Bringing Human Nature Back In

Francis Fukuyama in the latest of our series “Why Liberalism.”

WHY LIBERALISM

“Why Liberalism” is an ongoing series by Persuasion in collaboration with the Institute for Humane Studies. Today, our own Francis Fukuyama takes us on a wide-ranging overview of the significance of human nature to liberal thought, and contemporary threats to the very idea that there is such a thing.

To receive future installments directly into your inbox, and sustain our ability to publish more series like this, please consider becoming a paying subscriber to Persuasion today!

And remember: Francis Fukuyama also oversees the American Purpose section of our magazine, the Bookstack podcast, and posts frequently on his “Frankly Fukuyama” blog. Chances are you have not yet opted into all of this great content—please do so today by clicking “Email preferences” below and sliding the relevant toggles.

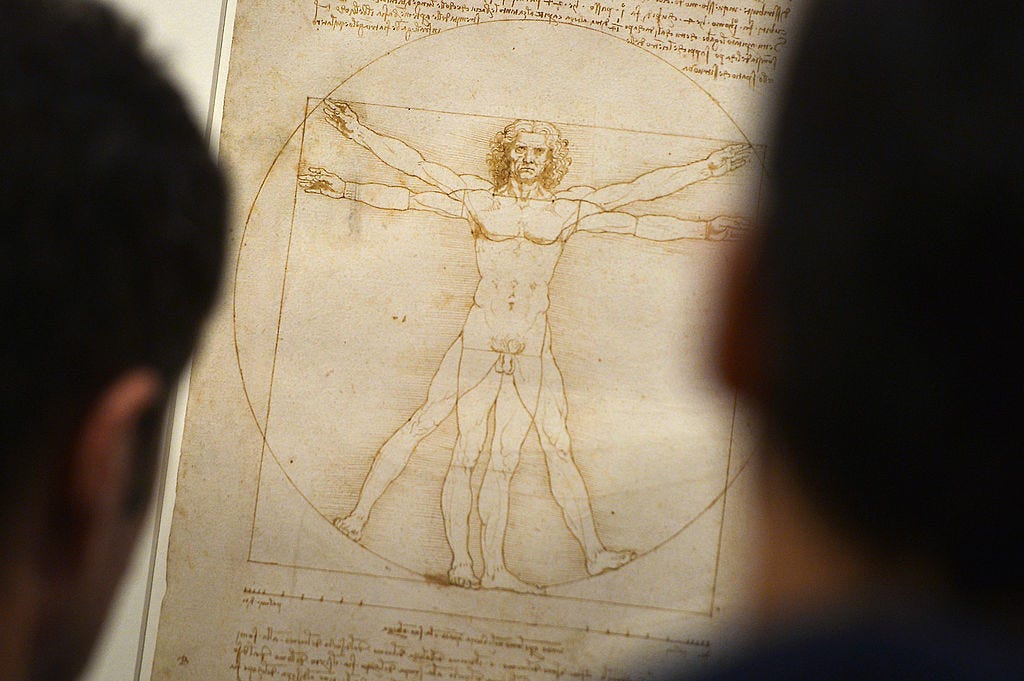

Human nature has been critical in the development of Western political philosophy, and hence of politics. Socrates in the Republic posed the question of what is true of humans “by nature,” and what is merely customary. Customs are subject to change and can be deliberately shaped by societies, while human nature has a permanence which gives it a priority with respect to human ends. To take one example, human languages vary across cultures, but the faculty for language is common to individuals in all cultures, Greek or barbarian, and the ability to use language has been closely connected to human reason and social organization.

Thomas Hobbes, one of the founders of modern liberalism, began his book Leviathan with a comprehensive catalogue of human passions, which could be understood as his understanding of human nature. Hobbes famously asserted that there were no natural moral rules, and that the war of “every man against every man” led to a state of violence and insecurity that made life “nasty, poor, brutish, and short.” This situation was in turn the product of two fundamental human passions, the desire for “gain” or the resources beloved by economists, but also a desire for “glory”—that is, for the estimation by other people of one’s worth as superior. Though Hobbes did not use Plato’s terminology of thymos, that is what he was talking about, and in particular, the dangers of megalothymia: the desire to be recognized as superior to other people.

