Gavin Newsom, You’re No Bill Clinton

Not even close.

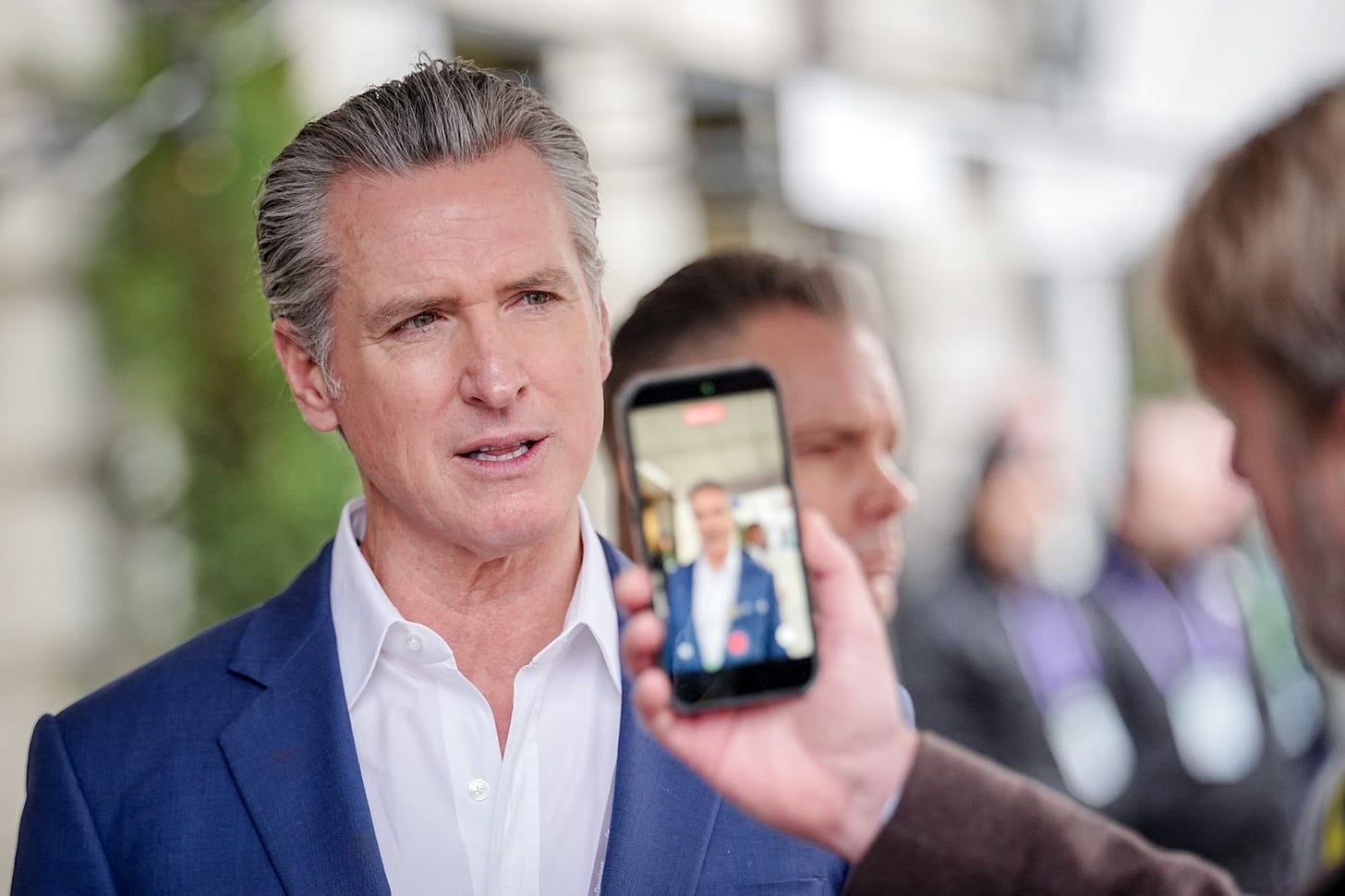

Gavin Newsom has had quite a year. While other Democratic politicians have struggled to adapt their pitches to the chaos of the second Trump term, Newsom has responded with a blizzard of activity that has dramatically raised his national profile. He has also benefited from copious, if not fawning, media coverage including a splashy recent profile in Vogue Magazine. At first mired in single digits with a scrum of other potential candidates, all trailing Kamala Harris by wide margins, he is now within striking distance of her in three commonly-cited poll averages of primary voter support for the 2028 Democratic presidential nomination.

His rising strength is reflected in the betting markets. On Predictit, he is far and away the betting favorite for the Democratic nomination, way ahead of AOC (second) and Harris (third). And in the market on the 2028 general election, he is way ahead of other Democrats and very close to the leading Republican candidate, JD Vance.

