Britain Has Forgotten How to Be Free

The country that gave the world liberalism now treats free speech as a dangerous luxury.

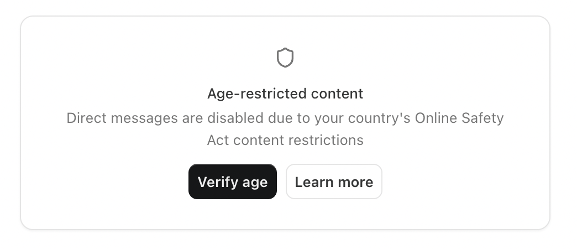

This week, I received a private Substack message from a Persuasion subscriber. Assuming it was a query about their subscription or the podcast, I attempted to open it—only to discover that it was blocked unless I provided evidence that I am over the age of 18. The UK’s Online Safety Act (OSA) has struck again—leading Substack to block all private messages unless the recipient can verify their age.1

Over the last 18 months, the grip of the OSA has become more apparent to internet users with each click. The law was passed by the British parliament in October 2023 but came into effect in stages, the last of which was in July 2025. Among other things, it requires tech companies to take action against illegal content on their platforms, such as child sexual abuse, revenge porn, and fraud. Concerningly, however, the OSA also requires tech companies to protect children from content that is not illegal, but which is nevertheless deemed “harmful.”

The two categories of legal-but-harmful content are worryingly fluid. “Primary priority content” includes pornography and content that promotes suicide, self-harm, or eating disorders. “Priority content” includes content that children “should be given age-appropriate access to,” such as “bullying,” “abusive or hateful content,” and content depicting or encouraging “serious violence or injury.”

In practice, this means that all internet users in the UK wishing to access content that is legal but “harmful” must prove that they are over the age of 18. This may be done through facial recognition, uploading a photo of a government-issued ID, or credit checks.

It also means that companies such as Substack, out of caution, slap blanket bans on certain types of content (such as direct messages) that may not be in any way harmful. Chris Best, CEO of Substack, has voiced concern about the OSA, writing:

In a climate of genuine anxiety about children’s exposure to harmful content, the Online Safety Act can sound like a careful, commonsense response. But what I’ve learned is that in practice, it pushes toward something much darker: a system of mass political censorship unlike anywhere else in the western world.

On top of the chilling effect of the OSA, there are serious privacy concerns. The data uploaded by users to verify their age—containing sensitive information such as passport photos—is stored in vast, potentially insecure databases. This was highlighted by a recent data breach into the third-party service used by Discord to confirm users’ ages. While the identity of the hackers was not confirmed, Discord claimed it was an extortion attempt and that the total number of users whose sensitive information was exposed was around 70,000.

The desire to protect children from harm is understandable. There is a huge amount of bad content online, and it can have real-world consequences. For example, young people with eating disorders have long been exposed to pro-anorexia communities, in which users share tips and “thinspiration” images to encourage each other to become even more ill. Such groups are pernicious, often reappearing elsewhere on the internet once they are shut down. Nobody should want children to be exposed to such communities.

But any attempt to protect children online must also be balanced against the right to freedom of expression for adults. In this, the OSA has gone too far—particularly since it has been introduced in a context of increasing restrictions on speech in the UK.

Take the rise of “non-crime hate incidents” (NCHIs), which for years have been used to undermine free speech in the UK. NCHIs are defined as “any non-crime incident which is perceived by the victim or any other person to be motivated by hostility or prejudice.” They are logged in police records and may be flagged in a background check. NCHIs were introduced after an inquiry into the high-profile racist murder of teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993, with the aim of tackling criminal abuse. The idea was to help the police map out where policing resources should be prioritized and prevent incidents that “could escalate into more serious harm.”

While data about this policy is very patchy, the introduction of NCHIs does not seem to have had the desired effect. According to a report by the think tank Policy Exchange, “There is currently limited, if any, evidence to demonstrate that the large-scale recording of NCHIs has enabled police officers to prevent the ‘escalation’ of situations into serious criminality.”

And, until recently, all that was required to log an NCHI was that someone felt they had been targeted. This changed following the case of former policeman Harry Miller, who had an NCHI logged against him for transphobia after he tweeted, among other things: “I was assigned mammal at birth, but my orientation is fish. Don’t mis-species me.” In its judgment, the Court of Appeals highlighted the “chilling effect” such legislation has on free speech and expression, and in 2023 new guidelines for NCHIs were published, emphasizing that NCHIs should only be logged in cases where a more objective standard of “hostility or prejudice” is met.