Hobbes’ account of human nature then leads directly to his understanding of politics. The violence of the state of nature fuels the strongest natural passion, which is the fear of violent death. This becomes the grounds for his argument that the “first right of nature” is the right to preserve one’s own life. In the anarchic state of nature, human beings could not avoid threatening one another’s lives. The Leviathan, or state, was necessary to create a social compact by which each person gave up a little natural liberty for the sake of preserving his or her life. Security from the fear of violent death was a stronger passion than, say, the desire for a pleasant summer vacation or for a 40-hour work week, and therefore had priority in the hierarchy of basic rights. Hobbes’ “right to life” was the progenitor of Thomas Jefferson’s right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” asserted in the U.S. Declaration of Independence. This was the “natural law” tradition running from Aristotle through Thomas Aquinas up through Hobbes, Locke, and the American Founding Fathers.

Hobbes is rightly understood to be one of the founders of modern liberalism, even though his Leviathan was hardly what we would today describe as a liberal state. Most of the big political controversies of subsequent centuries revolved around alternative understandings of human nature, and therefore of the kinds of political systems that needed to be derived from them. For example, John Locke, who exercised enormous influence over the American Founding Fathers, had a softer view of human nature that encompassed a natural proclivity to acquire property, and to make it more productive. Private property emerged when human labor was combined with the “almost worthless things of nature,” and became the basis for market exchange and thus economic growth. Jean-Jacques Rousseau disagreed explicitly with Hobbes, arguing that “natural man” was not violent or greedy, but rather a timid, solitary creature who had within himself the capacity for happiness. The lust for resources and glory that Hobbes described came about only when early humans came together in societies and began to compare themselves to one another. Society rather than human nature was thus the source of competition, violence, and feelings of envy. Human happiness could be restored only by recovery of the authentic “natural man” that lay behind the customs and pressures created by an external “society.”

The differing assumptions about human nature represented by Hobbes and Rousseau have big implications for contemporary arguments over environmentalism and, indeed, the nature of human happiness. Hobbes presented a secular version of the Christian doctrine of original sin: human beings are by nature greedy, fearful, violent, and vain; it was only by coming together under a social contract that these natural passions could be kept under control. Rousseau, by contrast, reversed the valence of inside and outside: human beings are naturally good; it was only their entry into society that corrupted them and made them unhappy. The Rousseauian assumption is today shared by many anthropologists and environmentalists, who tend to believe that indigenous societies are more peaceful and environmentally protective than the modern industrial West.

For the last couple of centuries, many people in liberal Western societies have shared Rousseau’s assumption about the “natural goodness of man.” This is true insofar as they value inner authenticity, and believe that it is the pressures of “society” that suppress that authenticity and deny them the happiness they would naturally enjoy. In a Hobbesean world, growing up entails acceptance of the fact that one cannot do whatever one wants, and that a successful life requires conformity with social rules. In a Rousseauian world, by contrast, the inner self is constantly seeking liberation from stifling social constraints, whether the latter are enforced by a state, or simply by social custom.

Although they differed among themselves, these early modern thinkers’ theories of human nature laid the groundwork for modern liberalism. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau all posited that the state of nature consisted of isolated individuals pursuing their own ends, and that human societies emerged only later as people agreed to cooperate as a means of achieving those ends. The only form of human society that was natural was the family, where sexual desire drove men and women into mutual dependence. This view remains at the core of modern neo-classical economics: the fundamental assumption is that human beings are rational utility-maximizers who come to understand that they can increase their individual well-being by working with one another. This becomes the basis for Mancur Olson’s widely used theory of collective action, where social cooperation is primarily driven by individual incentives. In John Locke’s account of marriage and reproduction, the family was not grounded in emotional ties arising from human nature, but was rather a voluntary union based on a rational calculation of long-term self-interest.

Primordial individualism is thus an assumption about human nature that lies at the heart of modern liberalism, both political and economic. In this respect liberals broke with Aristotle’s view that man is a “political animal” by nature, who can only experience a flourishing life in a city. The individualist assumption would be directly attacked by thinkers on the left, beginning with Karl Marx, who held that human beings were by nature social creatures who sought collective rather than individual ends. Liberal individualism was seen to be an historically contingent phenomenon that appeared with the growth of modern capitalism, but which gravely distorted understandings of human happiness.

