Law ≠ Power

Legal academia helped pave the way for Trump’s dangerous assault on the rule of law.

Trump has declared war against the American legal system—and, for the most part, institutions have caved to him. Collectively, nine firms have agreed to donate almost a billion dollars in legal fees to the administration’s preferred causes. As heinous as Trump’s actions are, and without minimizing the severity of his attacks, it is important to acknowledge an uncomfortable truth—that legal institutions themselves bear a significant measure of blame. In the recent past, law schools and the profession as a whole have had an unfortunate tendency to portray the law as nothing more than an instrument of power. And the profession is now experiencing buyer’s remorse in seeing how similar that doctrine is to Trump’s vision.

The core principle of the rule of law is that those in the legal profession act as a bulwark against oppression, as gatekeepers of a legal system that, while imperfect, divides rights and responsibilities fairly, treats litigants of all types equally, and holds powerful actors to account.

But, in a timeline stretching back to—let’s say—the 1970s, law schools have instead focused on structural inequities. The “in” doctrine is to teach students that law is a tool for oppression, a system rigged to ensure racial and other imbalances remain intact. Rather than acting as key players in a neutral system, lawyers, according to this theory, are a part of the problem. Unless they represent the “right” clients and seek to use the law to fight pernicious hierarchies and obtain social justice—a substantive idea of the public good based on a distinctly progressive vision—they contribute to existing injustices. The ascendant left-wing view of lawyering assumes that lawyers are morally implicated by their client’s goals—a notion that is a stark repudiation of the liberal democratic view that even the most despised clients deserve representation.

