The Separation of Powers Is (Almost) Dead

Congress is no longer a safeguard of American democracy.

This article is part of an ongoing project by American Purpose at Persuasion on “The ‘Deep State’ and Its Discontents.” The series aims to analyze the modern administrative state and critique the political right’s radical attempts to dismantle it.

To receive future installments into your inbox—plus more great pieces by American Purpose and Francis Fukuyama’s blog—simply click on “Email preferences” below and make sure you toggle on the buttons for “American Purpose” and “Frankly Fukuyama.”

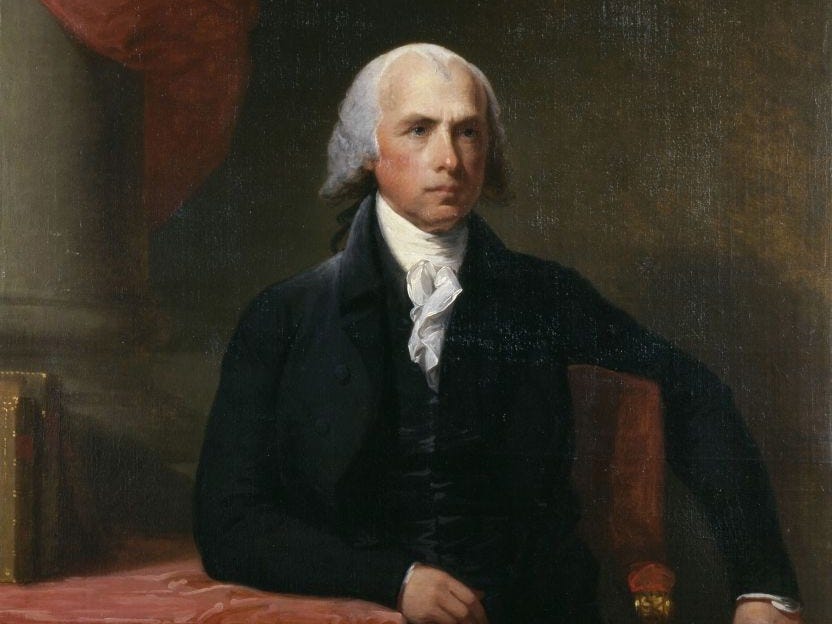

Not long ago, a friend looked at what was happening in Washington and said, “James Madison must be turning over in his grave.” I checked the U.S. Geological Survey’s earthquake tracker and, sure enough, its map showed a cluster of quakes right around his grave in Montpelier, Virginia.

The cause: the separation of powers system that he inserted into the Constitution is—almost—dead. Congress has lost its constitutional role to shape and constrain executive power. That’s been underway for years, but the Trump administration has cemented it.

The shift is so deep and profound that it will be very, very hard to get the Constitution back to the balance that Madison designed.

First, Trump buried the government under an unprecedented blizzard of executive orders. Since Ronald Reagan, the average annual number of executive orders has ranged between 35 (for Obama) and 55 for Trump (in his first term). Biden wasn’t far behind with 41.

Trump has already hit 218 for his first year (as of early December). Negotiating with Congress is inconvenient for presidents, and all of them like to legislate through executive action, but Trump has made it a central part of his strategy.

Second, Trump has treated congressional appropriations as mere suggestions. In under a year, he has already accounted for 40% of all rescissions in the last 50 years. In addition, the Government Accountability Office has found that the administration violated the law in impounding funds more than half a dozen times, for everything from electric vehicle charging and Head Start to medical research and FEMA funds, with impoundments totaling more than $400 billion.

The administration’s position flows from the unitary executive model: Congress might appropriate money, but the president can decide whether to spend it. Congress’s “power of the purse,” Madison wrote in Federalist 58, “may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people.” Unless, that is, the president grabs away the power of the purse. Upsetting that balance, Hamilton argued a bit later, “would destroy that division of powers, on which political liberty is founded; and would furnish one body with all the means of tyranny.” Hamilton was the strongest advocate of executive power among the founders, but he never would have countenanced going this far.

Third, Team Trump has wiped out major functions of government by kicking away their administrative support. Only Congress can eliminate agencies and the functions they administer, but the administration has effectively wiped out foreign aid by firing virtually everyone working for the U.S. Agency for International Development.

He’s weakened education programs by parceling out functions of six Department of Education offices to four different agencies. As part of the plan, the administration is busting up congressional oversight. Indian Education programs are moving to the Interior Department and international education programs are going to the State Department. Major grant programs for elementary, secondary, and postsecondary education are being sent to the Labor Department. The first two moves would uproot programs from the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Subcommittee. The last one would remove the oversight that members of Congress are used to. It’s a two-fer: making good on his promise to (almost) kill the Department of Education, and weakening Congress while he’s at it.