Liberalism’s individualist assumptions were attacked not just from the left, but from the right as well. The great English legal theorist Henry Maine already noted in the mid 19th century that what was known about early societies contradicted the individualist assumption: there was never a time, as far as the historical record showed, when human societies did not exist. There was no period of history characterized by the isolated individuals of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Following Charles Darwin and evolutionary theory, it became further clear by the 20th century that mankind’s non-human progenitors also lived in social groups of varying complexity. What distinguished the left- and right-wing critics of liberal individualism concerned the type of social group to which human beings were naturally attracted. For Marx and his followers on the left, it was large social classes like the bourgeoisie and proletariat, or, at the end of Marxist history, a communist state. For people on the right from Johann Gottfried Herder to Oswald Spengler to contemporary national conservatives, it was cultural groups from tribes to nations to civilizations. The specific beliefs underlying different cultures were variable, but there was a natural human proclivity to produce culture, and to live within a closed cultural horizon.

The discovery of DNA and the genetic code in the 1960s provided a heretofore missing biological account of inherited physical and behavioral traits. Given this, and the ubiquity of belief in human nature, it may seem surprising that there has been a huge amount of pushback against the very concept, and outright denials on the part of serious thinkers that human nature exists.

There were a number of reasons for this skepticism. In the first place, as knowledge of genetics increased, it became clear that our genetic inheritance interacts with our social and physical environment in very complex ways. Human beings are not robotically programmed to behave in determinate ways like certain animal species. Faculties may be rooted in the human genome, but their development could be extended, enhanced, or conversely constrained by how an individual is brought up and interacts with society. Geneticists discovered that certain genes are expressed only in response to specific environmental signals. It was therefore sometimes hard to say what core human capacities were “by nature.”

We know a lot more today about human nature than we did in the 18th or 19th centuries, not just as a result of advances in biology, but also because of research coming from archaeology, comparative anthropology, and indeed primatology. From the vantage point of the present, it is safe to say that the early modern liberal narrative about the state of nature was wrong in several respects. I presented evidence for this in the first volume of my Political Order series. Human beings are social by nature, but their sociability takes certain characteristic forms. The biologist William Hamilton’s theory of inclusive fitness posits that human beings—indeed, not just human beings but most sexually reproducing species—are altruistic in proportion to the number of genes they share with relatives. They are also strongly inclined towards reciprocal altruism, that is, the exchange of favors or benefits with close colleagues. This means that the most prevalent form of social life lies in community with a small circle of friends and family. This means that patrimonialism—that is, rule by friends and family—is deeply natural. By contrast, the kind of impersonal authority required by a modern state where officials are chosen on the basis of merit does not come naturally to political actors. For this reason, “re-patrimonialization” is a constant threat in modern political systems. We see this today as Donald Trump seeks to undermine the merit-based bureaucracy, relying instead on a close circle of trusted friends and family.

But this kind of small-scale sociability does not exhaust the human capacity for community. Human beings may have individual interests, but they are also by nature norm-following animals who are loath to deviate from the rules established by their peers. The willingness of individuals to comply with rules set by large hierarchies has been the basis for state authority ever since the invention of the first states some 6-8 thousand years ago. The rule-following proclivity explains why policemen are willing to carry out manifestly unjust orders against fellow citizens, or why millions of soldiers have gone to their deaths in battle. Thomas Hobbes’ belief in rational self-interest led him to argue that soldiers ought to desert their posts rather than risk their lives fighting enemies, and yet obedience has been much more characteristic of military organizations over the centuries than desertion.

More recent data also suggests that Hobbes may have been closer to the truth than Rousseau with regard to propensities of early peoples towards violence. The latter’s assumption about the “natural goodness of man” is unfortunately contradicted by a fair amount of empirical evidence: many hunter-gatherer societies have higher murder rates than contemporary American or Mexican cities, and evidence of bloody warfare extends backwards in the archaeological record as far as we can see. Humans are social creatures by nature, but their sociability is often driven by the need to organize violence. Stewardship of the environment appears to be due more to a lack of technological capacity rather than intention. The world’s megafauna were largely wiped out following the entry of modern humans into those regions where they existed.

So human nature exists, and is a powerful force shaping politics. The existence of human nature grounded the early liberal understanding of rights. Why then does it meet such resistance?

