Something has gone badly wrong with the American university.

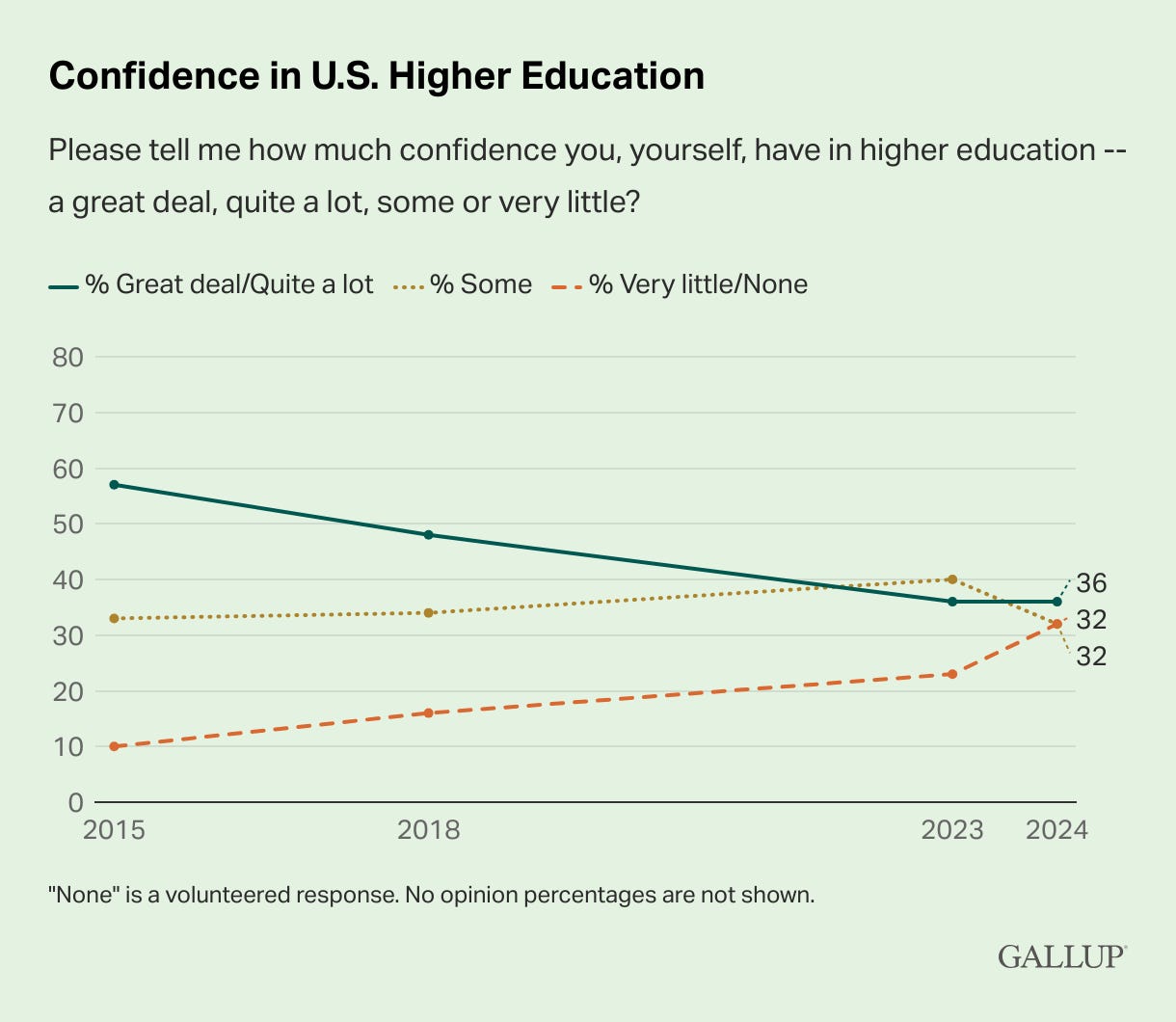

As recently as a decade ago, a big bipartisan majority of Americans said that they have a lot of trust in higher education. Now, the number is down to about one in three.

The decline in public support for universities has many causes. It is rooted in the widespread perception that they have become ideological monoliths, barely tolerating the expression of any conservative opinions on campus. It has to do with the rapidly growing endowments of the largest universities, which now command a degree of tax-exempt wealth that seems to many people out of all proportion to their pedagogical mission. It has to do with their admissions policies, which judge prospective students on the color of their skin and the degree of their disadvantage, seemingly in defiance of a recent Supreme Court order. And it has to do with the rapidly rising costs of university, with the annual price of attendance now approaching six figures at many selective schools.

The decline in public support for higher education has also had severe consequences. Donald Trump and his allies have clearly identified universities as a significant bastion of left-wing political power, and seem determined to weaken them by any means possible. The resulting assault on top institutions from Columbia to Harvard is deeply illiberal. Whatever the faults of the universities, it obviously chills speech and undermines academic freedom when the federal government tries to exact revenge by doing what it can to weaken the sector. But what’s striking about the Trump administration’s attack on American higher education is not just how brutal and illiberal it is; it’s also how little most Americans seem to care.

