The Everyday Abyss

A report from Ukraine in the age of drone warfare.

Regular readers of Persuasion will know the story of Kateryna Kibarova, a Ukrainian resident of the Kyiv suburb of Bucha, who has been sharing searing updates on her life in Ukraine since the Russian invasion. (You can read each installment of her writing here.)

Shortly after we published her last report, Kateryna wrote to say that she had narrowly escaped a drone attack during one of Russia’s many recent air raids on the Ukrainian capital. What follows is her harrowing account of that incident, and an update on the daily challenges and small graces of life well into the third year of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

—David, Executive Director

by Kateryna Kibarova

When I last reported in March, we were all so hopeful that there would be a truce or that everything would finally be over. The very next night, Shahed drones struck three or four kilometers away from me. There was heavy damage. The drones hit buildings that had recently been rebuilt after being completely destroyed at the start of the invasion in 2022.

There’s now constant shelling, the likes of which we haven’t seen since the full-scale invasion began. For people coming back to Ukraine from overseas, it’s been a crazy shock. Many of them have probably decided to leave again.

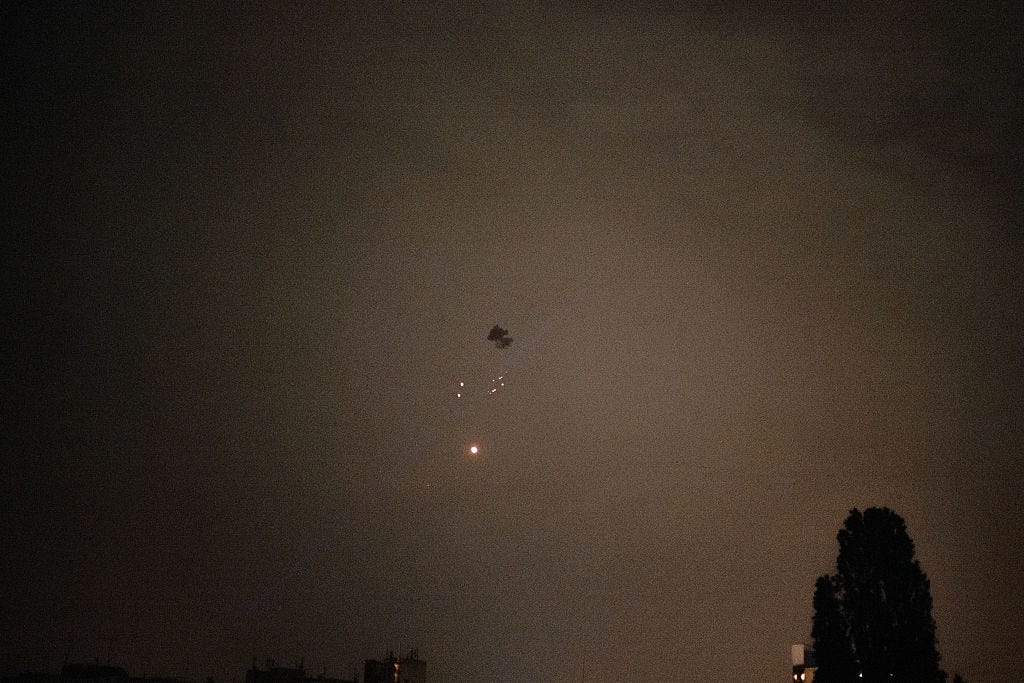

Last month, during one of these air raids, I wasn’t really paying much attention. I got out of my car in the store parking lot and started walking to the entrance. I heard what sounded like either a moped or a motorcycle going by. It didn’t seem at all unusual. But then I looked up and saw a huge drone flying directly overhead.

One of the anti-aircraft batteries opened fire. Naturally, people scattered. But I froze. There was nowhere to hide—no shelter, no subway, nothing. In such a moment, you find yourself in a state of confusion. You can’t predict which way the drone is flying and what's going to happen next. It’s simply horrific. There’s just no way to describe it in words.

Normally, I know exactly what to do, but this time I just panicked. The bullets from the air defenses started flying and the drone was circling overhead. I was out in the open, in the parking lot between the car and the store, and I was paralyzed. At a certain point I just crouched down, covered my head, and waited for the drone to be shot down.

After some time, the anti-aircraft battery downed the drone. I went back to the car, sat in the seat, and thought to myself “well, that could have been the end.” To think about how people, especially in frontline towns, live in such a state all the time—it’s pure horror.

Early in the war, after the occupation of Bucha, I went to a psychologist because I started having panic attacks. With the help of a counselor and medication, I made progress. Now the attacks have started again. After the incident with the drone, I got really scared. I just didn’t know what to do next, because life is, at this point, a state of utter grief. It’s a total abyss.

I’ve been advised to go to the forest, be totally alone, and listen to the birds singing. This is the kind of therapy that relaxes my nervous system and will, I hope, help me. Just feeling safe will be so therapeutic.

I’ve also been told that my nervous system could be relaxed with the help of special drugs. But I can’t take them: I have to drive to work, and I have a creative job, both of which aren’t really compatible with such medication. So, instead, I’m looking forward to a little trip to the forest in the western part of the country, where I turn off my phone, get off messaging apps, and take a break from working. This way, hopefully, I’ll finally be able to relax and my nerves will level out a bit.

