Until the Democrats Adapt to New Media, They Will Never Win

The party’s new YouTube show is embarrassment’s very deepest pit.

It may not exactly have been a bellwether district or battleground state, but since it was the first election in my living memory, I can’t help but apply a certain amount of political analysis to the swing of my first grade class in our 1992 mock election—where we went very heavily for Clinton. We were in a very progressive area, but that mattered less than might have been expected. Ross Perot’s tax cuts actually sounded pretty good to us, and a lot of us were in our fighter planes stage, so H.W. Bush’s execution of the Persian Gulf War mattered a great deal as well. But there was one overriding wedge issue, one unforgivable sin, which really tipped our election, and that was that Dan Quayle, Bush’s VP, had misspelled the word “potato” and, except for the real flat taxers and F-15 fanatics among us, that proved the overwhelming difference.

What we might have missed in our post-mortem analysis of that election—what in fact it took a very long time for me to realize—was that the reason Quayle’s misspelling weighed so heavily in our minds wasn’t exactly the event itself as the architecture of media at that time. Quayle was a particular favorite of Saturday Night Live—actually, if you look back at SNL episodes from this period, it’s fairly rare that you don’t have Quayle getting confused in the background of a speech or crying on Bush’s shoulder. SNL had weight because it wasn’t partisan—presumably, all that it was interested in doing was being funny—and of course it reached around 12 million households.

In retrospect, SNL was far from non-partisan—the people who worked on it largely lived in New York, and they tended to be Democrats, as were the executives and talent in the networks as a whole. And it was that architecture—much-maligned by Republicans as the “mainstream media” (although of course nobody was listening to them since they didn’t have access to the MSM)—that gave Democrats an insuperable advantage for decades. If I were to taxonomize the close elections over the past half-century, I might divide them between the “debate” elections and the “SNL” elections. In the debate elections, the critical moment tended to come in one of the debates—George H.W. Bush checking his watch, Candy Crowley correcting Mitt Romney over a disputed fact—while in the SNL elections, Chevy Chase turned Gerald Ford, an All-American college football player, into a klutz, and Tina Fey essentially wiped out Sarah Palin’s legitimacy as a vice presidential candidate by declaring “And I can see Russia from my house.” More than I think any of us are really prepared to admit, it’s moments like these that stick in the minds of swing voters and are the deciders in close elections. When the Republicans won, they tended to get around the media machine with advertising and highly successful repetitive messaging, e.g. “morning in America,” Willie Horton, or the Swiftboat Veterans’ accusations against John Kerry.

All of this was built into the political landscape and went largely unquestioned for decades. The Republicans would hammer away with their channels, but the Dems had the insuperable advantage of the networks—and, above all, its comedy—to tilt the playing field in their direction. For a long period during the 2000s, when the Democratic Party establishment seemed largely to have lost the ability to connect to swing voters, it was more or less Comedy Central that acted as the real locus of the Democratic Party—it was very difficult to watch Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert and not end up feeling that Republicans were humorless fanatics and that the Dems, if absurd in their own way, were at least roughly on the side of sanity and good governance.

