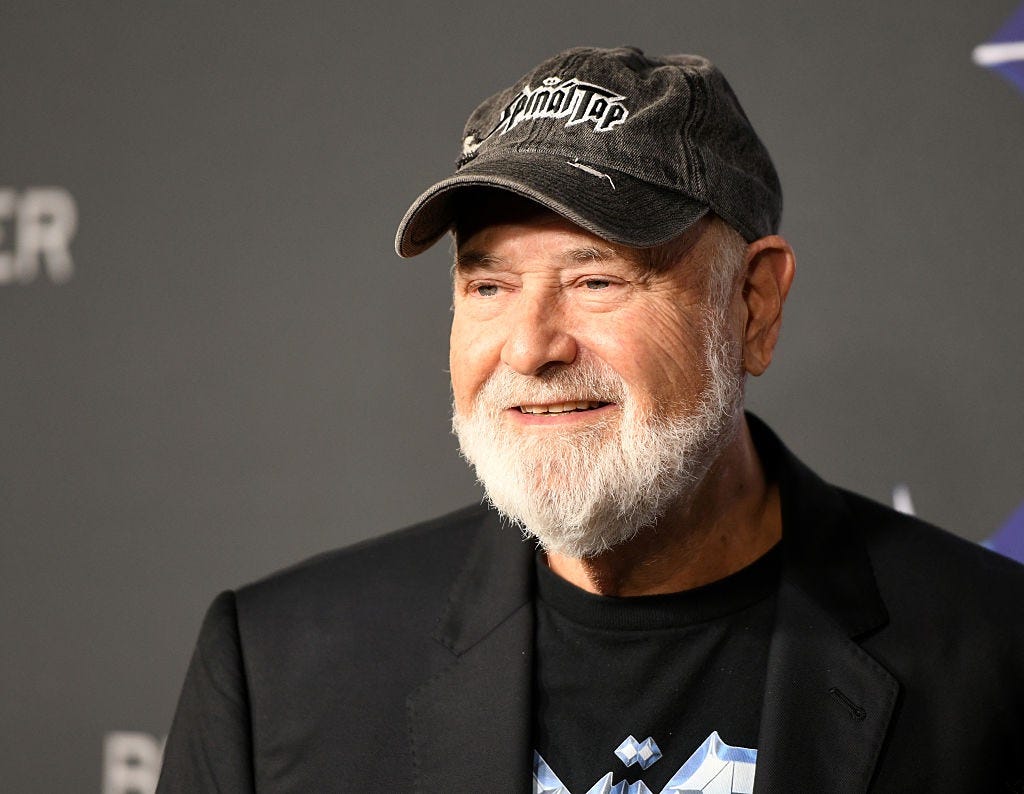

What Rob Reiner Was Telling Us

Whimsy, humor, a high-trust society. With the news of the past days, it all feels so distant.

A few hours ago, in a very lighthearted way, I was putting out a questionnaire to a Gen Zer in an attempt to test “intergenerational understanding” for an article I was writing, and one of the phrases I instinctively sent out was from The Princess Bride: “Life is pain, highness, anybody who says differently is selling something.”

I was in a nice mood and didn’t feel like checking the news or the WhatsApp messages that were starting to pile up, and when I finally did they were about the murder of Rob Reiner and his wife Michele, and whether this publication could work up any response to it.

The cognitive disconnect for something like this is total. Rob Reiner, for several generations of Americans, occupies a uniquely happy place in their imagination. This Is Spinal Tap was named the funniest movie of all time in a Time Out survey. When Harry Met Sally defined the romantic comedy and, for about a decade, changed the way everybody ate turkey sandwiches and thought about the New Year’s song. And The Princess Bride was in a special category entirely of its own—when an ESPN analyst suddenly began doing an entire football game recap in Princess Bride references, he found that his fellow analysts had no trouble at all keeping up. When I wanted to check whether the young were still basically alright, it was a Princess Bride quote that first came to me.

