Are you in or near London? Join me for a free community meet-up at The Perseverance, on Lamb’s Conduit Street, on Wednesday, June 4th, from 6pm! I’m excited to meet many of you there! — Yascha

I have at this point been taking part in public life for long enough that I usually have a sense of when I am about to say something controversial. If I make a strong criticism of Donald Trump or attack the excesses of wokeness, I know that I’m about to get some angry emails in my inbox. I no longer mind, really; it’s one of the less pleasant aspects of doing a job I truly love, one that is well worth the bad which comes with the good.

But from time to time, I still get a nasty surprise. For sometimes I blithely express a fact that I take to be far removed from the most emotive issues of the day and well-established in the relevant literature—only to learn from the state of my inbox that I had vastly underestimated the strength of popular sentiment about it.

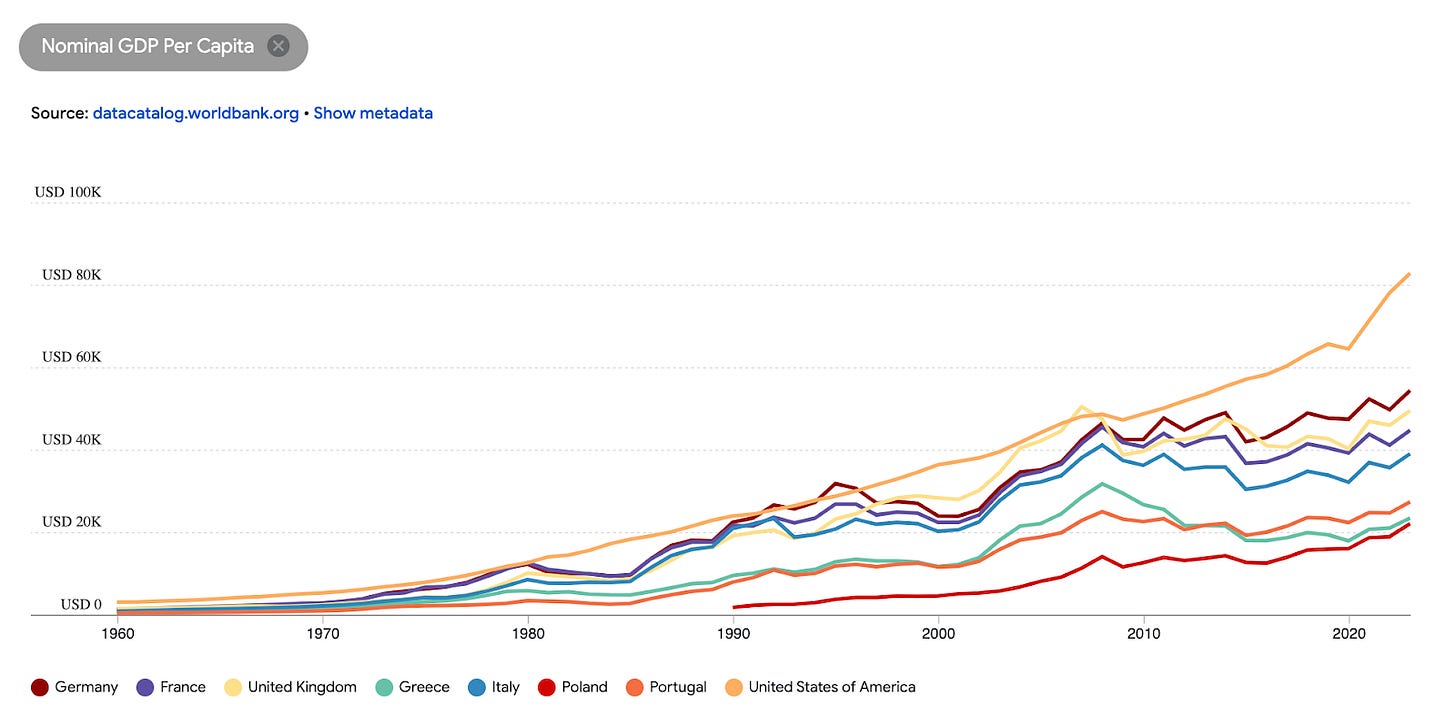

When I recently spoke to Paul Krugman on his interview show, for example, I casually mentioned the astonishing economic divergence between Europe and the United States. Whereas both continents were similarly affluent a few decades ago, America is now nearly twice as rich as Europe.

