparently, books are what some hyper-online people call “Lindy”: they’ve lasted a long time, so we should expect them to last even longer.

It is remarkable, even miraculous, that people who possess the most addictive devices ever invented will occasionally choose to turn those devices off and pick up a book instead. If I was a mad scientist hellbent on stopping people from reading, I’d probably invent something like the iPhone. And after I released my dastardly creation into the world, I’d end up like the Grinch on Christmas morning, dumbfounded that my plan didn’t work: I gave them all the YouTube Shorts they could ever desire and they’re still... reading!?

Perhaps there are frontiers of digital addiction we have yet to reach. Maybe one day we’ll all have Neuralinks that beam Instagram Reels directly into our primary visual cortexes, and then reading will really be toast.

Maybe. But it has proven very difficult to artificially satisfy even the most basic human pleasures. Who wants a birthday cake made with aspartame? Who would rather have a tanning bed than a sunny day? Who prefers to watch bots play chess? You can view high-res images of the Mona Lisa anytime you want, and yet people will still pay to fly to Paris and shove through crowds just to get a glimpse of the real thing.

I think there is a deep truth here: Human desires are complex and multidimensional, and this makes them both hard to quench and hard to hack. That tinge of discontent that haunts even the happiest people, that bottomless hunger for more even among plenty—those are evolutionary defense mechanisms. If we were easier to please, we wouldn’t have made it this far. We would have gorged ourselves to death as soon as we figured out how to cultivate sugarcane.

That’s why I doubt the core assumption of the “death of reading” hypothesis. The theory heavily implies that people who would once have been avid readers are now glassy-eyed doomscrollers because that is, in fact, what they always wanted to be. They never appreciated the life of the mind. They were just filling time with great works of literature until TikTok came along.

I don’t buy this. Everyone, even people without liberal arts degrees, knows the difference between the cheap pleasures and the deep pleasures. No one pats themselves on the back for spending an hour watching mukbang videos, no one touts their screentime like they’re setting a high score, and no one feels proud that their hand instinctively starts groping for their phone whenever there’s a lull in conversation.

Finishing a great nonfiction book feels like heaving a barbell off your chest. Finishing a great novel feels like leaving an entire nation behind. There are no replacements for these feelings. Videos can titillate, podcasts can inform, but there’s only one way to get that feeling of your brain folds stretching and your soul expanding, and it is to drag your eyes across text.

That’s actually where I agree with the worrywarts of the written word: All serious intellectual work happens on the page, and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise. If you want to contribute to the world of ideas, if you want to entertain and manipulate complex thoughts, you have to read and write.

According to one theory, that’s why writing originated: to pin facts in place. At first, those facts were things like “Hirin owes Mushin four bushels of wheat,” but once you realize that knowledge can be hardened and preserved by encoding it in little squiggles, you unlock a whole new realm of logic and reasoning.

That doesn’t mean every piece of prose is wonderful, just that it can be. And when it reaches those heights, it commands a power that nothing else can possess.

I didn’t always believe this. I was persuaded on this point recently when I met an audio editor named Julia Barton, who was writing a book about the history of radio. I thought that was funny—shouldn’t the history of radio be told as a podcast?

No, she said, because in the long run, books are all that matter. Podcasts, films, and TikToks are good at attracting ears and eyes, but in the realm of ideas, they punch below their weight. Thoughts only stick around when you print them out and bind them in cardboard.

I think Barton’s thesis is right. At the center of every long-lived movement, you will always find a book. Every major religion has its holy text, of course, but there is also no communism without the Communist Manifesto, no environmentalism without Silent Spring, no American Revolution without Common Sense. This remains true even in our supposed post-literate meltdown—just look at Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance, which inspired the creation of a Congressional caucus. That happened not because of Abundance the Podcast or Abundance the 7-Part YouTube Series, but because of Abundance the book.

I know that what we used to call “social media” is now just television you watch on your phone. I know that people want to spend their leisure time watching strangers apply makeup, assemble salads, and repair dishwashers. I know they want to see this guy dancing in his dirty bathroom and they want to watch Mr. Beast bury himself alive. These are their preferences, and woe betide anyone who tries to show them anything else, especially—God forbid—the written word.

But I also know that humans have a hunger that no video can satisfy. Even in the midst of infinite addictive entertainment, some people still want to read. A lot of people, in fact. 5,000 years after Sumerians started scratching cuneiform into clay and 600 years after Gutenberg started pressing inky blocks onto paper, text is still king. Long may it reign.

Adam Mastroianni writes the Substack Experimental History.

A version of this article was originally published at Experimental History.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I don’t agree with this article… but I am hopeful that I am wrong.

Your essay seems to imply that reading, text, and books are identical, but they are not. A long time ago I read a reasonable number of books. Then I largely switched to reading articles in scientific journals, listening to books on tape. Now I spend most of my reading time reading essays like yours online, along with other online stuff. So far as I can see, the medium plays a secondary role; what matters is text that is accessible and more or less stable/permanent. Your thoughts?