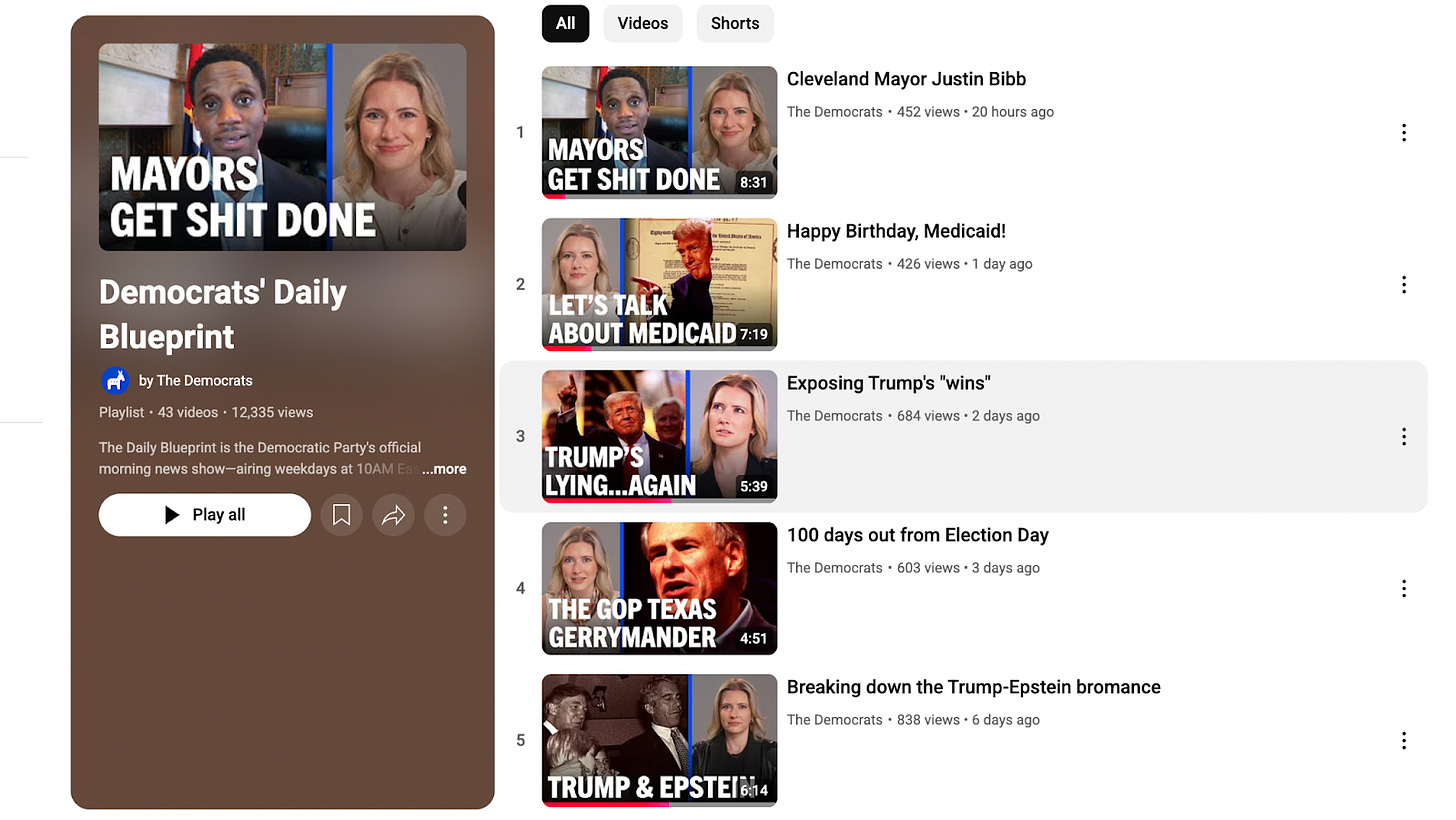

But what has happened, with a change-over in the structure of informational flows over the past decade, is that Democrats have lost that advantage—and still somehow haven’t processed the change or how catastrophic it is for their party’s prospects. If we’re looking for an X-Ray of how bad it’s gotten, the place to look is The Daily Blueprint, a new show launched by the Democratic Party to spread its message. The Daily Blueprint is a brain child of Ken Martin, the new chair of the DNC, and I can only applaud its intent—to try to use the resources of new media to reach a new generation of voters—except that it’s awful. The Daily Blueprint lives on YouTube. It seems to have no real push behind it, whether in social media or new media (I came across it from the last paragraph of a disparaging New York Times article on Martin’s tenure), and after 41 videos it has racked up a grand total of 12,089 views. Videos seem to average around 300 views.

The problem isn’t just distribution or a roll-out strategy that seems to be limited to talking to The New York Times’ National Desk. There’s a fundamental misconception about what new media is and the kind of tone it needs to strike. “The Daily Blueprint” is shot in a studio with what The New York Times somewhat optimistically calls “high-end production” and with the kind of cheery graphics and bass riffs that take you back to the glory days of local cable news, if not to that dire moment in a company-mandated social event where everybody is suddenly forced to talk about what a great time they’re having. Hannah Muldavin, the usual host, is the DNC’s Deputy Communications Director—and she seems like, probably, a really good deputy communications director, always on-point, on-message, and giving the spiel with the kind of morning meeting briskness that makes you look around for glazed donuts and a company-provided box of joe. It’s smiley, it’s barbed. There’s nothing about it that doesn’t ooze insincerity—and it is deep-fried in that signature Democratic Party smarm, the kind of thing that makes politicians unable to keep from referring to planted audience members by their first names throughout a town hall, and that sends off sonar pings in the minds of Democratic Party operatives every third statistic or so to remind them to be more relatable.

