The Unexpected Persistence of John Rawls

We walk in the garden of his ideas.

We’re delighted to feature this article as part of our new series on Liberal Virtues and Values.

That liberalism is under threat is now a cliché—yet this has done nothing to stem the global resurgence of illiberalism. Part of the problem is that liberalism is often considered too “thin” to win over the allegiance of citizens, and that liberals are too afraid of speaking in moral terms. Liberalism’s opponents, by contrast, speak to people’s passions and deepest moral sentiments.

This series, made possible with the generous support of the John Templeton Foundation, aims to change that narrative. In podcast conversations and long-form pieces, we’ll feature content making the case that liberalism has its own distinctive set of virtues and values that are capable not only of responding to the dissatisfaction that drives authoritarianism, but also of restoring faith in liberalism as an ideology worth believing in—and defending—on its own terms.

According to popular perception, universities have become cesspools of radical left-wing indoctrination, dominated by cultural Marxism, critical race theory, and post-modernism. As someone who has been working on the inside through the past three decades of intellectual fads and enthusiasms, I am sorry to report that, not only is this false, it is the opposite of true. The hegemonic ideology in the fields of political philosophy, legal theory, and political science, throughout my entire career, has been American liberalism. And not just any old American liberalism, but rather the very specific manifestation of this tradition articulated in the work of John Rawls.

Indeed, the intellectual dominance of Rawls has been so complete, for so long, that we have all become desperately bored of talking about him. To provide a sense of the magnitude of the phenomenon, consider that, of the five most highly-cited works of English-language political philosophy published in the past century, two were written by Rawls, and the other three were written in response to Rawls. Political philosophy has basically been all Rawls all the time for as long as I can remember. Every decade or so a new book comes along, promising to shift the paradigm, to give us all something new to talk about. Each one has fizzled out, sending us all back to Rawls.

What explains this extraordinary persistence? How could this unassuming, and in many respects naive, American philosopher have come to bestride the world like a colossus? This is what I shall attempt to explain.

Before getting to that, however, it is important to acknowledge some of the barriers to a proper appreciation of Rawls’ work. Many people have read a few chapters of Rawls but don’t really get why he is such a big deal. The problem is not that he wrote obscurely—his prose is perfectly ordinary, workaday English. He also used footnotes sparingly and spent very little time discussing the work of others, which makes his writing accessible even to those without much background. The major problem with his writing is that it is boring, and much of what he says seems self-evident. Because everything is so understated, it is easy to miss its importance.

Many readers have also been distracted by the fact that Rawls’ most well-known argument, about the “veil of ignorance” and the “difference principle,” doesn’t really work.1 In this respect, he is a bit like Immanuel Kant. Many readers have also had difficulty taking Kant’s work in moral philosophy seriously, because the argument for the “categorical imperative” that he supplies, in the second section of the Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, does not work either. But it is a terrible mistake to conclude from this that Kant had nothing interesting to say about morality, merely because his supreme principle of morality was wrong. What is important about Kant’s moral philosophy is the way he sets things up. It is his framing of the problem that revolutionized our thinking about morality, not the specific solution that he proposed.

The exact same thing is true of Rawls. Within my world of academic philosophy I’ve never met anyone who endorses the specific principle of justice that Rawls proposed. In order to understand the importance of his work, one must focus on the way that he frames the problems of modern liberalism, and of liberal political philosophy. (This is also why it is difficult to get a sense of Rawls’ importance from reading one of the many textbook introductions to his work, because these discussions tend to focus on the doctrinal elements of the view, which are the least defensible or interesting.)

Because Rawls was an American, in the better sense of the term, he starts out his most important book, A Theory of Justice, by stating, with perfect clarity and in plain English, precisely what he intends to do:

My aim is to present a conception of justice which generalizes and carries to a higher level of abstraction the familiar theory of the social contract as found, say, in Locke, Rousseau, and Kant. In order to do this, we are not to think of the original contract as one to enter a particular society or to set up a particular form of government. Rather, the guiding idea is that the principles of justice for the basic structure of society are the object of the original agreement.

This is the first and most important paradigm shift in Rawls’ view—but it’s easy to miss, because it’s expressed so simply. Classical 18th century social contract theory, which established the basic principles of liberalism, lacked generality, because it was only a theory about the state. It had nothing to say about the rest of society, other than that these domains should be free from state interference. This became an enormous weakness in the 19th century, with the progress of industrialization, urbanization, and proletarianization, because it meant that social contract theory had nothing to say about a very long list of growing social problems, including pretty much anything going on in the economy. This is why liberalism practically died out in the early 20th century—it had abdicated the field when it came to discussing the most pressing issues of the day.