What accounts for this remarkable pro-Newsom surge? How did this liberal California Democrat win over so many in the wake of Democrats’ comprehensive defeat running… a liberal California Democrat?

The answer lies in Newsom’s ability to be everything to, well not everybody, but to every Democrat. Think of Gavin Newsom not as an ordinary politician but as a message delivery system—and a very effective one. Of course, all politicians to varying degrees are that. But Newsom stands out as letting absolutely nothing stand in the way—principles, beliefs, prior positions—of delivering the message he deems most politically effective at any given time to any given audience.

That has enabled him to appeal to diverse Democratic audiences. Think of Resistance liberals, whose white-hot anger at Trump is sure to galvanize a large share of Democratic primary voters. Right after Trump was elected, Newsom declared a special session of the California legislature. His office said:

The special session responds to the public statements and proposals put forward by President-elect Trump and his advisors, and actions taken during his first term in office—an agenda that could erode essential freedoms and individual rights, including women’s rights and LGBTQ+ rights … A special session allows for expedited action that will best protect California and its values from attacks.

A steady stream of denunciations of Trump administration actions from Newsom and the governor’s office has followed, especially during last June’s protests against ICE actions in Los Angeles which resulted in the deployment of the National Guard to quell riots. Newsom did not hold back his rhetoric or legal actions against this development. He said:

Democracy is under assault right before our eyes—the moment we’ve feared has arrived.

He’s taking a wrecking ball to our Founding Fathers’ historic project.

And so on. Indeed, Newsom has not missed a chance to aggressively oppose everything the Trump administration has done, whether it directly involves California or not. He has traveled to Brazil to oppose Trump’s climate policies at COP30 and, most recently, showed up at the World Economic Forum in Davos to denounce the administration. And, in reply to Republican attempts to gerrymander congressional seats in Texas and elsewhere, he has happily torn up nonpartisan districting in California to heavily gerrymander the state for the Democrats.

In essence, he has appointed himself Chairman of the anti-Trump Resistance and has the receipts to back it up. In Resistance liberal land, they love this just as Newsom intends.

But for those who are concerned that the party must moderate some, not just resist Trump, Newsom also has something to offer. He started a podcast, This is Gavin Newsom, where his guests have included the late Charlie Kirk, Steve Bannon, Ben Shapiro, and other conservative luminaries. This has provided him with the opportunity to venture some cautious signals that he is more moderate than the average Democrat. In his podcast with Kirk he agreed that the presence of trans-identified biological boys in girls’ sports seemed “unfair” to him. And in his recent podcast with Shapiro, he allowed as how calling ICE activities “state-sponsored terrorism” was not justified and that it was probably not a good idea to call for abolishing ICE. Related, in a conversation with Ezra Klein, he admitted that “we [the Democrats] failed on the border, we have to own that.” He has also, in his actions as California governor, responded to moderates’ concerns about homeless encampments by supporting moves to dismantle them and to concerns about crime with tougher rhetoric and additional tools to prosecute felonies and drug dealers.

On the other hand, he has not been shy about reassuring progressives and “woke” Democrats that he is still one of them. For example, after his podcast statement on trans-identifying boys in girls’ sports, he almost immediately walked back any implication that he would support a policy to change that situation in California or any other place. In his interview with Klein, he was quick to point out and defend the provision of health insurance to illegal immigrants as part of his overall commitment to universal health care. He refused to support a crime ballot measure, the prosecutor-backed Proposition 36, which reversed many provisions of the earlier Proposition 47 by classifying more crimes as felonies and increasing penalties (it passed overwhelmingly anyway). And of course, there’s his overall record as governor of California where he has supported one progressive priority after another from expanding Medicaid to undocumented immigrants to restricting police’s ability to enforce prostitution laws.

For economic populists, besides the usual railing against economic inequality, Newsom has been staunch in his support of higher minimum wages and more generous social welfare programs. He also succeeded in getting the earned income tax credit doubled. He is tight with California labor unions, including the umbrella California Federation of Labor Unions, the Service Employees International Union, and the California Teachers Association, all of whom enthusiastically support Newsom.

Even the emerging “abundance” faction of the Democrats gets the love from Newsom. He has supported key YIMBY initiatives, especially SB 79, which has eliminated long-standing regulatory obstacles to rapid development of dense housing near transit stations. More generally, he has ostentatiously declared himself to be in favor of an “abundance agenda” and has said that the seminal text of the abundance movement, Ezra Klein’s and Derek Thompson’s Abundance, “is one of the most important books Democrats can read.”

But in parallel with all these other commitments, Newsom is—and always has been—close to Big Tech. He has opposed, as his friends in that world demanded, the proposed wealth tax on California billionaires and has generally favored a light touch on regulating the industry, most recently on AI.