Most people don’t go to counselors or to psychologists, and a huge number of Ukrainians have developed post-traumatic stress disorder. It’s a very serious problem that, unfortunately, people don’t recognize at first. You start to have some moments— insomnia, panic attacks—and you don’t realize that you have a real problem, one that requires special help. But these problems aren’t pretty, so people are afraid to talk about them.

There’s also the cost. An average visit to a psychologist, for an hour, costs about $40. If they’re a very good psychologist, they can cost $100 an hour. A grandmother’s pension is around $90 a month. So now only the people who have the money can access mental health care.

I read in an article that a very large number of military personnel who are released during a POW exchange come back and then die by suicide. And it’s precisely because they have post-traumatic stress disorder. What’s scariest is that their relatives can’t identify it. That is why it is necessary to take everyone, those who have been in combat and those who have been in captivity, to a psychologist to determine their degree of trauma. Everyone has it. If it is present in the civilian population, it is present in the military population.

On top of the PTSD, a lot of people who were in Ukraine at the beginning of the war suffered concussions. Like many, I didn’t know at that time what it was. A huge shell had exploded near me, and only when I went to the western part of the country, when we escaped from the occupation of Bucha, did I realize that I was feeling the effects all over my body: my vision began to split, my hearing was affected, I got headaches. It’s very serious.

We are constantly confronted with some kind of stress. For example: not long ago, a missile landed on a house in Svyatoshyno. In the morning I opened our business chat, and the first message there was “everyone is alive, no one was hurt.” This is what happens in our work chat—this is how we live. Some colleagues have kids in daycare, and when they go to work, it’s stressful for them to leave the kids elsewhere. When the kids in schools go into shelters it’s stressful for them. When an air raid siren sounds, they immediately start calling their children at school. We’re at the point where there is a drone attack every night, but no one takes special notice. No one’s even discussing that anymore. Everyone is used to it.

So each of us is in a state of stress, and for each of us it’s a bit different, but we all share it. There’s a universal situation in which we’re all living. There are no unique traumas or stressors. For everyone, this is now ordinary life.

In some ways you kind of forget everything that’s going on. At the beginning of April, it was the anniversary of the end of the occupation of Bucha. I remembered it only when I saw that the streets were blocked off. Then I opened the news and saw that in addition to Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his wife, representatives of many European allies, and of the European Parliament, had come.

These visits were so important for the Ukrainian people. Allies came to bear witness to the fact that that these atrocities took place: that the occupation lasted 33 days and during that time 561 people were killed, twelve of them children; that about 100 or so people went missing; that the remains of many of the dead cannot even be identified because for 33 days they lay in the street, exposed to the sun and the wind and the snow.

You reflect on this, and think about the fact that you made it out of that hell alive, and you don’t just become scared. You become stronger.

This Easter, I went to visit my parents at their home in Zaporizhzhia. It was just as the truce was announced—the three days I was there were exactly the three days when there were no attacks, no bombings, and it was so nice. I just decided one day to go. Because Zaporizhzhia is a frontline city, many wives travel there to see their husbands, so it’s really hard to get transport. But I saw one ticket and I took the train east.

When I arrived, my brother opened a bottle of cognac he’d been saving for a special occasion and my mother started to cry. She thought he’d open it when he got engaged or something, but this ordinary visit—our being together—counted as a special occasion.

Even more than in Kyiv, the sense of loss in Zaporizhzhia was deepened by the nerve-racking situation. People are so used to living in a state of shelling and war that they can’t do without it anymore. It seems to me that there will be a shock, when, God willing, everything is over. People will feel uncomfortable without these explosions, without constant shelling. It’s been going on for three years—people have it in their subconscious that this is the way it should be.

For a time, many people were sharing the photo of President Trump and President Zelenskyy meeting at the Vatican. Everyone still believes so fervently that the horror will end, because it’s so painful. It’s not just people who live in fear of drones. The pain is the pain of mothers who lose their children, of warriors who lose their wives, their husbands. There is the constant shelling of frontline territories, where civilians who travel by car are killed every day. It’s the crazed grief of people who fled the territories that are now occupied, and left their parents behind. We hear of the horrors being committed by Russian soldiers in the occupied territories. I don’t even want to describe it.

The Ukrainian people strongly believe that when negotiations begin something good will happen to put an end to this war, which was unleashed not by Ukrainian citizens, but by Russian troops. God willing, something will work out.

Kateryna Kibarova is a Ukrainian economist and resident of Bucha.

Translated from the Russian by Julia Sushytska and Alisa Slaughter. This transcript has been edited for concision and clarity.

About the Translators: Julia Sushytska was born in L’viv and is a Visiting Assistant Professor in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture at Occidental College. Alisa Slaughter is Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Redlands. They recently co-edited and translated a selection of essays and lectures by Merab Mamardashvili, A Spy for an Unknown Country (ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart, 2020).

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Ukraine should have grown up more before seeking alignment with the UK and Nato. It is unfortunate that the ghosts of communism and all its paranoia and justified insecurities continues to infect countries like Russia, but Ukrainian leaders did this... they knew better than to poke the bear and yet they did it anyway. They did it for their own greed. They did it before Ukraine could stand on its own against Russian opposition. And now the Ukrainian people suffer for it.