Fourth, Congress isn’t getting any help from the Supreme Court, which has so far winked at the administration’s steps. Most analysts reading the Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo have—correctly—seen it as overruling its previous holding in Chevron U.S.A Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., which ruled that executive branch experts deserved deference in interpreting the law. The remedy: Congress could legislate in more detail to limit administrators. But it’s unrealistic to expect Congress to do this. In that case, the Court held, the courts would supply the interpretation. So in a bold stroke, Loper Bright weakens Congress even more than the executive branch.

Then, in the oral arguments over Trump v. Kelly, the Court seemed poised to increase executive power even further by overruling the 90-year-old precedent in Humphrey’s Executor, which held that the president could not dismiss the heads of independent regulatory commissions. Lost in the scuffles over the case is an important undercurrent: Congress created these independent regulatory commissions and insulated the commissioners from removal only for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” If the Court upends Humphrey’s, as expected, it would also radically trim the ability to define the role and power of administrative agencies.

From there, it would be a very short step for the Court to rule that the president can fire any executive branch employee. That would torpedo the fundamental principles of the merit system that Congress established in the Pendleton Act in 1883 and has continuously reinforced for more than 140 years since. Little would then be left of Congress’s balance of power with the executive branch, if the president can dismiss those in charge of implementing the laws Congress passes, gut the agencies in charge of implementing them, and refuse to spend money for congressionally authorized programs, for good measure.

Finally, Congress is at a strategic disadvantage in reining in the executive branch. The founders deliberately created Congress as a “cool and deliberate” branch, as Federalist 63 puts it. Conservatives point to the wisdom of a “deliberative republic,” captured in Congress.

But that is anything but what is happening. Steve Bannon famously talked about the need to “flood the zone with s***.” The more the Trump administration floods the zone, the more disoriented Congress becomes. It was never meant to move fast, and flooding the zone has meant Congress has become even more unable to move at all.

It would be tempting to suggest that a different president, a different Congress, and a different Supreme Court might be able to unravel all this. Team Trump, however, is moving so fast that it intends to make that impossible. And even if a different president tried to do so, it would inevitably begin by reversing Trump’s executive orders using more executive orders, which would continue to relegate Congress to the back bench.

Congress could choose to rise up, but that would require Congress to do what it has been increasingly unable to do. Since 1997, it’s been unable to pass a budget on time—and since 1998, it has only twice managed to pass a continuing resolution that covered more than half the fiscal year.

The founders created Congress as the “people’s house,” and labored far more over Article I of the Constitution than over the president’s powers in Article II. That’s because they thought that the ultimate safeguard against presidential overreach was a robust Congress. They guessed wrong.

The sad conclusion is that Trump’s speed and skill, matched by Congress’s torpor, has virtually killed the separation of powers. Be on the watch for more tremors around Montpelier.

Donald F. Kettl is Professor Emeritus and Former Dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Policy. He is the author, with William D. Eggers, of Bridgebuilders: How Government Can Transcend Boundaries to Solve Big Problems.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Trump has done a number on our Democratic institutions. The question is who is really going to defend Democracy and how are they going to do it. Clearly, Trump has done his best to see that Congress has lost much of its constitutional role, radically accelerating a trend that has been happening since the New Deal. The Supreme Court is watching its back knowing Trump would have no hesitation to go through with packing the court if needed. Many liberals intended the independent agencies in the post New Deal World to serve as a fourth branch government, professionalizing complex decision making. This branch of government was never really fully envisioned by the Constitution (outside rudimentary Cabinet officer powers). The courts (perhaps to a certain degree rightly) and Trump (nefariously) has trimmed their power.

My question is what now? Does the problem really get solved by changing the players? Or will a different party and/or person merely step into the Presidency and assume 90% of the power that Trump has accrued to the Presidency? Trumps actions make me concerned about Democracy in America. The fact that conservatives, liberals and progressives in government and academia have not proposed anything in the way of constitutional or legal reforms to curb the power of an Imperial Presidency worries me even more. I am concerned that for the majority of the political players and people in this country, the lack of attention and discussion masks a belief that an all powerful Presidency is fine as long as the “right” person is in power.

The 17th Amendment bound the Senate to democracy’s central flaw: the passions of the crowd. What was once a deliberative body has become a stage for mobocracy, and Congress now resembles a bar fight. For decades the mob has shouted “give us more,” and the leaders who rise from that din are those most willing to indulge it. The result is a nation driven toward bankruptcy, fiscally and morally.

Many I know did not vote FOR Trump, but out of exhaustion with the Democratic mob. They saw in him a blunt instrument to shatter the entrenched bureaucracy. He is a bully, yes—but in breaking things apart he has revealed just how deeply Washington is steeped in liberal, socialist, and statist bias. From the outside, it is almost entertaining to watch something like a fair fight unfold. Yet the long-term picture is darker: democracy cannot endure until its fatal flaw is addressed.

The remedy lies in restoring the original design. If state legislatures once again appointed Senators from among their elected ranks, Congress would regain order and comity. Washington would recover the separation of powers as intended, and the republic would be anchored once more in stability rather than the shifting passions of the crowd and rebel rousing politicians.