Finally for realpolitik Democrats, who don’t align with—or even care about—any of these factions but just want to beat Trump by any means necessary, Newsom also wants to be their guy. He is more than willing to fight dirty; no tactic can be ruled out if it is potentially effective. His social media team out of the governor’s office is now notorious for aping Trump’s unhinged, all-caps style and dishing out scatological insults. To paraphrase Michelle Obama, “when they go low, we go lower.” That warms the heart of super-partisan Democrats and consultants who just want to win.

Gavin Newsom: friend of the Resistance, friend of moderates, friend of progressives, friend of populists, friend of labor, friend of abundance-istas, special chum of Big Tech, and hard man for the Democratic Party. He’s got it all, twinned with a preternatural ability to deliver a perfectly calibrated message to each of these audiences when called upon to do so.

The Gavin Newsom message delivery system brings to mind another famed Democratic message delivery system, Bill Clinton, who was similarly adept at reaching a wide range of audiences and similarly willing to bend his principles to do so. Indeed, Newsom, in a fascinating profile of him written by Helen Lewis for The Atlantic, professes his admiration for Clinton and is clearly seeking to model much of his political strategy on The Man from Hope.

So is Newsom the next Bill Clinton? I don’t think so. Despite the similarities there is one huge and hugely important difference: Clinton’s message delivery magic was in the service ultimately of reaching a general election audience, not just a Democratic audience. But the latter is what Newsom is optimized for—he’s never had to run in competitive elections and beat Republicans. Indeed, he has actually underperformed relative to the Democratic lean of his own state, according to the rigorous “Deciding to Win” report. Not only that, his 10-point underperformance relative to expectations in his most recent election is the worst of 21 potential candidates tested by the report.

But he does know how to appeal to Democratic audiences—which is increasingly what more and more Democrats seem optimized for. This is great for individual candidates in blue states, cities, and districts but terrible for the Democratic Party as a whole. It encourages the party—and candidates like Newsom—to think their basic positions don’t have to change much and that their past record, commitments, and statements don’t matter.

This is wrong and egregiously so, as the “Deciding to Win” report definitively shows (and common sense would suggest). Your record and past positions matter a lot once you have to speak to a general electorate that doesn’t share the baseline assumptions of partisan Democrats. Just ask Kamala Harris.

Will Republicans want to dredge anything up from the pandemic response? How about $11.4 billion disbursed to illegal claimants, per a Los Angeles Times report, with another $19 billion claims under investigation for fraud? Maybe they’d like to choose housing as a line of attack? Under Newsom, California has spent $24 billion on homeless housing under a landmark initiative, with some housing units costing over $1 million, and all for homelessness to increase by about 30,000 during that time. Or perhaps the soup du jour will be the “rail fail”—the strange compromise in California where Newsom postponed a massive high-speed rail project while leaving a Central Valley spur that Newsom has admitted is a “train to nowhere.” Or perhaps the focus can be on his early support for marijuana decriminalization—an issue that is starting to result in a backlash. And, failing all that, how exactly are heartland voters going to respond to Newsom’s concerted attempt to phase out gas-powered cars, with the result that California has the highest gas prices in the country?

Never mind that Newsom, in his current abundance-embracing persona, has been a thoughtful analyst of why massive state spending programs so often tend to fail. That sort of nuance will tend to be lost on general election voters. A great deal of California’s very visible dysfunction occurred on his watch—or, more broadly, during the period when progressive policies he favored were ascendant—with the state widely associated with out-of-control homelessness and a breakdown in crime enforcement in major metropolitan areas as well as with famously high taxes that have not yielded commensurate gains in quality of life. By openly discussing—in the friendly confines of his podcast—some of the problems of exactly the progressive policies that he is mostly closely associated with, Newsom makes the lane of attack against himself only that much more obvious.

When he ran, Bill Clinton could avoid many of these sorts of issues because he had been governor of a conservative state and had inevitably tacked closer to the national median. Newsom, in 2028, won’t have that luxury. He’ll find himself in a pretzel trying to distance himself from policies that he either vigorously promoted or that occurred under his watch—exactly the same problem that we saw play out with Kamala Harris in 2024.

Could the Democrats be about to make the same mistake with Gavin Newsom? Absolutely, because he knows just how to talk to them. That’s too bad because what they really need is a Bill Clinton and Gavin Newsom, well, he’s no Bill Clinton.

Ruy Teixeira is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-founder and politics editor of the Substack newsletter, The Liberal Patriot.

A version of this article was originally published in The Liberal Patriot.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

So as one would expect from an American Enterprise Institute writer, the big problem is Newsome is not a moderate Republican. Got it.

Great post. Can Newsom win in 2028? By a slim margin, probably yes. But that would be the bigger problem because that's not what America needs. By 2028 things are going to be in shambles and America will be desperate for a unifier. And that's where a Shapiro or a Whitmer could come in.