However, this has not stopped NCHIs being used to silence people. In the year up to September 2024, around 14,000 NCHIs were recorded in England and Wales. In August 2025, gender critical journalist Helen Joyce discovered that, a year earlier, she had been reported for a NCHI after referring to a transgender co-panellist as a man and a “fetishist” due to comments the individual had made during the panel. Despite logging the incident in their records, the police never told Joyce about it.

Around the same time, Irish comedian Graham Linehan was arrested at Heathrow Airport on suspicion of inciting violence on X, with posts such as, “If a trans-identified male is in a female-only space, he is committing a violent, abusive act. Make a scene, call the cops and if all else fails, punch him in the balls.” The charges were dropped, and the Metropolitan Police announced afterward that it would no longer investigate non-crime hate incidents. In December 2025, amid growing backlash, police leaders confirmed that they would recommend NCHIs be scrapped in favor of a “sensible” new approach that only focuses on the most serious “anti-social behavior.”

But this does not mean that threats to free speech in the UK have gone away.

In July 2025, a direct action group known as Palestine Action was banned under the Terrorism Act 2000, after activists broke into RAF Brize Norton and damaged military transport aircraft alleged to be supplying weaponry to Israel. The decision to ban the group was condemned by human rights experts.

Shortly after, the group organized a sit-in protest in Parliament Square, in which protestors held up signs reading, “I oppose genocide, I support Palestine Action.” Over 500 demonstrators were arrested, 112 of whom were over 70 years old, and by October 2025, over 2,000 people had been arrested simply for holding placards supporting Palestine Action. (The proscription of Palestine Action is currently being challenged in the courts.)

Also last summer, a man named Hamit Coskun was fined £240 for a “religiously aggravated public order offence” after burning a Quran and shouting profanities against Islam outside the Turkish consulate in London. Meanwhile, a man who assaulted him with a knife during his protest was spared jail, with the judge noting that the man had felt “deeply offended” by Coskun’s actions.

Finally, five years after showing an image of the Prophet Muhammad during a religious studies class, a teacher in Batley, Yorkshire, remains in hiding due to threats from parents against him and his family. A 2024 independent review found that “the growing targeting of teachers and the teaching of controversial subjects beyond blasphemy is being increasingly viewed as too high risk.”

Unlike in the United States, free speech in the UK is not enshrined in a constitution, but has instead developed as a tradition, beginning in the 16th century and gradually expanding in the centuries since. In law, freedom of expression is protected under Article 10 of the 1998 Human Rights Act—though the key passage is dangerously ambiguous, allowing the government to restrict speech if they deem it necessary to prevent “disorder or crime” or protect “health or morals.”

To make matters worse, free speech in Britain is often seen as a right-wing issue, especially when it comes to the debate around women’s rights and transgender rights. The assumption that free speech is a right-wing cause is exacerbated by figures in the Trump administration calling attention to the erosion of free speech in the UK. (J.D. Vance, for example, has warned that Britain is going down a “dark path,” though his kind concern here is undermined by the numerous actions the Trump administration is itself taking against free speech in the United States.)

What the UK needs is to inspire a fundamental appreciation for free speech across the political spectrum. Too often, free speech is seen as a controversial value that only matters if you want to say something very, very bad. Instead, we need to champion our long history of celebrating free speech and use this to demonstrate why it’s so important.

This means that legislation such as the OSA must be repealed. While protecting children is important, introducing the concept of content that is legal but “harmful,” as well as requiring users to submit personal information to verify their age, creates a vague category that can be adjusted or amended depending on fluid definitions of harm.

Repealing the OSA would also let adults like me read potentially upsetting or angry Substack comments in peace—without having to provide evidence that we’re mature enough to handle it.

Leonora Barclay is Head of Podcasts at Persuasion.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

If the user already has a credit card linked to their account, this automatically verifies them.

Swimming is now illegal, but life jackets are required. We must all simply float helplessly amidst the information detritus: floating amidst information garbage, helplessly trusting Keir Starmer and his European censorship mafia. But if you lift an arm to swim away you will be jailed.

Watch the Mike Johnson speech to British Parlement. It was epic.