Anybody who wants American universities to thrive—as I do—therefore needs to walk and chew gum at the same time. Institutions like Harvard are right to resist attempts to erode their academic freedom by imposing the substantive views of the Trump administration on them. It is therefore good news that a district court judge ruled yesterday that the manner in which the administration canceled federal funding for Harvard violated the university’s First Amendment rights. But rightful resistance to an illiberal president must not serve as an excuse to keep ignoring the genuine problems which have led to such deep popular revulsion for the entire sector.

A few voices within academia are starting to recognize that. It is, for example, smart that Yale University has instituted a new committee that is tasked with investigating the roots of the university’s fall from public grace, and to investigate possible remedies. But given that such committees usually struggle to go beyond the smallest common denominator, and that this particular committee is exclusively composed of faculty members at the university who by definition have a large stake in preserving the status quo, I am not holding my breath for its findings.

To change the massive shift in public perception of academia, it would, it seems to me, be necessary to take radical steps to change its current nature. And so I want to make a modest proposal for how universities can refocus on their core mission of teaching and research—and become both much more affordable, and much more deeply embedded in the fabric of American society, in the process.

One of the strangest things about an American university education is that it bundles a whole lot of different things together. If you want to take a course in high-level mathematics or listen to the lectures of an accomplished historian of Ming China, you must also buy membership in one of the country’s most lavish gyms; purchase all-you-can-eat meals at breakfast, lunch, and dinner; rent a room in a student dorm even if your parents happen to live a few miles down the road; pay an army of administrators whose jobs range from organizing parties to hiring puppies for you to pet during finals; subsidize student clubs that are devoted to such varied activities as playing Dungeons & Dragons or blind-tasting exclusive wines; and help to pay the lavish salaries of football and waterpolo coaches.

This is a financial problem. Attracting top-flight professors and investing in cutting-edge research would be expensive even in the absence of all of these frills. But one reason why tuition has skyrocketed at leading institutions is that they have turned themselves into four-year luxury vacations that offer a breadth of services with which not even the lavish resorts featured in the White Lotus could compete. If students could attend Harvard or Rice without having to purchase the world’s most exclusive and extended all-in-vacation package, it would be much more affordable to attend these institutions.

Bundling also helps to turn universities into tightly sealed bubbles at odds with the communities in which they are located. The vast majority of students at top institutions barely interact with the community around them. They don’t have local landlords or neighbors, don’t have locals for roommates, don’t run into locals at the gym, and barely patronize local establishments. The fact that they barely leave campus or interact with somebody outside the university community is a major reason why many campuses have turned into such monochrome hot-house environments.

Bundling is also at the core of the crisis of ideological conformity on campus. Many conservative critics suspect professors of using the classroom to propagandize their views; while that is certainly true for some faculty members, it simply does not describe the behavior of most professors. Faculty members, in turn, like to complain that the true culprits are administrators, who are indeed more likely to be evaluated for the degree of their ideological conformity with the basic tenets of DEI and CRT; but even an army of administrators would struggle to impose ideological conformity on students who were embedded in ordinary communities. Indeed, a lot of the ideological conformity at American universities is simply grounded in the all-encompassing nature of the campus experience: It is vastly harder to disagree with other people in your discussion section if your classmates are also your roommates and your gym buddies and your teammates and your fellow worshippers and your only friends in a hundred mile radius.

Many American readers will probably assume that it is natural for all of these things to go together. But America is in fact highly anomalous in this regard. In most countries in Europe, Asia, and South America, universities are much more closely associated with their core academic functions. When students play sports, they usually do so as a part of private clubs. When they need a place to stay, they rent normal apartments in normal neighborhoods. And when they go to pray, they do so in a local house of worship.

The immersive campus experience characteristic of elite American institutions admittedly has real advantages. As I know from my own undergraduate experience at a campus university in the UK, there is something special about spending one’s formative years surrounded by smart and ambitious young people. If they are given the choice, many college students will, despite its steep cost, still choose to opt into that experience.

But societies in which the undergraduate experience looks very different also turn out to have big advantages. In these countries, a much greater share of students goes to university close to home, making it much easier for them to stay friends with high school buddies or to form new friendships with members of the local community who are not on a similar trajectory towards wealth and power. As a result, the governing elites of these countries tend to be much more rooted in ordinary communities and much more knowledgeable about the lives of people outside the small elite bubble that has come to dominate American life.

And of course, the material savings also matter greatly. Young people in these societies can access an excellent education without going into huge debt. Graduates from top universities abroad are much less constrained in their career choices, making it possible for them to go into public service or to take entrepreneurial risks like founding a start-up; in the United States, by contrast, a disproportionate share of the brightest minds educated at great cost in the Ivy League goes straight off to Goldman or McKinsey.