The reasons are moral and political, and are often byproducts of misunderstandings of human nature. Over the years, the question of what is biological and what environmental has been the source of enormous political controversy. Broadly speaking, conservatives have tended to take the side of biology, while progressives have argued that behavior is strongly conditioned by the surrounding environment—that is, “socially constructed.” Over the centuries, conservatives have believed that nations were rooted in common race and ancestry; that there was a racial hierarchy that legitimated slavery at home and Europe’s colonial domination of much of the rest of the world; or that women did not have the mental capacity or emotional stability to enter the workplace, vote, or become political leaders.

It is safe to say that these and other political uses of biology have been losing propositions. A lot of this was simply the result of empirical scientific research. A famous case from the 1920s involved the work of the anthropologist Franz Boas, one of the founders of modern cultural anthropology. Following the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, a school of “scientific racism” emerged, arguing that, among other things, the world’s races differed in average intelligence, with white, northern Europeans coming out on top. In the 1920s conservatives argued in favor of restrictions to immigration on the grounds that the groups coming to America during the great wave of the late 19th and early 20th centuries—Italians, Jews, Poles and other eastern Europeans—were less intelligent than the then-dominant ethnicity in the United States. This argument was based on a measurement of head sizes done by the U.S. Army as soldiers were being inducted to fight in Europe. Boas did a follow-up study that showed that the head sizes of immigrant children converged with those of northern Europeans when fed an American diet. Later studies of the so-called “Flynn effect” showed that average IQs were going up over time for population groups all over the world as a result of better diet and nutrition—at least until recently.

Controversies over the role of biology re-emerged big time with the rise of feminism in the 1960s. Many feminists were strongly on the social construction side, arguing that apparent male-female differences in either behavior or social outcomes were due exclusively to the way that girls were brought up in contrast to boys. Women had to be liberated from the social conventions that made it hard, for example, for them to enter a variety of professions from driving trucks and piloting airplanes to serving in the police and military.

But while biological arguments about what girls and women could or could not do were steadily debunked, there remained a core set of male-female differences that could not be overcome. Men and women obviously differ with regard to physical characteristics, which go beyond the fact that they have different reproductive organs. Height, upper body strength, longevity, and other features may be normally distributed for both sexes, and there will be individuals in the tails of the distributions that will outperform the vast majority of members of the other sex. But the medians of those distributions differ. So while any individual woman may be stronger or taller than any individual man, the characteristics of the sexes will not be the same in the aggregate. This is why male and female sports remain segregated to this day.

These differences very likely extend to psychological characteristics as well. In the 1980s evolutionary psychologists began to argue that male and female reproductive strategies differed, not just among human beings, but among very many sexually-reproducing species. Men tended to be more promiscuous than women because that was their optimal strategy for getting their genes into the next generation; women by contrast needed stable homes in which to raise their children to adulthood. Adolescent women are also less inclined to risk-taking, which is why the vast majority of crimes are committed by young men in cultures all over the world.

The idea that any behavioral trait could be explained biologically did not sit well with many feminists. The sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, who argued that gender differences were biologically based, had a pitcher of water dumped on his head at a conference by an activist shouting “You’re all wet!”

There is another, even more fundamental reason why progressive liberals resist granting significance to human biology: it represents a potentially insuperable limitation of human autonomy.

At the core of modern liberalism is an assertion of the equality of human dignity, based on a posited universal human capacity for choice. Human beings may differ in terms of intelligence, strength, skin color, and gender, but all are deemed moral agents who have the ability and the right to make choices about their own lives—rights to speech, belief, association, and the like. Protecting that autonomy has been regarded as the moral core of a liberal society. In early modern Europe, autonomy was understood as the right to make choices within pre-existing moral frameworks, frameworks established by various religious traditions. Freedom of religious belief was therefore one of the key values protected by rights like the U.S. First Amendment.

Over time, however, the sphere of autonomy expanded relentlessly to include not just the ability to make choices within a moral law defined by an existing religious tradition, but also to choose one’s framework and even make up moral rules for oneself.