Rawls’ strategy for reviving liberalism was to reconceptualize the social contract in a more abstract way. The familiar story that one finds in Locke or Rousseau, about an initial “state of nature” that people seek to escape by creating a sovereign power, should be considered a metaphor for an initial condition in which individuals are failing to cooperate with one another, and so seek to escape from these collective action problems by creating institutions. Society, from this perspective, should be considered a “cooperative venture for mutual advantage,” governed by a basic institutional structure, which includes, but is not limited to, the state. Most importantly, the economy—the system of property rights and exchange relations—is a part of this institutional structure.

There are many different ways to organize a system of cooperation. This creates a choice problem that cannot be resolved simply through appeal to the self-interest of participants. We require a set of principles to determine the specific modalities of cooperation. A theory of justice, in Rawls’ sense of the term, is basically just a set of such principles. The major obstacle to reaching agreement is that self-interested individuals will be inclined to make self-serving proposals, which will naturally be rejected by others. The best way to achieve agreement is therefore to neutralize this tendency, by imagining that individuals must choose principles without knowing what position they will eventually occupy in society. A theory of justice, Rawls suggests, should consist of principles that would be endorsed under such a constraint. Plausible candidates include not just the economist’s favorite principle, Pareto efficiency, but also a suitably formulated principle of equality.

This reconceptualization of social contract theory accomplishes several things. First, it offers an enormous demystification of the concept of justice. Rather than viewing these principles as handed down by God, or as grasped through intuitions that we cannot explain or defend, Rawls sees justice arising organically out of our efforts to piece together stable systems of cooperation. This makes our attempts to secure justice part and parcel of the history of the human social world. (To put the point somewhat more philosophically, his normative principles are tied to a specific social ontology.) One can see in the trajectory of human civilization an attempt to create more extensive, more robust systems of cooperation, accompanied by increasingly sophisticated efforts to articulate the principles of justice that structure the more successful of those institutions. Part of what gives Rawls’ view staying power is the fact that this broader picture is so compelling (and the fact that rival views lack any comparable picture).

The other, more obvious, accomplishment in Rawls’ view is that it corrects the greatest weakness of classical liberalism, because its principles apply to all of society and not just the state. As a result, the question of whether the economy should be organized along capitalist or socialist lines, or something in between, becomes something that can be intelligibly debated within a liberal framework. Indeed, the Rawlsian view allows one to pose, and answer, extremely fine-grained questions about the proper role of the state in the economy. Classical liberalism, by contrast, tended to favor laissez-faire capitalism by default, rather than for any affirmative reason, because it lacked a theory of justice that could be applied to the private sector. Thus Rawls’ work inaugurated a “hundred schools of thought” period within Western liberalism, as theorists explored the implications of the view in different domains.

A Theory of Justice attracted a great deal of attention, and a great deal of criticism, when it was published in 1971. At the time, Rawls was still treating questions of political philosophy (such as “what is justice?”) the same way that Plato did—as a set of intellectual puzzles that needed to be solved (such that, once we figure out what justice is, we can proceed to build a society that will embody the ideal). The problem that he immediately encountered was also as old as Plato. Having put forward his most clever argument in support of his favored conception of justice, he found that most people still disagreed, and insisted on defending their own quite different views.

This led to the second big move in Rawls’ work, which took the form of a curve ball that he threw everyone in his second book, Political Liberalism. Most philosophers, when they encounter objections to their arguments, double down on the original method, trying to come up with better arguments, with the hope that this will silence the critics and end all disagreement. Rawls, however, took a different tack. If one were to imagine his response to critics stated conversationally, it would go something like this:

I have given you my preferred conception of justice. You have given me yours. Evidently we disagree. Furthermore, there are people out there who disagree with us both, even more strenuously—consider, for example, orthodox followers of various religious traditions. Perhaps someday, someone will come up with an argument so persuasive that consensus on these questions will be reached. But in the meantime, and despite our disagreements, we are still in a position to engage in mutually beneficial cooperation. In order to establish such a system of cooperation, though, we will require some principles. We might choose to think of these as principles of justice. Naturally, because we are trying to organize a system of cooperation among individuals who disagree about fundamental questions of justice, those principles cannot presuppose the correctness of any one particular view. They must instead be freestanding with respect to all those positions.

Again, with his gift for understatement, Rawls suggested that we refer to a theory that is freestanding in this way as a “political” conception of justice (hence the title of the book). He then suggested that the theory of justice presented in his previous work be considered, not the correct answer to the age-old question “what is justice?”, but rather as a candidate for adoption as a political conception of justice. We can think of it as the theory we should use for now, while we debate the question of what the best theory (in some stronger sense of the term) might be.