Cue a flood of outraged emails. Lots of people wrote to me to say that I must have the facts wrong, or at least must have failed to understand what really is important. Nominally, some correspondents conceded, the GDP of the United States might now be much higher than that of France or Germany. But that’s only because America lacks a welfare state and is so vastly unequal. In reality, the average European is doing just as well.

The strength of this reaction may have had something to do with Krugman’s audience, which skews progressive. But oddly, mentioning this fact has elicited a similar reaction from very different audiences in the past. When I off-handedly cited the same stat to a center-right Member of the European Parliament a few months ago, he too had an allergic reaction. Raising his voice, he insisted that such stats just weren’t meaningful; in all of the metrics of life quality that truly mattered, such as disposable income and access to good housing, Europeans were surely doing at least as well as Americans.

But that just isn’t true. Largely unnoticed by the general public on both sides of the Atlantic, America has pulled away from Europe. The average American is now vastly more affluent than the average European. And this difference in life quality is not only reflected in the overall size of the economy; it is also evident in much more practical metrics such as the disposable income, the living space, or the services accessible to the average person.

When I was a teenager, the United States and the richest large countries in Europe, such as Germany and the United Kingdom, were similarly affluent. In 1995, Germany’s nominal GDP per capita was a little higher ($32,000) than that of the United States ($29,000), with the United Kingdom lagging behind at a noticeable distance ($23,000)

When I was in graduate school, the United States and the richest countries in Europe remained similarly affluent. In 2007, on the cusp of the financial crisis, for example, Britain was in the lead ($50,000), with the United States ($48,000) and Germany ($42,000) following closely behind.

Since then, the two continents have markedly diverged. To an extent that few people have fully internalized, an economic gulf has opened up between America and Europe. On average, Americans are now nearly twice as rich as Europeans. According to the latest available data for GDP per capita, the United States stands at $83,000, with Germany at $54,000 and the United Kingdom at $50,000.

The contrast to less affluent European countries is even more striking. The GDPs per capita of France ($45,000) and Italy ($39,000) have fallen to about half of America’s level. Those of Portugal ($27,000), Greece ($23,000) and Poland ($22,000) are less than a third that of the United States.

GDP per capita is of course vulnerable to many of the critiques made by those who deny the existence of the great economic divergence. If America is vastly more unequal than Germany or the United Kingdom, then it is indeed possible that the lion’s share of that economic pie is captured by a very small number of people; in that case, America’s greater GDP simply wouldn’t translate into notably more affluence for the average person.

The problem with this seemingly plausible explanation is that it doesn’t hold up to empirical scrutiny. America is indeed somewhat more unequal than Europe. But the difference is not nearly as stark as some people on both sides of the Atlantic seem to assume. Indeed, America’s GINI coefficient, at 0.39, is only modestly higher than that of Britain, at 0.36, and only moderately higher than that of Germany, at 0.29. As a result, metrics that aren’t skewed by outsized wealth at the top, like household income at the median, still show a vast divergence between the two continents.

Take the official figures for median disposable income. These figures aren’t influenced by outliers at the top; colloquially, we might say that they represent a typical income. They also account both for the taxes that citizens pay and for the transfer payments they receive from the state; they thus reflect the fact that European countries tend to redistribute more between their citizens.1 Even so, the American lead remains clearly in evidence on this metric. According to the OECD, the median disposable income in 2023 was $51,000 in the United States, that in Germany $39,000, and that in the United Kingdom a strikingly low $33,000.

That’s a lot of numbers about income. And that makes it easy to imagine, as I think a lot of skeptics about the great divergence do, that they somehow don’t translate into things that are actually important for people’s everyday lives.