Here is how unbundling the American university would work.

When students are accepted to any university, they would henceforth have a choice between (at least) two prices. The first price—let’s call it the White Lotus option—would offer the bundled service which they currently need to purchase in order to enroll. On top of access to their academic coursework, it would provide them with a room in a dorm, with a meal plan, with access to the university gym, and with all of the other amenities to which college students have become accustomed.

The second price—let’s call it the I’m Here to Learn option—would be based solely on the cost of providing a stellar education. It would allow students to complete their undergraduate education, including access to lectures and seminars and laboratories, but exclude the other amenities which have come to be such a big part of the university experience. Students would themselves be responsible for securing housing, for feeding themselves, and for figuring out their leisure activities.1

Are colleges, as nearly all of them claim, actually serious about making their institutions “financially accessible,” about catering to a “diverse set of needs,” and about creating greater “ideological diversity”? Well, here’s the logical first step towards realizing all of these goals.

To be sure, most colleges are very unlikely to heed my advice. Allowing people to opt out of the White Lotus option would likely lead to a reduction in income for universities. It might force them to abandon ongoing plans for ever-more lavish campus buildings. And it may even negatively affect their standing in the influential rankings compiled by U.S. World and News Report.

But if universities refuse to unbundle themselves, the government could easily step in. If the federal government makes funding for neuroscience or cancer research depend on ensuring that faculty members don’t say (supposedly) offensive things, it is violating the First Amendment, and its implicit prohibition on viewpoint discrimination. But courts have long recognized the government’s ability to make federal funding conditional on a broad set of conditions as long as these don’t discriminate against particular viewpoints, and past administrations have already used that power to shape how universities behave in highly intrusive ways. So, unlike the current attacks from the Trump administration, which violate longstanding principles of free speech, such a rule would be perfectly compatible with the First Amendment. To tell a university like Columbia that it needs to put a particular department into academic receivership or to command a university like Harvard to survey the ideological leanings of key staff members violates viewpoint neutrality; to tell both that the federal government will stop subsidizing institutions that compel a student who simply wants to learn to cross-subsidize the school’s water polo team or its puppy social hour does not.

As I have feared since (before) the day Trump got reelected, many of those who are deeply worried about his administration are responding by digging in their heels. Instead of recognizing that mainstream institutions, from media outlets to public health authorities, have made genuine mistakes that made them lose the trust of many ordinary Americans, they are insisting that they have all along been right about everything. This kind of denialism simply isn’t going to work. If they want to regain public support, America’s leading institutions must persuade the public that they are capable of learning from their mistakes—and take action to fix them.

This is especially true for academia. Over the last decades, universities have increasingly strayed from their mission of teaching students and advancing research. If they are to regain the public’s trust, they must find bold and innovative ways to refocus on their core societal purpose. Allowing students to access a world-class education without having to book a four-year holiday in a world-class luxury resort is the right first step on that long journey.

Any big change like this has both advantages and disadvantages. One disadvantage of this option is that richer students may be more likely to choose the White Lotus option, making differences of financial status more visible on campus. But while this is a genuine disadvantage of this scheme, I do not think it is dispositive. First, differences of wealth and status are already very salient to most undergraduates at elite schools; the pretense that everyone’s access to the same meal plan makes these differences invisible is an unconvincing form of make-believe. And second, it seems rather strange to force less affluent students—but not the rich students whose parents or grandparents can easily foot the bill for all those extra amenities—into decades of debt so that everyone can pretend for a few years that these vast real-world differences don’t exist.

As an Australian, a lot of these features of the US college experience are - each on their own - familiar from countless films and TV shows. But to read about them all as a non-optional package deal is eye-opening. For the vast majority of Australian students, going to university is the 'I am here to learn' option, attending a university in their home city, and either sharehousing or staying at home with their parents. There is no semi-professional college sport industry to speak of, and fraternity and sorority houses are non-existent. One possible benefit of the US culture, however, might be a stronger post-COVID return to in-person lectures and seminars and a more thriving on-campus culture. In Australia, the option for asynchronous, online education has had some impact on attendance, with some universities actively reducing face-to-face teaching.

This is a great point, especially about "unbundling" all the fees and accessories (including requirements that students live in expensive dorms). Too often, those are just used to fund more staff positions or activism by certain organizations. Students should have a right to refuse those and focus solely on their education. Very often though the people advocating for these higher fees are the activist students who benefit from them as well as the staffers whose salaries are funded in part by them.

That said, many students are beginning to rightly suspect that extracurriculars play a larger role than many of their classes in helping their resume and gaining career-applicable experience. So it's important that those be offered, but in a reasonable way.

There's also a lot of financial incentives for universities to offer that "White Lotus" style as more full-pay students can, they argue, help subsidize lower-income students on financial aid. I'm not sure how the math breaks down on that in practice though.

Finally, one other idea: encourage more 3-year degree tracks, especially through the use of summer courses or the ability for students to knock out certain required classes online.