One thing I discovered, when I was working in New Hampshire on a campaign in 2008, is that people there have long memories. I was fresh out of college and thought everybody would be as excited as I was about Obama. But far more often than I would have expected, the conversation turned to… Jimmy Carter. In particular, what rankled was Teddy Kennedy’s primary challenge to Carter in 1980. “That tore us apart,” I remember one veteran operative telling me. At least within the collective consciousness of Democratic New Hampshire, the primary was held responsible for Carter’s humiliating loss to Ronald Reagan.

Fear of a divisive primary clearly ran very deep within the Democratic establishment. What seemed to have been forgotten, however, was the somewhat thornier reality. Carter was struggling before Kennedy’s challenge: his approval rating dipped as low as 28% during 1979. Likely, anyone whom the Democrats nominated would have lost to Reagan. In that situation, there was much to gain and little to lose from a contested primary; the Democrats’ misfortune was not that Teddy Kennedy ran but that Chappaquiddick and a rambling performance in a television interview made him a weaker candidate than expected, leaving Democrats without a strong alternative to Carter.

The Democrats face an analogous situation heading into the 2024 election. The conventional wisdom—which seems to have been internalized by potential challengers to Joe Biden—is that a contested primary would disastrously weaken the party in advance of the general election. But I’m not so convinced. Biden’s current approval rating is 37%. For reference, the average for a sitting president at this stage of a first term is 53%. A new poll shows Biden trailing Trump by six points, and DeSantis by five, in hypothetical head-to-head matchups. And Democratic voters, while approving of Biden’s performance as president, also express an unmistakable desire for anybody else to be the nominee, with 58% opting for an alternative in a recent poll.

The uncomfortable reality is that incumbency doesn’t necessarily confer an advantage heading into the upcoming election. Given concerns about his age, and his poor polling, Biden would make a less-than-inspiring candidate. And elections have changed so dramatically in the era of social media and around-the-clock news coverage that the conventional wisdom about the benefits of a quiet primary may no longer apply.