Sure, this argument goes, if you make a lot less money, you might find it hard to compete for certain goods whose prices are indexed to a global market. If your heart is set on a vintage Rolex or a supercar from Ferrari, much richer buyers from the United States or China might be able to price you out of the market. But when it comes to living in a nice apartment or going out to a delicious restaurant, the comparison between your wage and that of people in faraway countries matters much less; so perhaps Europeans are just as able to afford those crucial amenities.2

To test this hypothesis, I compiled a lot of data about day-to-day material amenities. How spacious are the houses and apartments of people on each side of the Atlantic? How often can they afford to eat out or to order takeout? And what kind of digital goods can they afford to access?

Let’s start with housing. Since home prices are very expensive in the United States, many American readers might imagine that Europeans can, despite their nominally lower incomes, afford to live in much nicer apartments. But the figures paint a different picture. The average home size in the United States is about 2,200 square feet. In Germany, it is 1,200 square feet. In the United Kingdom, it is 800 square feet. This extra space translates into all kinds of everyday amenities: Americans, for example, have about double the number of bathrooms per resident, enjoy much bigger refrigerators, and are much more likely than Europeans to have a dryer or a dishwasher in their home.

Dining out tells a similar story. The numbers are a little less exact, but estimates suggest that Americans eat out at a restaurant, have food delivered to their home, or order takeout about twice a week on average. According to a 2022 Gallup poll focusing exclusively on takeout food, for example, about 3 in 5 Americans say that they order food for pickup at least several times a month. Eating out is far less common in Europe, where there is a smaller number of restaurants per capita, and the percentage of income people are able to devote to eating out is significantly lower.

These differences in standard of living are even evident in many aspects of the digital economy. The United States and the United Kingdom both have about 80 personal computers for every hundred residents, making this one of the rare metrics on which Britain has kept up with its former colony. But Germany has only 66 computers for every hundred residents, with countries like Italy (37) and Poland (17) even further behind. The discrepancy is even more striking regarding the most basic currency of the digital age: access to the internet. According to Data Pandas, the median speed of a broadband connection in the United States is currently estimated at 280 Mbps. In Britain, it is 136 Mbps. In Germany, it is 96 Mbps.3

There’s more to life than being rich.

Europe is a beautiful continent. Most Europeans make a perfectly comfortable living. Many are deeply embedded in thick networks of community, which benefit from a high level of mutual trust. They live in vibrant cities with beautiful buildings and a strong sense of history. There is a reason why social media posts which highlight the appeal of a European lifestyle regularly go mega viral.

As someone who grew up in Europe, I myself feel the continent’s pull. I have happily lived in England in the past, love Paris, and fantasize at least once a week about permanently moving to Italy. Being rich isn’t the only important thing in life; indeed, to most people, including me, many other things are far more important.

It is also true that America’s economic model has very significant drawbacks. Average Americans are much better off than average Europeans; but thanks to a more generous welfare state and stronger community ties, the poorest Europeans probably get to lead a more dignified life than do the poorest Americans. And of course, there are unique annoyances and indignities that even comparatively affluent Americans suffer. For the most part, for example, I receive much better medical care in the United States than I ever have in Europe—but every time I have to deal with my insurance company, I wonder whether the increase in quality is worth the stress.

Americans have some good reasons to keep indulging their fantasies of living Under the Tuscan Sun or following in the footsteps of Emily in Paris. And Europeans can rightfully remain proud of the many things that make their continent unique and beautiful. Personally, I would much rather live in Berlin or Lisbon or Siena than in the typical American suburb.

But for those who are so inclined, it is possible to maintain this preference without denying the reality that Europe has suffered significant economic decline relative to the United States, and that this is now having serious consequences for the lives of ordinary people. Indeed, it is striking that my American friends who dream of moving to Europe usually do so because they can tele-work for U.S. companies or are about to retire; my European friends who dream of moving to the United States do so because they are frustrated by a lack of economic opportunities and fear that they won’t ever find an adequate outlet for their talents.