So hearing that Rob Reiner and his wife Michele were murdered inside their home, allegedly by their son, is the sort of thing that just doesn’t compute—it’s like hearing that Mr Rogers was brutally killed or Bert and Ernie met a violent death. This was not, it seems, an ideological or political crime; but fighting for headline space with the shooting at Brown University and the shooting at Bondi Beach, it’s very hard to shake the impulse to get a little zeitgeisty, and to feel that something or other that was promised about the way the world worked has been decisively, irrevocably ruptured.

Reiner’s movies were almost unimaginable except set against a backdrop of ease and plenty. The stakes tended always to be ludicrously low—the crisis in The Princess Bride is the kid in the Bears jersey not wanting to have his grandfather read to him, while in This Is Spinal Tap, it’s being out of proportion with one’s stage props; the peak of emotion in When Harry Met Sally is that a young woman is concerned that she’s “going to be 40 someday.”

It’s incredible how far away that whole world feels right now.

Reiner’s life coincided with a golden age in American history—he was born in 1947 to one of the leading show business families in the United States. His great run of films stretching from 1984’s This Is Spinal Tap to 1995’s The American President overlapped with a period of unprecedented prosperity and the fall of the Soviet Union. A particular sensibility came with that—a limitless optimism, which wasn’t exactly naive, but had a worldview built into it according to which, no matter what, you keep moving forward and eventually things do work out in the end.

That sensibility comes through very strongly in the interviews and public statements Reiner made about his son Nick’s addictions. Nick had very openly struggled with drugs and psychological issues—according to a People Magazine article in 2016, he had first gone to rehab around his 15th birthday, had been through 17 rehab stays by the time he was 22, and had had stints of homelessness.

Reiner, at least in public, very clearly believed in the light at the end of the tunnel. In an interview with The Los Angeles Times in 2015, Reiner indicated that he regretted the “tough love” approach he had been encouraged to adopt and wished he had simply been softer with Nick. “We were desperate and because the people had diplomas on their wall, we listened to them when we should have been listening to our son,” Reiner said. And there was the evident hope as well that art would be redemptive. “Our relationship had gotten so much closer,” Reiner said of working on the 2016 film Being Charlie, which Reiner directed and Nick co-wrote and which was closely based on Nick’s difficulties with addiction.

At the time of Reiner’s death, his murder is in competition with a trifecta of terrible news stories—the Bondi Beach shooting in which at least 15 people were killed by gunmen while celebrating Hanukkah and the shooting at Brown University in which two people were killed. The very clear sense is of having entered into dark times—the kind of story where it’s not clear that optimism will prevail or that there will in fact be a happy ending. A year after Franklin Foer in an Atlantic article declared, “The golden age of American Jews is ending,” anti-Semitic violence has become commonplace. Mass shootings and school shootings are so frequent that what is produced is a society of distrust—it turns out, for instance, that two of the survivors of the Brown shooting had survived other school shootings.

There is a great deal of intellectual effort at the moment to try to understand what went wrong, how we got from the idyll that backdropped When Harry Met Sally and The Princess Bride to the fraying social fabric that we have right now—the deindustrialization and hollowing-out of the heartland, the inability to pass meaningful gun control legislation, the hyper-partisanship in Washington, the internet and the deracination it brings all come in for consideration, but there is no clear answer and probably there never will be. The greatest casualty of it in some sense is the worldview that somebody like Rob Reiner seemed to embody—the good-humored, endlessly humane belief that, somehow or other, things would work out. What we’re dealing with at the moment is the recognition that it’s possible they may not.

Sam Kahn is associate editor at Persuasion and writes the Substack Castalia.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

The stakes were hardly low in A Few Good Men, or Misery, or Stand by Me. For that matter, he first became a public figure making humor out of a deeply divided America; even before All in the Family he was a writer on the Smothers Brothers.

I'm not sure what my point is, except that what he contributed to this culture was something good.

Perhaps, if we want a high-trust society, we might try not doing wholesale demographic replacement.