Many philosophers found this argument disorienting. Rather than making a move in the familiar game of philosophical argumentation, Rawls was overturning the board, recommending that we play a very different game. Instead of trying to answer the traditional first-order questions about the best form of society, the nature of the good, or the meaning of life, he suggested instead that we focus on a second-order task, of finding principles that would be acceptable to people who disagree with one another about the correct answers to these first-order questions.

This approach provides a very different way of thinking about traditional liberal ideas such as individual rights. I might believe that the best life requires solitary contemplation, while you are committed to unbridled hedonism, and yet despite these differences, we can nevertheless agree that we should each have a bundle of rights that protects our ability to pursue these incompatible visions—not least because they protect us each from interference by the other. Instead of trying to resolve the deeper questions that divide us, Rawls suggested that we focus on the shallowest possible bases of agreement, in order to achieve what he called an “overlapping consensus.”

Seen in this light, it is easy to understand why the recent anti-liberal polemics of “common good conservatives,” like Adrian Vermeule or Patrick Deneen, have been met with a collective yawn from academic philosophers. After Rawls, it is impossible to see these views as any sort of a challenge to liberalism, because they make no effort to think politically about questions of justice. These theorists are still playing the old game, seemingly oblivious to how Rawls changed the terms of the discussion. And so the liberal response to these theorists, to the extent that one is required, would be something like this:

Congratulations, you have done a great job articulating your preferred conception of the good life! Your next step should be to persuade all of your fellow Christians of the correctness of Catholic doctrine on these points, after which you should get to work on persuading all of the atheists, Muslims, Hindus, etc. Once you have achieved consensus then we can start to build this ideal society. But in the meantime, we are going to need some principles to govern our institutions, since there are many opportunities for mutually beneficial cooperation among individuals who disagree about such questions. If you feel that you have something to contribute to this conversation, which is what the rest of us have been talking about, please don’t be shy.

Rawls, it should be noted, did not rule out the possibility that someday a moral genius might come along, able to articulate a vision of the good life so compelling that all of humanity would unite under the same banner. He grounded his commitment to political liberalism in what he called the “fact of pluralism,” in order to emphasize that reasonable disagreement about questions of the good life is, first and foremost, an empirical feature of the world that we live in, not a necessary one. At the same time, he did not think that this state of affairs was likely to change. He claimed rather that the exercise of human reason, under conditions of freedom and equality, would tend to produce more, not less, disagreement about the nature of the good life.

In other words, people of good will, confronted with the deeper questions of human existence, have a tendency to come up with different answers, without anyone necessarily making any errors of reasoning or judgment. The more freedom people have to consider and debate these questions, the greater the variety of answers they are likely to produce. Because of this, value pluralism should not be considered a passing phase, but rather the permanent condition of liberal democratic societies. The important point is that this sort of pluralism need not be a conversation-stopper when it comes to thinking about justice. A central objective of the liberal tradition, throughout its entire history, has been to find principles that can be defended without presupposing the correctness of any particular set of values.

These insights serve to explain why so many contemporary philosophers see the history of liberalism as divided between a pre- and post-Rawls era. Rawls is important not for the specific doctrines that he proposed, but rather for the general approach that he adopted toward the political questions facing modern societies. Of course, the revolution in liberal philosophy that he carried out brought its own difficulties. For example, unlike classical liberalism, modern liberalism is much more ambiguous in its understanding of both constitutional law and individual rights. Nor does it offer any easy answers to traditional questions about the role of electoral democracy in a liberal society. It cannot easily be extended to deal with questions of international law and global justice. Its application to minority rights, race relations, and family organization is contested. All of these weaknesses and ambiguities have elicited volumes of commentary and debate, which has been keeping political theorists busy for decades.

There is of course some irony in the fact that the great efflorescence of illiberalism that has been occurring in Western societies, contaminating both the left and the right, has been occurring at a time when liberal ideas enjoy unparallelled hegemony within the higher reaches of the academy. Although there has been some inclination to blame universities for corrupting the young, most of us who teach first-year courses will have observed that students are coming to us with already well-formed illiberal ideas, which we must challenge them to reconsider. I find myself now spending an entire lecture walking them through Rawls’ concept of “reasonable disagreement,” a topic that with previous generations merited no more than a five-minute summary.

Similarly, there is a real problem with human resources staff running amok at many universities, my own included, but it’s not because they’ve been listening to our lectures! Because if they listened to what we are teaching, they would discover that we’ve all been spending an inordinate amount of time obsessing over the seemingly milquetoast but curiously persuasive liberalism of John Rawls.