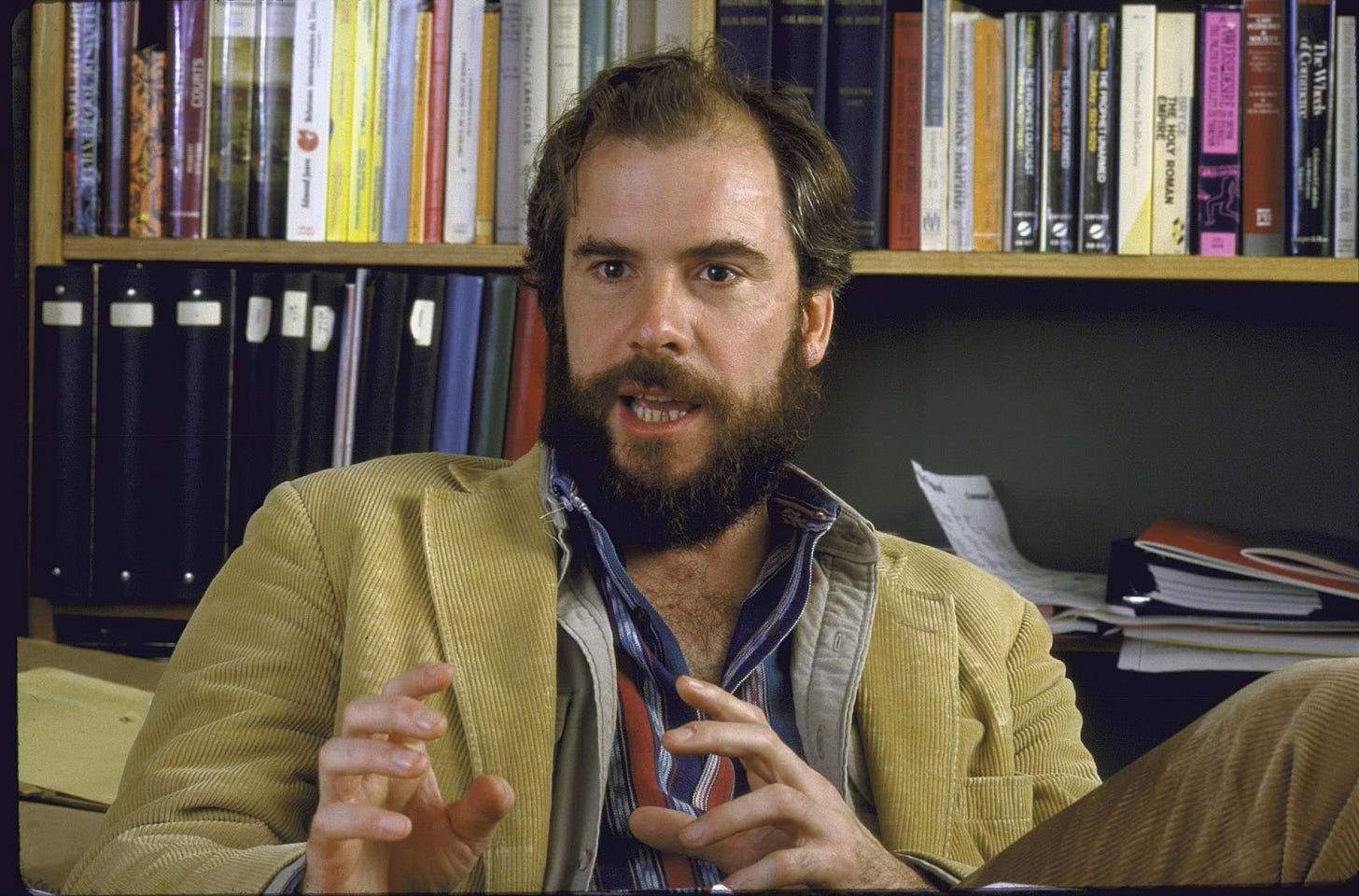

We can trace the origins of this view to the critical legal studies movement that emerged primarily out of Harvard Law School in the 1970s. Roberto Mangabeira Unger, one of the movement’s most prominent advocates, described his work as being the effort to rebuild legal institutions as “fragmentary and imperfect expressions of an imaginative scheme of human coexistence rather than just as provisional truce lines in a brutal and amoral conflict.” Duncan Kennedy, another founder of the movement, viewed critical legal studies as being “concerned with the relationship of legal scholarship and practice to the struggle to create a more humane, egalitarian, and democratic society.”

Critical legal studies assumes that law is infinitely malleable but tends to be nothing more than a lever used by those on top to perpetuate their power. It is both highly cynical and highly idealistic. It holds that the fundamental work of the legal profession should be to wrench the law from the hands of the powerful and use it on behalf of the marginalized.

That theory has significantly affected legal education and the profession as a whole. “Every corner you turned and every closet you opened at the law school, there it would be, in some sort of zombie or ghost-like form,” said Harvard Law School professor Jeannie Suk Gersen, who is sympathetic to the movement, while discussing her documentary on the subject. In its implications, it abrogated the very premise of “the rule of law.” It is no exaggeration to say that legal academics have trained generations of lawyers that there is no such thing.

Given that decades-long background, it shouldn’t be such a surprise to see, as if through a fun-house mirror, Trump espousing similar tenets. Trump’s approach to the law is neatly summed up in his comment during his first term, “Where is my Roy Cohn?” Invoking the infamous and ruthless attorney for Senator Joe McCarthy, Trump succinctly expressed his view that law is a source of power, rather than a real constraint. That view is, at a structural level, similar to the dominant view on the left as promoted by the legal academy—that law is a tool, a means for those in power to consolidate control. Both conceptions are a far cry from a vision of law as embodying fundamental neutral principles of procedural fairness and substantive justice.

The result of this sweeping change in conception is a cataclysm for the legal profession—which is playing out at a rapid clip. Rather than seeking to destroy law firms, the purpose of Trump’s executive orders is even more dangerous: to bend them to his will and redistribute elite talent to MAGA’s causes. Recognizing that educated individuals and the institutions they populate are a powerful force, Trump is attempting to use executive power to scare them into submission. No written agreements have been disclosed, but Trump describes the uncompensated services that the firms have agreed to provide as “damages” to MAGA. He has bragged that he will use the lawyers to negotiate trade deals with foreign countries and help coal miners with their leasing. Some advisors are even considering using the promised pro bono hours to force these law firm lawyers to assist Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), or set them to work for the Justice Department.

Trump’s misuse of the law should worry even the least alarmist observers. The MAGA movement has attacked the rule of law on multiple fronts, including undermining DOJ independence, threatening judges with impeachment, and ignoring court orders. But the singling-out of law firms is perhaps the most brazen attempt to eliminate legal constraints on its agenda and insulate allies from accountability. For courts to fulfill their key constitutional role as a check on government abuses, they depend on an independent legal profession to represent unpopular clients and bring cases before them.

Regardless of whether law firms cut a deal or go to court, they face a new challenge in deciding which clients to represent and significant conflicts in how to pursue their clients’ interests so as to avoid the president’s ire in the future. Because firms will be unable to take on future clients due to these conflicts, Trump has usurped not only the massive pro bono hours but also the lawyers’ time and work for other causes. While firms have historically struggled with the economic consequences of representing certain clients, like tobacco companies, or taking on controversial causes, like gun rights, the stakes of challenging MAGA allies or their agenda have suddenly become higher. This may well mean that clients whose interests are at odds with the president’s will find it hard to hire the most accomplished lawyers.