This is nowhere more evident than in the sphere of sexuality, gender, and family life. Many countries have legalized abortion, which is typically framed as a way of protecting the autonomy of women to control their own bodies. But the final frontier in the denial of the significance of biology is the contemporary transgender movement. Many transgender activists, supported by a good part of the medical establishment, assert that gender is wholly unrelated to biological sex, that is, to one’s XY chromosomes. Rather, it is a matter of individual choice, much as one might choose a new name or a place to live. They don’t want to be told that their genetic endowment will have powerful effects on their gender identity.

The notion that there is a strong underlying relationship between biological sex and gender identity has become one of those verboten ideas in certain liberal circles during the 2010s and ’20s, a prohibition that has been rigorously enforced by many transgender activists. The idea is not a very plausible one, however. It doesn’t make sense to think that people were choosing their gender identities over the centuries solely as a result of social pressure: the rootedness of human beings in their biological sex is a necessary precondition for reproduction and family life to take place. It would undermine Darwin’s theory of natural selection, not to mention his whole theory of sexual selection, which goes down the drain under these conditions. A liberal society must respect the choices and protect the rights of transgender people, but this is very different to the more extreme demands of activists who wish to enforce a general rejection of biological facts.

Finally, while technology promises to take away the limitations of human nature, this is a false promise. I believe that we are moving into dangerous territory here. Human beings are not disembodied wills floating in space that can choose to land in any shape or form they choose. Our human experience, and therefore the ends and goods that we seek, have been deeply shaped by our physical bodies and the strengths and limitations that they entail. This is why I wrote my 2004 book Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. Human beings have been using technology to enhance their physical and mental faculties continuously throughout history. We are faster, stronger, see better, travel further, and live longer through technologies from eyeglasses to automobiles to vaccines. Biomedical technology can already shape behavior and outcomes through surgery, drugs, and other interventions. But the emergence of genetic engineering made possible by technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 promises much more fundamental changes to those underlying faculties that may one day alter our understanding of political rights.

Do we really want to be able to freely change our underlying natures, to make human beings more or less aggressive, more or less compassionate, more intelligent or more servile? We may not like the proclivity for risk-taking and violence, but what unanticipated consequences may flow from an effort to breed it out of the human race? And who is it that will be exercising the power to decide these issues, decisions that will affect not just subjects in the present generation, but all of their descendants? Will these powers be exercised by wealthy elites, who can then give their descendants a leg up in social competition in centuries to come?

Liberals need to recognize that while autonomy is a human good, it is not the sole human good that trumps all other ends that people choose. Part of the human experience lies in coming to terms with limitations, both those that apply to us as individuals, and those that are true of human beings as a species. Indeed, those limitations are what link us in communities. Many people deliberately want to live within a religious or cultural tradition that binds them in communities, even as it restricts their freedom of individual choice.

As the Latin poet Horace said, “You can throw nature out with a pitchfork, but it will always come running back.” We will never become gods, and may learn that lesson only as we approach our 200th birthdays with the diminished faculties of five year olds.

Francis Fukuyama is the Olivier Nomellini Senior Fellow at Stanford University. His latest book is Liberalism and Its Discontents. He is also the author of the “Frankly Fukuyama” column, carried forward from American Purpose, at Persuasion.

The “Why Liberalism” series is a project by Persuasion in partnership with the Institute for Humane Studies (IHS). IHS is a non-profit organization that promotes a freer, more humane, and open society by connecting and supporting talented graduate students, scholars, and other intellectuals who are advancing the principles and practice of freedom. For additional information and details, media, programmatic, and funding opportunities, visit TheIHS.org.

Also from “Why Liberalism”:

A People’s History of Free Speech

On the Greek origins of the First Amendment, and what we lose when we lose the inclination to speak truth to power.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I was inoculated against woke nonsense by Steven Pinker's "The Blank Slate." This essay is an excellent "booster."

An excellent essay, and one that I will reference in the future for its description of human nature theories in political history.

Unfortunately, the section about "scientific racism" fell into the same trap the author is arguing against. There are still brain size differences between groups, IQ tests have never shown Whites as a the top performing group (that would be Ashkenazi Jews and then East Asians), and after IQ testing was improved (90+ years ago) they have always shown a persistent gap between different groups, even as all groups have improved (Flynn Effect).

Ironically, the IQ explanation for group equity gaps - the one thing that might actually destroy woke ideology - is that one thing that intellectuals fear to discuss honestly.

“You can throw nature out with a pitchfork, but it will always come running back.”