Take, for instance, Muldavin’s dissection of Trump’s “wins,” which starts with bracing stats about his trade deals, drug price plan, and attempt to reduce gas prices, before getting to the kicker, the fact that he cheats at golf. “We have a grifter-in-chief as president … someone who cheats at golf on his own courses,” she says, cuing up the smoking gun video. “Take a look here. See the guy in red? He’s going to throw a ball out. It’s incredible,” she concludes with the kind of broad psuedo-astonishment of an actor very, very close to landing their first Law & Order guest appearance.

Or take the feature on Juneteenth—a rare break from all the charts and talking points—which covers only so much of the holiday’s history before the interviewee, squinting at the teleprompter lest there be any hint of spontaneity here, says, “Unfortunately, this year, Juneteenth is also a reminder of what is at stake for black communities at a time when … Donald Trump clearly isn’t up to the task.” Or take the downward-spiraling energy of an interview where Muldavin, with straining professionalism, declares that she’s “so excited” to meet Virginia Lieutenant Governor candidate Ghazala Hashmi, only for Hashmi to pop onto the screen with exercise equipment in the background and to mouth platitudes in a monotone.

I don’t exactly blame Muldavin, who is doing her cheery best, for what’s lacking in the Democratic Party’s channel. The whole thing is an exercise in what you can do in television without humor, without reportage, without emotionality, without variation—and the answer is: not very much. Muldavin is a political operative and she’s carrying over her training beyond the press release and the phony letter-to-the-editor. But the operation as a whole clearly just hasn’t adapted to the new media landscape, where the coin of the realm is sincerity. As Joe Rogan put it to Trump during their 2024 interview:

People were tired of someone talking in this bullshit pre-prepared politician lingo. And even if they didn’t agree with you, they at least knew, “Whoever that guy is. That’s him. That’s really him.” When you see certain people talk, certain people in the public eye, you don’t know who they are. You have no idea who they are. It’s very difficult to know. And you see them in conversations. They have these pre-planned answers. They say everything. It’s very rehearsed. You never get to the meat of it. One of the beautiful things about you is that you freeball, you get out and you do these huge events and you’re just talking.

That’s the Trump playbook. It’s loose and it’s casual and it involves a saturation of every possible communicative outlet so that Trump always becomes the main character of the story. In 2013, when he was telling GOP leaders his plans for entering the presidential race, Trump explained himself as follows: “I’m going to suck all the oxygen out of the room. I know how to work the media in a way that they will never take the lights off of me.” And that remains the single best description I’ve seen of Trump’s style of leadership and governance, updated only slightly for the advent of new media.

It’s been this way for years now. It’s really not very hard to figure out why Trump is as successful as he is—or to imitate it. The young stars of the Democratic Party, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Jasmine Crockett, Zohran Mamdani, are getting where they’re getting because of their facility with social media and their willingness to embrace the new style where “messaging,” “discipline,” and the projection of competence matter far less than visibility, frequency, and the creation of a narrative around oneself.

But read what the Democratic Party itself is up to and it’s like all the cutting-edge ideas of 1956. Ken Martin has been increasing investment in state parties (including in solid-red states that the Dems have no hope of ever winning), organizing a hundred town halls (!) in Republican districts, and organizing a post-mortem to understand the cause of the 2024 defeat—although that post-mortem was designed to leave out anything connected to Biden’s decision to run again or to Kamala’s strategic choices. In as close to just withering sarcasm as The New York Times gets, the paper noted that the autopsy “will avoid addressing some of the likeliest or leading causes of death” and “is something like eating at a steakhouse and then reviewing the salad.”

But the autopsy did actually get somewhere. According to preliminary reports, it raised the fair point that the Democrats’ “advertising approach was too focused on television programs to be effective” and was also too tame in going after Trump. Which, to be honest, I could have told you too without having gone through the whole process of a formal autopsy. What that approach is based on is the common-sense wisdom within political circles that young people don’t really vote, and swing voters are sort of unreliable, and that the thing to do is to keep hammering away at older voters and to make sure that one’s base turns out. But that works in a relatively stable political climate. What happened in 2024 is that the Dems faced a 10-point swing of young voters away from them (15% among young men)—which is of course a double-plus bad because it means that not only are the Dems losing a key constituency but they are losing a constituency that will only get older and more powerful and that they have no obvious means of regaining because they have lost the tools of persuasion for younger voters. Back in the days of MSM dominance, it wasn’t just that the Dems’ message of an optimistic future seemed intrinsically to appeal to younger voters; it was that they had SNL and Jon Stewart and everything that was hip in media appealing to those voters. Stephen Colbert’s recent cancellation at CBS puts a pin in that whole era.