Several courts have already issued injunctions against these executive orders and the constitutional arguments against them are substantial. The lawsuits allege that the executive orders retaliate against firms for protected speech, illegally discriminate against lawyers and clients based on their viewpoints, and violate due process. Insofar as they prevent criminal defense counsel from negotiating effectively with the government, they also deprive individuals of their Sixth Amendment right to counsel. Finally, there are strong claims that the orders violate the separation of powers because only the judiciary has the authority to discipline attorneys.

Even if the courts strike down the executive orders, however, significant damage is already done. The law firms that have capitulated face backlash from clients, lawyers, and critics across the legal community. Those that are fighting the executive orders have suffered substantial financial consequences, all before the courts resolve the legal challenges involved. The administration has flexed its muscle, displaying how much power it wields even before courts can step in. To effectively stop this campaign, the legal battles must be accompanied by public outrage. But the legal profession, like many other targets of Trump’s ire, is in a poor position to publicly defend against these allegations and so Trump’s rhetoric may not sound as absurd to some as it should.

Trump has defended his orders by insisting that he is simply correcting a corrupt liberal bias among elite lawyers and the legal profession generally. In a Truth Social post after the firms began to cut deals to avoid the crippling orders, Trump boasted that he was “build[ing] an unrivaled network of Lawyers, who will put a stop to Partisan Lawfare in America, and restore Liberty and Justice FOR ALL.” The Trump administration needs the guise of lawfulness and so it masks its attack on the rule of law as the opposite: an effort to restore fairness to a warped and biased system. In other words, like the Department of Justice and elite universities, the legal profession, according to Trump, was stacked against him and his supporters. In Trump’s rhetoric, the orders are correcting this abuse.

For the most part, this allegation is absurd. Law firms are not biased against Trump or filled with progressives who despise him. Law firms are businesses that serve clients and while many of them take on pro bono cases that may align with liberal causes, they have not dedicated their practice to attacking Trump and his allies, nor does their work for large corporations advance a liberal agenda.

The challenge, though—and something that the legal professions must wrestle with—is that Trump is not entirely, altogether wrong. Throughout the first Trump term and in its aftermath, segments of the legal profession played into the hands of those who allege liberal bias. Many powerful and prominent members of the profession lined up against Trump. Pundits peddled novel and sometimes unreasonable interpretations of the law and legal ethics to criticize the president and his allies. Organizations popped up with the sole mission of seeking discipline against Trump’s lawyers, often calling for punishment of protected speech. To be fair, these critics may have accurately seen Trump as a threat to the rule of law, but, rather than point this out, they had a tendency to use the law as a weapon against him.

The goal, which can be traced all the way back to the change in the conception of the law in left-wing legal circles in the 1970s, was to use the law as a weapon to unseat powerful adversaries. Like universities and the media, the legal profession was significantly weakened by its own inability to maintain its neutrality and promote the need for mediating institutions. Caught in an effort to address inequality, many prominent voices within the legal profession became obsessed with delegitimizing the justice system instead of championing its critical importance in a liberal democracy. Having cast the law as nothing more than a tool of the powerful, it is hard to turn around and criticize the legitimately elected president for using it as… just that.

Rebecca Roiphe is the Joseph Solomon Distinguished Professor of Law at New York Law School. She is writing a book on the history of legal education in America since 1970.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Can we talk about the assaults on the constitution under covid, shutting down the country, closing schools and businesses...pressuring facebook to censor true posts that could contribute to vaccine hesitancy.? Allowing vaccine mandates for people to keep their jobs. This included mandating an experimental new vaccine even to pregnant women.. The list goes on.

Myself, as a regular Jane, an independent, two time Obama voter, I just tune out this drama about undermining the rule of law. In my view the rule of law was dramatically undermined throughout the covid pandemic and by the Biden administration. It all seems so polticized. I just don't believe democratic whining anymore.

That said, the one thing that upsets me is Trump deporting people who protest against the war in Gaza. That is a clear assault on free speech. If only the Biden administration hadn't also been aggressively assaulting free speech on the subject of covid, transgenderism, etc.. See Matt Taibbi and Paul Thacker's work on the disinformation industrial complex.

Critical legal theory analyzing law and its historic application as a tool of the powerful, may be described as 'cynical' ...but is it *wrong* (in the sense of, 'untrue')? Roiphe doesn't quite seem to say so. If the argument is that it is wrong, or at least incomplete, please make that argument.