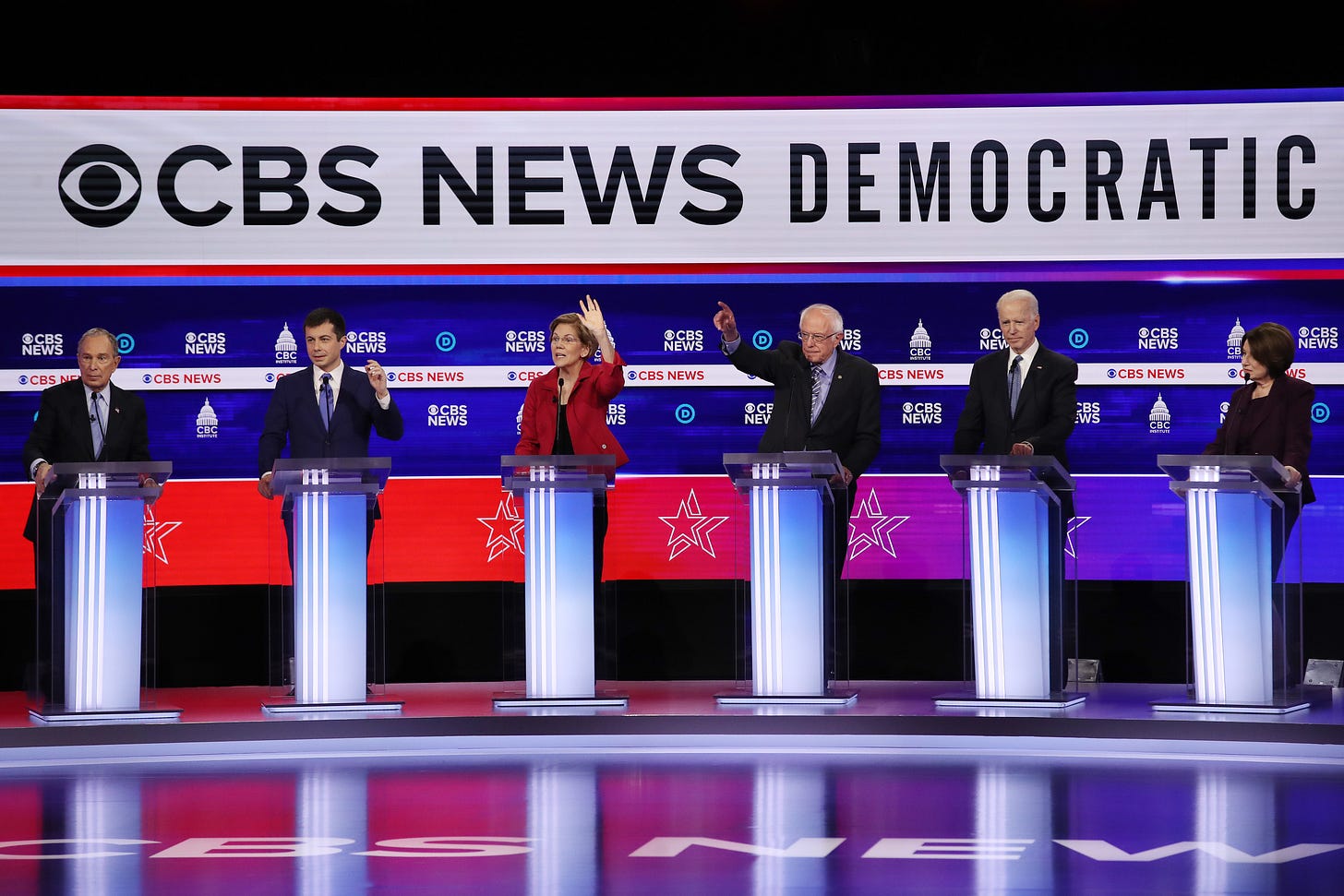

At the moment, Democratic mainstream figures, many of whom seemed to have been preparing for a challenge since at least the summer of 2022, have closed ranks behind their presumptive nominee. California Governor Gavin Newsom, who had aired ads in battleground states far from California, beat a hasty retreat after the Democrats’ better-than-expected performance in the midterms, telling Biden, in a conversation overheard by a reporter, “I’m all in, put me in coach: we have your back.” None of the other expected challenges (from Pete Buttigieg, Cory Booker, Bernie Sanders, etc.) have materialized.

But even as the Democratic establishment congratulates itself on a feat of party unity, this clearing-of-Biden’s-path may well be remembered as a critical strategic blunder.

One standard argument against a contested primary is that it would be divisive, leading to a turn to the party’s left—a rift that could be exploited by Trump in a general election. But that strikes me as a less-pressing worry. The last few contested Democratic primaries have been models of civic discourse—with a variety of competing visions for the party talked through, with moderates ultimately prevailing, and with the party presenting a united front by the time of the convention. The more salient concern is that the vacuum of an “empty” primary field creates an opportunity for the fringe to issue a concerted challenge and to pull the political discourse in a very different direction.

Already, it’s apparent that the absence of a mainstream challenger does not make for a quiet primary. Bobby Kennedy Jr. and Marianne Williamson have declared their candidacies. In the past, the Democratic establishment would tend to just ignore fringe voices, but, now, it may not be so simple. The analogy here would be to 2016, when the “good Dems” got out of Hillary Clinton’s way but, in so doing, opened an avenue for Bernie Sanders and his (at the time) fringe democratic socialist positions to gain a public hearing in a way that they never had before. Kennedy is currently polling as high as 21%. With no other candidates to cover, media outlets will find themselves compelled to give attention to Kennedy’s talking points—to things like vaccines, internet censorship, the merits of Biden’s Covid response. And even if legacy media stonewalls Kennedy, his arguments will circulate on social media.

Meanwhile, with no mainstream candidates challenging Biden, that means, essentially, a year in which the Democratic establishment does nothing to “feed the beast” of the news cycle—and a year in which mainstream Democratic positions go unheard. In the past, that might have served the interests of unity and of a show of strength; the more likely outcome now is that the Democratic mainstream loses an opportunity to shape the narrative.

I’ve been haunted ever since I read it by Donald Trump’s calling-of-the-shot in 2013. To a group of GOP operatives, he said presciently, “I’m going to suck all the oxygen out of the room. I know how to work the media in a way that they will never take the lights off of me.” What Trump fundamentally understood—a lesson that I worry still has not been fully absorbed by the political mainstream—is that, in the current news era, attention matters far more than credibility. Rather than carefully burnishing an image, much of the ticket to winning is simply about being constantly in the minds of voters—allowing voters to grow so familiar with a candidate that they can’t help but (often in spite of themselves) become somehow fond of them.

In the Democrats’ surge of party unity, there’s a somewhat atavistic desire to return to the way politics used to be. Biden is our president, seems to be the internal monologue, and, one way or another, it will be possible to smuggle him all through the primary season and through a general election. But, really, in the era of unflagging scrutiny of candidates that’s asking for a lot. It worked in 2020, but that was an anomalous election, held in the midst of a pandemic, with in-person campaigning largely suspended. 2024 would be a very different sort of matchup—with Biden compelled to hit the campaign trail and with Trump (if Trump does turn out to be the nominee) playing his favorite role as an insurgent.

A divided primary featuring multiple mainstream candidates would be uncomfortable for Biden and for the Democratic establishment in general, but, with a matchup with Trump looming, the stakes are too high for the Democrats not to proactively attempt to choose the most electable candidate. The whole point of a presidential primary is that it’s a fair fight. If Biden really is the best candidate to win in 2024, then let him earn it.

Sam Kahn is an associate editor at Persuasion and writes the Substack Castalia.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I started a group about 6 months back on FB title Roy Cooper for President in 2024. Roy is my governor in NC and is well liked and won twice in a state that voted for Romney and twice for Trump. He is term limited so he cant run again in 2024. Southern centrist governors have done well for a first term- think Carter and Clinton. Andy Basheer fits that category.

Alas, I seem to be a devotee of St. Jude the patron saint of lost causes as nary a peep out of the governor but I hope maybe we can bang the pots and pans and get somebody other than the eccentric wing to run.

Democrats need to pray that Biden has a health problem sometime soon and has to drop out.