When a development as striking as the economic divergence between Europe and America is so little known or discussed by the broader public, the reason is usually that it discomfits the narrative of all kinds of different constituencies. That is clearly true in this case: Europeans and Americans, the left and the right, each have reasons of their own to ignore or downplay this fact.

Europeans don’t like to recognize how far they have fallen behind the global economic leader. Meanwhile, Americans on all sides of the political spectrum have become so consumed with the negativity bias of social media that they don’t want to admit that there might be any good news about their own country.

This refusal to face the facts is now a bipartisan phenomenon. The American left, for example, is singularly focused on the inadequacies of the welfare state and the legacy of “structural racism.” To point out that, wealth inequality and the disparity between different ethnic groups notwithstanding, the average African-American is now much richer than the average European would seem like sacrilege to many progressives.4

Meanwhile, big parts of the American right have become convinced that the global system built by the United States has turned to its disadvantage. They see the country, as Trump did in his first inaugural address, as the land of American carnage, with “mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities [and] rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.”

But for all of America’s problems, what’s truly striking about the last decades is just how successful the United States has been. As China rose, Europe’s share of global GDP cratered; America’s share held up astonishingly well. As a result, two regions that had until quite recently been similarly affluent have undergone a remarkable divergence. Gradually but seemingly inexorably, America has become vastly richer than Europe.

A version of this article was originally published at The Dispatch.

One reason why differences in median disposable income on both sides of the Atlantic more closely mirror GDP per capita than some might expect lies in how tax systems are structured. While top marginal tax rates are often somewhat higher in Europe, many European countries impose significant taxes starting at relatively low income levels, and heavily rely on regressive sales taxes. By contrast, the United States has lower sales taxes and levies comparatively modest taxes on low-income earners while taxing high earners at rates that are broadly comparable to those in Europe. As a result, the U.S. tax system is, by most metrics, actually more progressive than its European counterparts.

Most of the figures I have shown so far already try to correct for this mechanism; absolute differences in income, for example, are much larger than the ones I have presented, which were expressed in purchasing power parity-adjusted dollars.

In fairness, some European countries do better on this metric. France slightly beat the United States, with median speeds of 291 Mbps. Spain also did relatively well, with median speeds of 248 Mbps.

According to Pew, the median income for black U.S. households was $54,000 in 2023. According to Eurostat, the median income for all EU households was about $23,000 (€20,416) in 2023. Even the incomes of average households in the richest EU countries, such as Germany at $29,000 (€26,274) and Denmark at $38,000 (€33,900), was markedly lower than that of black U.S. households. Out of 27 EU countries, only the average household in Luxembourg enjoys similar income to that of the typical African-American household. (These figures may moderately overstate the extent of the difference in median household incomes since European figures are adjusted for household size and composition, whereas the U.S. figure is for unadjusted household income.)

The deindustrialization of Europe has been concerning and yet fascinating to watch from the US. As an oil and gas engineer I often see the world through the lens of energy production and consumption. I had a LLM conversation about your article and my concern about the unaddressed energy policy issues. The conversation was condensed down to this :

**Comment for Yascha Mounk (100 words)**

Your nuanced institutional analyses might benefit from examining Europe's self-inflicted energy crisis as a case study in governance failure. Post-2008, Europe made three fateful decisions: prematurely closing reliable nuclear plants, banning domestic shale development, and deepening dependence on Russian gas—while heavily subsidizing intermittent renewables. Meanwhile, America embraced shale innovation. The consequences? Beyond electricity costs, Europe's industrial gas prices soared 345% above America's, devastating competitiveness. This policy-driven vulnerability culminated with Putin weaponizing energy supplies in 2022. Few factors better illustrate how technocratic hubris in resource policy can undermine democratic capitalism's foundational economic security and geopolitical independence.

The big beautiful bill has not delivered the fruits of inequality yet to the actual American in all parts of the country. The Medicaid cuts alone will make America reverse its unequal treatment of people by income.