In one of the lamer elegies for the 2024 election, Michael Tomasky of The New Republic put the blame on “the right-wing media” which “sets the news agenda in this country and ... fed their audiences a diet of slanted and distorted information that made it possible for Trump to win.” Just Tomasky’s framing of this encapsulates the whole problem with the Democratic/liberal view of the world. What does it mean to “set a news agenda”? Isn’t “news” supposed to be “journalism” and in theory agenda-free? Is the right wing not allowed to have their own sources of information, or does the very existence of a right-wing perspective brand it as “slanted and distorted”?

But, as is always the case with wrong-headed ideas, Tomasky is in possession of a grain of truth—in this case, the fact that the MSM’s control of the airwaves has ended and the constellation of right-wing sources is a force to be reckoned with. What that means, though, is not wishing it away, which seems to be Tomasky’s action plan; not browbeating tech platforms to “disfavor” or actively censor disliked narratives, which was SOP in the late 2010s/early 2020s; not whipping out the 1956 playbook and seeing how many seniors the party can get into a room in a red state; not yelling at The New York Times whenever it criticizes Democrats; but doing battle in the landscape of the new media—and winning.

It’s the winning that’s of course the crucial part. And, unfortunately for the Dems, they are starting the race in the new media sphere very much behind. They have lost Twitter. Bluesky seems too much of an echo chamber to really reach undecideds. They always seem to be too decorous to wade into the conspiracy-tinged discourse which is what people really want to talk about. The much-derided “manosphere” has produced the most steadily popular media stars out there, and those figures have a tendency to be deep-dyed in resentment for the culture of scolding and cancellation on the Left. The calls for a “left-wing Joe Rogan” profoundly misunderstand how a Joe Rogan-type figure is created and elide how badly Democrats misplayed their hand with the actual Rogan—pretending that an independent-minded heterodox figure was somehow alt-right and then declining to compete for the swing voters he had unique access to. At the time of writing, the party is at an absolute nadir and has managed to show up to a knife fight armed only with Hannah Muldavin.

The good news—we have to scrape for good news here—is that the tools of the new media are changing so fast that it’s possible to rapidly adapt to them. Gavin Newsom, who was for years the Democrats’ reigning prince of smarm, managed to rebrand himself in record time as your cool-uncle-with-questionable-friends for his YouTube show “This Is Gavin Newsom.” (It’s noteworthy, by the way, that Newsom’s viewership numbers, which peak at 900,000 when he interviews right-wing firebrands like Charlie Kirk, Steve Bannon, or Michael Savage, drop to four or five figures when he listens to the voice of prudence and speaks to people who are safely in the Democratic camp.)

And stars like Mamdani and Crockett seem to be able to appear out of nowhere with a handful of viral-ish social media moments. What that shows is that the ideas matter less than one might think—and what matters is one’s willingness to hop in the back of a cab and talk to the driver for a social media video or to begin all the words in one’s sentence with the letter ‘v’. You don’t actually have to be in favor of government-run grocery stores, as in Mamdani’s proposal, to embrace new media and to figure out its rhetoric. Moderates can do it too. The Daily Blueprint, on the other hand, may well be remembered as the party’s absolute low point—trying to use the stilted language of press releases and talking points in an era of personality politics. If the Democrats can’t adapt from this, and can’t learn to talk to young people again, then the party will struggle to win a big election anytime soon.

Sam Kahn is associate editor at Persuasion and writes the Substack Castalia.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

People do not like being lectured to, even when it's subtle. People don't like liberal virtue signaling. Many of us don't want to hear about structural racism; we work with people of all races and everyone gets along well. We don't want to hear about how trans people are so persecuted. We are pretty sure that the only places in America where trans people would actually be in physical anger are gang dominated neighborhood in cities . Probably not white gangs. We don't want to hear about climate change from people who vacation in Europe every year.

The Democrats are where a party should be that hasn’t had a new idea since FDR or, more sympathetically, LBJ. Also, I am 74 years old and haven’t watched network or cable TV for about 5 years.