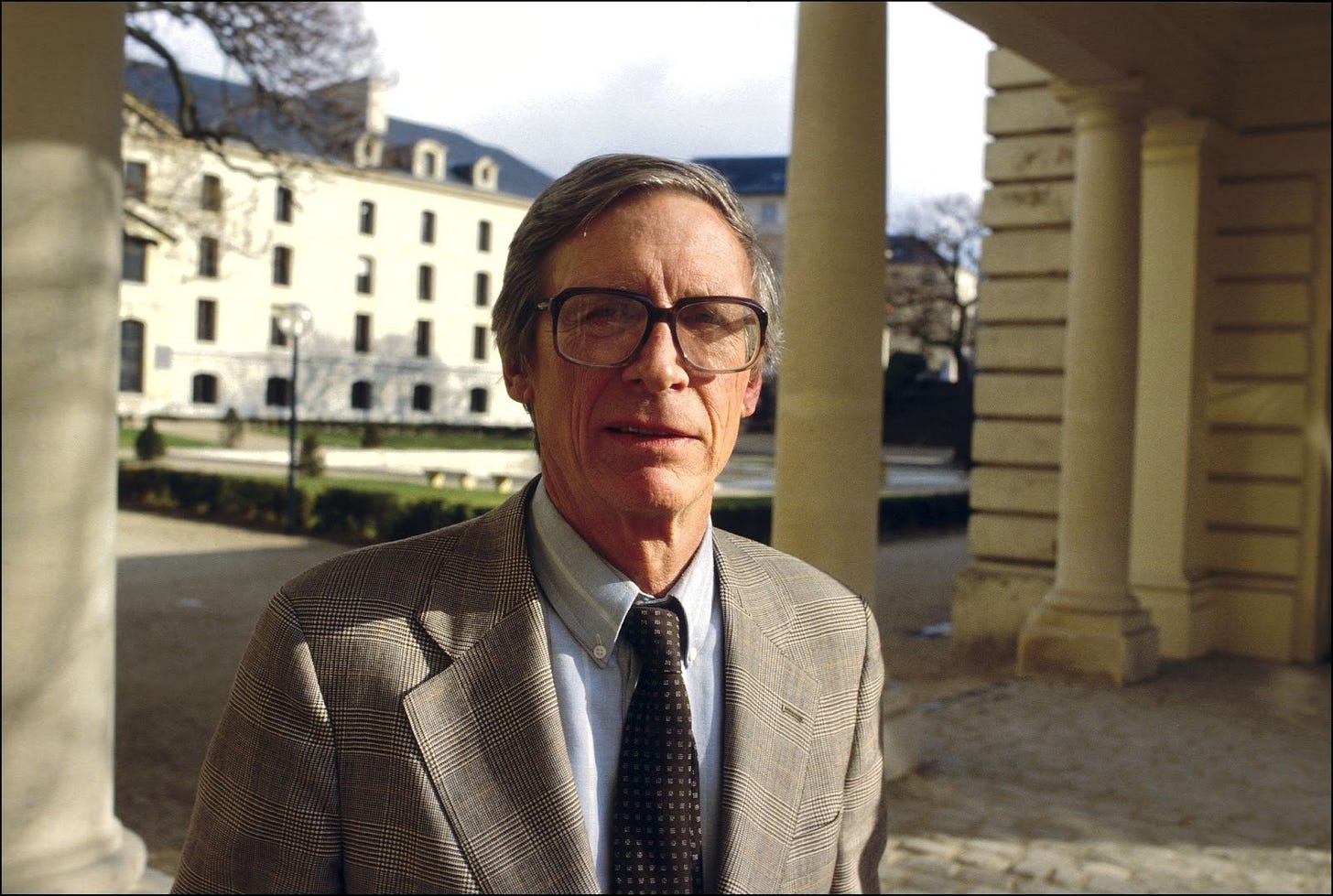

Joseph Heath is a Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Toronto and writes the Substack In Due Course.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

For those who are interested in the details: Rawls claims that if individuals were forced to choose principles of justice for society not knowing which social position they would wind up occupying (i.e. behind a “veil of ignorance”), they would select the arrangement that maximizes benefit to the worst-off person (i.e. the “difference principle”). Critics were quick to point out that, if these individuals engaged in ordinary probabilistic reasoning, they would choose instead the arrangement that maximizes average benefit. They would only choose the difference principle if they were unusually risk-averse or paranoid (i.e. if they expected to have their eventual position determined by their worst enemy).

I taught Rawls every semester for over 35 years. I got to the point where I would use an acronym to capture the very basic first principal also found in Catholic Social Teaching: MFOF. "Most F'd Over First!" The preferential option of the poor in less civil terms. There is an evolved biological truth here: There is no such thing as perfect altruism; all altruism is in some way reciprocal altruism. That is why Rawls will endure. I am a social creature; I speak a social language; I know myself in social terms. There is no private language. So there is no fully selfish act that does not occur in the society we need for our own survival and the survival of our kin. Only a fool would not realize at any moment you may be the Most F'd Over.